An interview with Dr. Anil Parwani, discusses how whole slide imaging of prostate cancer sections is helping to inform pathologists and improve patient outcomes.

Prostate cancer is often a devastating diagnosis for any patient to receive, please give an overview of the factors that contribute to the severity of the condition.

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men in the Western Hemisphere. It is more common in older men, but occasionally younger patients present with prostate cancer. Even at a younger age, the risk of cancer is not clear; we do not have a good understanding of how it progresses. Cancers that appear to have a similar morphology might behave differently between patients.

In some patients the cancer progresses very quickly, so we need a good risk assessment score to separate out these patients. When the cancer spreads to the bone and liver, the outcome for patients is poor. In a certain percentage of cases, the cancer is caught at a late stage, which can be devastating for patients.

What research do you and your lab conduct in prostate cancer? What are the end goals?

As a pathologist, my goal is to find good diagnostic assays that can help us stratify patients according to risk. We would like to find a model way of looking at a patient's cancer and its morphology to see if we can identify anything unique in that patient’s biopsy that can separate them out and be predictive of how they will progress and what their outcome will be. We would then like to be able to offer therapeutic options to the patient based on this.

How do you and your lab approach your research into prostate cancer?

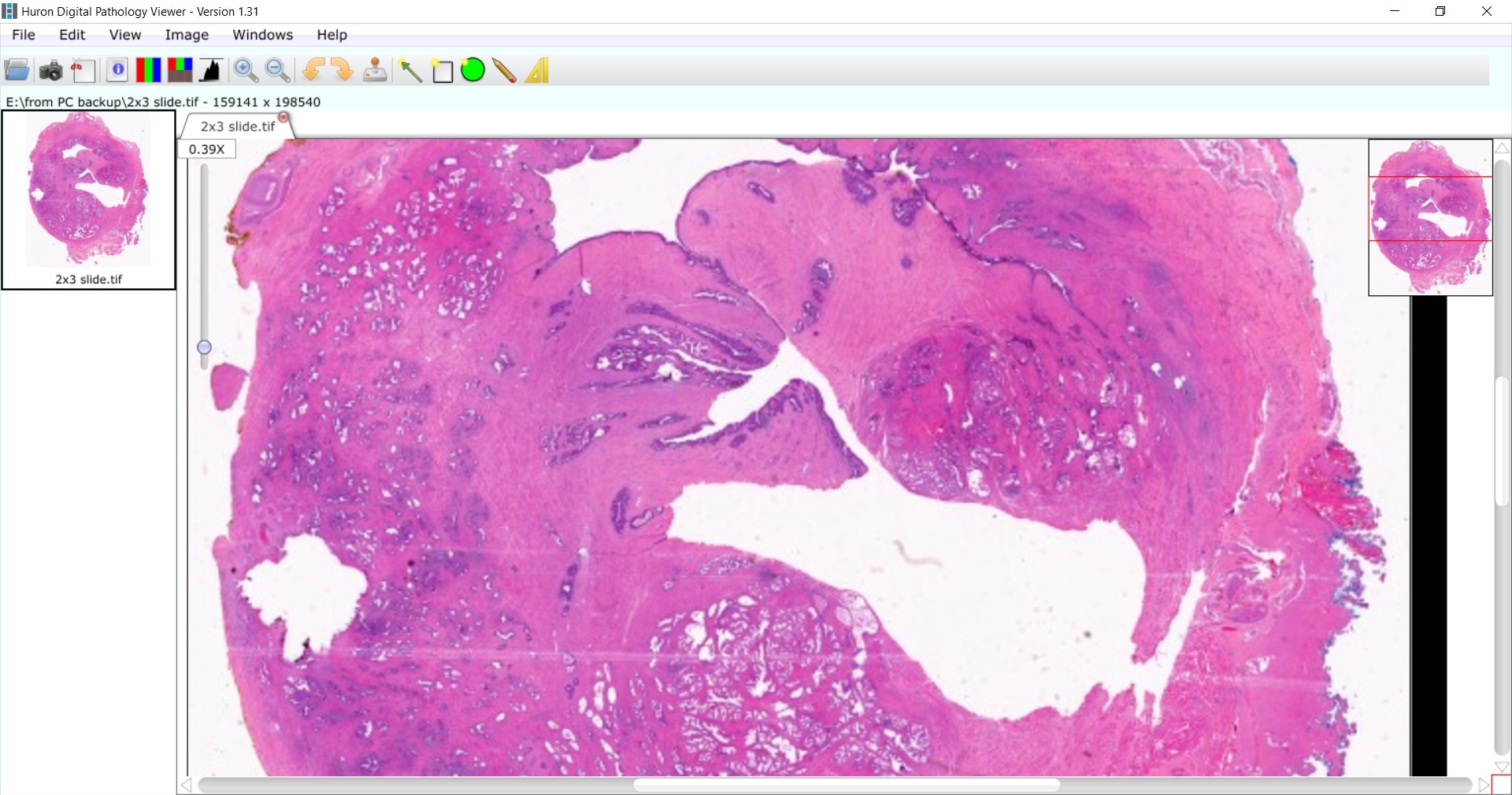

We have been assessing prostate cancer slides from patients for the last seven or eight years. We have been creating an image database of known prostate cancers and how the patients do. We have been looking at this retrospectively to see if we can understand patterns we can apply to the prostate cancer for a better future diagnosis.

Image credit: Huron Digital Pathology.

Our goal is to find better predictors of outcomes, such as the microenvironment of the cancer, how the cancer is growing in the stroma or what surrounds the prostate cancer cells. We would like to see if there are any unique signatures that we can decipher in this digital image.

