Researchers at the Salk institute have found a way to manipulate the number of nuclear pores present in the perimeter of the nucleus.

Some cancerous cells have an increased number of nuclear pores and the current study could help researchers work out how to stop cancerous cells from multiplying out of control.

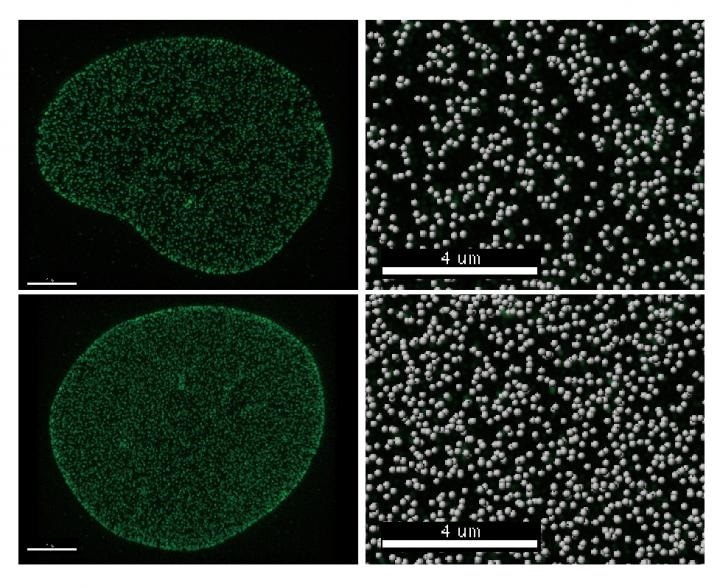

Cells with the Tpr protein (top row) have fewer nuclear pores than cells without the protein (bottom row). The right column shows a close-up of the pore density, with many more pores appearing in the absence of Tpr (bottom left). Credit: Salk Institute

"Previously, we didn't have the tools to artificially increase nuclear pores," says lead author Martin Hetzer. He adds that the study could provide a way of finding out what the consequences are of increasing the number of nuclear pores in a healthy cell to mimic those found in cancer cells.

Nuclear pores are transport channels that enable cellular material to be moved in and out of the nucleus and they mediate thousands of events per second. They are made from multiple copies of 30 proteins called nucleoporins.

As reported in the journal Genes and Development, Hetzer and team analysed the nucleoporin Tpr, which has been shown to be involved in some cancers.

The researchers found that each nuclear pore within a cell is unique and that each nucleus has a specific number of pores. The team then removed Tpr to see what effect this had on pore number.

Hetzer and colleagues were surprised to find that the number of nuclear pores dramatically increased.

Typically, when you 'knock down' or remove some of the proteins that make up the nuclear pore complex, the total number of nuclear pores goes down. Our surprising finding was that when we get rid of the nucleoporin Tpr, nuclear pore numbers went up dramatically,"

First author Asako McCloskey

Hetzer says this is the first time that modifying a component within the nuclear pore has resulted in an increased number of pores.

The finding suggests that Tpr is not only involved in transport but in controling the assembly of nuclear pores. The breakthrough could be crucial to researchers trying to manipulate the number of nuclear pores in their search for treatments.

Next, the team plans to use the approach to identify the effects of manipulating nuclear pore numbers in a range of cell types.