Dec 14 2017

Scientists of two new complementary studies researching mice and humans claim that they have the strongest evidence yet that memory T cells responsible for long-term immune protection also serve an additional role.

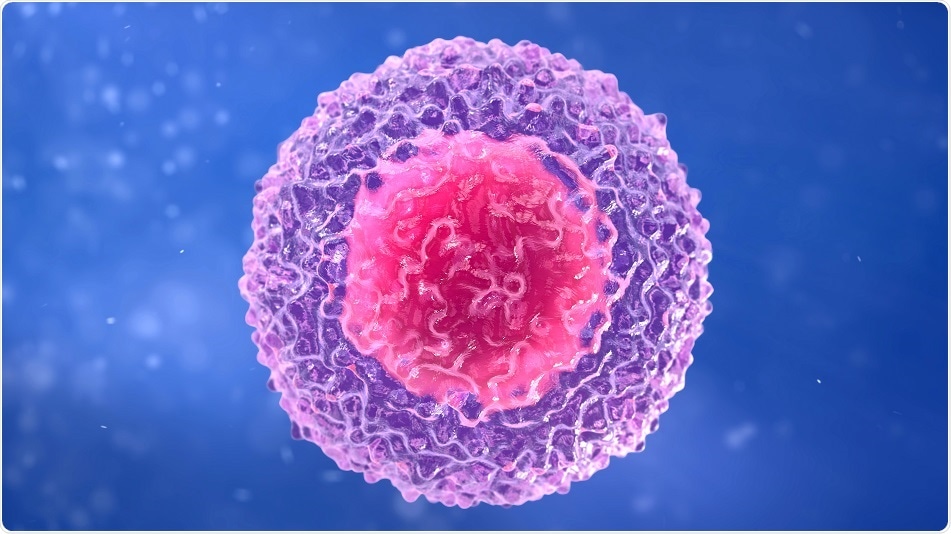

Credit: urfin/ Shutterstock.com

The studies conducted at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and the Emory University School of Medicine addressed a long-running debate on the origin of memory CD8 T cells, white blood cells essential to long-term immune protection. The findings are expected to aid scientists in designing more efficient vaccines and expanding cancer immunotherapies.

"This research provides the most compelling evidence yet that memory CD8 T cells arise from effector CD8 T cells and, in fact, must transit through an effector stage of differentiation before becoming memory cells."

Ben Youngblood, St. Jude Department of Immunology

In contrast to the effector CD8 T cells that fight cancer, viral infections, and other threats, memory CD8 T cells work like sentries, circulating around the body, ready to identify and rapidly respond if the virus or other threat reappears.

Previous studies indicate that effector and memory T cells develop as distinct lineages from naïve T cells. Naïve T cells can modify themselves in order to respond to novel viruses and other threats encountered by the immune system, as these cells are less differentiated.

The team led by Dr. Ben Youngblood worked on mice with a viral infection and demonstrated how memory CD8 T cells arise from a small subset of effector CD8 T cells. The findings of this study supported similar findings on human memory CD8 T cells in research led by scientists at the Emory University.

The study by Youngblood and team involved epigenetic and gene expression data and investigation of next-generation whole genome bisulfide sequencing that captures DNA methylation. According to them, as effector cells combating active infections, epigenetic traces of their time were retained by the memory CD8 T cells retained.

The researchers employed gene knockout, gene expression, and other methods to show that the effector cells that are transformed to memory CD8 T cells undergo demethylation, allowing the cells that are certain to become memory CD8 T cells to express genes related with naïve T cells as well as transformation from effector to memory T cells.

Researchers also indicated that the cells, even when transferred to another mouse, retained this capability. The demethylation, along with the methylation patterns of effector T cell that were retained by memory T cells, also left the memory CD8 T cells efficient enough to identify and rapidly respond to previously seen viruses and other threats.

The team further aims to use the study outcomes to analyze how to generate precision immunotherapies primed to recognize and attack tumors in patients. The findings are also expected to suggest possible strategies to enhance the effectiveness of vaccines.