Also, within a prostate biopsy, there might be benign mimickers of cancer, which can lead to misdiagnosis of cancer and overtreatment. We would like to find diagnostic features in the digitized slide that will help us separate the benign mimickers from variants of prostate cancer.

At the Digital Pathology Scanning Center, we have scanned over 800,000 slides over the last year and about ten percent of those are prostate cancer slides. We are creating one of the largest databases of prostate cancer tissues and the goal is to use this incredible resource to answer many of these questions.

What are the challenges associated with scaling up the digital pathology to such a large scale?

One challenge is being able to get a glass slide that is produced in the lab and convert that into a digital image. It requires a lot of streamlining and standardization of the processes. People have been scanning slides for many years, but when you start to do it on a large scale in a clinical lab, you have to pay very careful attention to detail and the standardization of the processes.

You have to follow rules and regulations, because these are patient materials. When these materials are digitized, and images are produced, we want to make sure that the image is a replica of the glass slide. We have to validate that process. We have to look at a glass slide diagnosis, compare it to a digital diagnosis and make sure that they are no different.

We also need to have downtime processes to cater for if the system goes down. Being able to function in a clinical setting requires teamwork. Just one or two people in the pathology department could not do it. We have to start working with multiple outside stakeholders, the IT department, the financial department, for example, which requires an incredible effort.

What are the unique challenges to standardizing workflows and scanning large prostate sections?

In our institute, we perform full-mount processing of prostate slides. When a patient has a biopsy, they are processed in the standard way to produce a standard slide. For the full mounts, we take the whole prostate. We ink it, fix it and then then obtain many sections of the whole tissue.

We put those into a large cassette that is processed, and paraffin blocks are made. From those paraffin blocks we make very thin, unstained slides which are then stained with H&E. One of the challenges that is unique to scanning such large slides is the need for special equipment. You need special scanners; not every whole slide imaging scanner can accommodate these large slides.

How has the TissueScope LE 120 affected the digital pathology lab at The James Cancer Hospital? What are the advantages and limitations?

The TissueScope scanner is optimized for whole mount slides, but it can also accommodate standard-sized slides as well. We like it because we are required to place whole mount tissue in special 2 by 3 slides and this scanner enables us to do that.

It enables us to mix and match to use standard slides, full mounts and it is even capable of scanning a slide up to 6 by 8, which is a very unique feature of the system. We can accommodate a large, high-throughput scanning workflow, all whilst maintaining good image quality. It is a very versatile, easy-to-use system that can scan a standard slide in less than a minute.

Image credit: Huron Digital Pathology.

How important is the reliability of the tissue scanner and the image quality of the samples that are produced?

It is extremely important, you want a system that can be optimized for your workflow, with an image quality that replicates the original sample and one that is reliable in performance and throughput. Image calibration and scanning need to be consistently high quality and you want to know you can walk away without issues.

The TissueScope, along with the other systems in our lab, allows us to continuously scan slides, without any interruptions. This system also has z-stacking capabilities, which is something other systems do not have.

The image quality is also really good, the images are very sharp, clear and crisp. We are at the stage of assessing image quality and validating this for clinical use now. We are looking at glass slide diagnosis in 60 cases and after a washout period of two weeks, pathologists will make a diagnosis based on the images taken and we will compare that to the original glass slide diagnosis.

What does the future hold for your research?

The key thing for the future is to continue scanning high quality images from patients with prostate and other cancers so we can start interrogating them for specific features such as stromal inflammation and the microenvironment of the tumor.

It is a case of continuing to get the image set more annotated and more curated, as well as continuing to obtain follow-up data on these patients because that is how we are going to build image-based signatures for patient stratification and find diagnostic clues that will distinguish between benign mimickers and variants of cancer.

We need to continue this journey of understanding pathology, patterns and how this applies to the grading, diagnosis and outcome of these patients.

What do you see as the future of digital pathology and how it will affect your work and the work of others in your field?

I think the future of digital pathology is very bright in terms of how far we have come from taking one hour to scan a slide to today, where systems can take less than a minute to scan a slide. Those slides can then be made available to experts worldwide for a second opinion, for example, and, to researchers for analysis and the development of deep learning algorithms.

It will not be long before more labs start to digitize their slides, and this will become the standard way of making a diagnosis in pathology. In the future there will be no "digital pathology," – it will just be a standard part of pathology and the pathology lab.

Where can readers find more information?

About Dr. Anil Parwani, M.D., PhD, MBA

Professor of Pathology and Biomedical Informatics

The Ohio State University

Anil Parwani is a Professor of Pathology and Biomedical Informatics at The Ohio State University. He also serves as the Director of Division of Pathology Informatics and Digital Pathology, Department of Pathology. Dr. Parwani has sub-speciality training in Genitourinary Pathology.

His pathology practice is focused in GU and he has research interests in benign mimickers and unusual variants of prostate carcinoma, diagnostic and prognostic markers in GU pathology, and molecular classification of renal cell carcinoma and bladder carcinoma.

Dr. Parwani has expertise in the area of Anatomical Pathology Informatics including design of quality assurance tools, tissue banking informatics, clinical and research data integration and mining, synoptic reporting in anatomical pathology, clinical applications of whole slide imaging, digital imaging, telepathology, image analysis and lab automation and workflow processes such as barcoding and voice recognition.

Dr. Parwani has published extensively and has authored over 300 peer-reviewed articles in major scientific journals as well as numerous book chapters and is also the editor of several books. He currently serves as an editor-in-chief of Journal of Pathology Informatics and Diagnostic Pathology.