Jun 14 2017

A study published in the journal Cell on June 13 has found that a class of small molecules can successfully penetrate and darken human skin samples. The drug developed in the laboratory by researchers in Boston also generates protective tans in red-haired mice. Similar to humans, mice are more vulnerable to skin cancer when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The molecules stimulate the cells to produce more UV-absorbing pigments, however more preclinical tests need to be done before it is proven safe in humans.

The current study is a follow-up of an earlier study published in 2006 in Nature. The earlier study showed how the topical compound forskolin, could stimulate a cancer-protecting tan in red-haired mice without the need of UV radiation. However, the researchers soon found that forskolin could not get into human skin as humans are relatively hairless compared with mammals. To withstand a range of environmental threats, such as UV radiation, muddy water, and cold temperatures, human skin had to toughen up.

"Human skin is a very good barrier and is a formidable penetration challenge, therefore other topical approaches just did not work," says senior author David E. Fisher, the Chief of Dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School, who led the earlier studies involving forskolin. "But ten years later, we have come up with a solution. It's a different class of compounds, that work by targeting a different enzyme that converges on the same pathway that leads to pigmentation."

The breakthrough came when Fisher's group at Mass General collaborated with chemist Nathanael S. Gray, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. They designed a class of molecules that have several properties such as lower molecular weight and the ability to pass through lipids (greater lipid solubility) assisting human skin penetration. After testing numerous candidates, this class of molecules was found to be capable of darkening human skin by inhibiting the Salt Inducible Kinase (SIK) enzymes, whereby genes are stimulated that induce pigmentation.

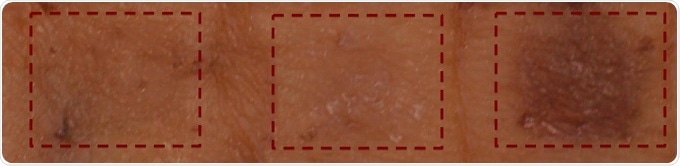

In the laboratory, the discarded extra skin was maintained on a Petri dish. When the researchers tested the small molecules on the skin sample, they found darkening that took place was proportional to the dose and the schedule at which the drug was applied. The red-haired mice could become almost jet black in a day or two when a sufficiently strong dose was applied. These artificially induced tans last for several days and the color fades away over time as normal skin cells slough off the surface. The skin tone gets back to normal within a weeks time.

Photograph shows the treatment of human breast skin explants with topical drug that induces pigmentation. Credit: Nisma Mujahid and David E. Fisher.

"We believe the potential importance of this work is towards a novel strategy for skin cancer prevention," Fisher says. "Skin is the most common organ in our bodies to be afflicted with cancer, and the majority of cases are thought to be associated with UV radiation. But we've found that the picture is more complicated, that red-blonde pigments are also more intrinsically carcinogenic, whereas dark melanin is intrinsically beneficial if not produced through use of dangerous UV injury to skin. Our approach could help switch pigments to those found in darker skin, without a need for UV exposure."

The long-term objective of this research is to create something that could be used in combination with traditional UV-absorbing sunscreens. The next step of the research team is to continue testing the safety of the small molecule in animals before doing toxicity studies in human beings.

Sources:

- https://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-06/cp-tdd060617.php

- http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(17)30684-8

- https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v443/n7109/full/nature05098.html