Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine have managed to refine a stem-cell based approach to treating diabetes that improves how recipients respond to fluctuating glucose levels in the blood.

Nixx Photography | Shutterstock

Nixx Photography | Shutterstock

Scientists have previously worked with stem cells to transform them into insulin-producing beta cells, but until now, they have had difficulty controlling how much insulin the resulting cells produce.

Now, principal investigator Jeffrey Millman and colleagues have tweaked the “recipe” for producing these beta cells and made them more effective.

When the newly developed cells were transplanted into mice incapable of producing insulin, the cells started secreting insulin within just a few days and continued to control blood sugar effectively for months.

We've been able to overcome a major weakness in the way these cells previously had been developed. The new insulin-producing cells react more quickly and appropriately when they encounter glucose. The cells behave much more like beta cells in people who don't have diabetes."

Jeffrey Millman, Principal Investigator

Millman had previously been involved in a study where skin cells from a diabetes patient were converted into stem cells and then treated with a combination of factors to turn them into insulin-secreting beta cells.

The resulting cells, however, were not as effective as the researchers had hoped. Although they secreted insulin in response to glucose, they acted more like re hydrants, either making a lot of insulin or none at all, explains Millman: "The new cells are more sensitive and secrete insulin that better corresponds to the glucose levels."

As recently reported in the journal Stem Cell Reports, Millman and team made various changes to the “recipe” used when growing the insulin-producing beta cells from human stem cells.

They applied different factors to the cells at different times as they developed, to help them mature and to improve their function. The new cells were then transplanted into diabetic mice that had their immune systems supressed to prevent transplant rejection.

The insulin-producing cells were able to control blood glucose effectively. They essentially cured the diabetes for a period of several months, which was generally the duration of the animals’ lifespan.

Millman is uncertain of when the new approach may be ready for testing in human trials, but he thinks there are at least two approaches that could be assessed in people.

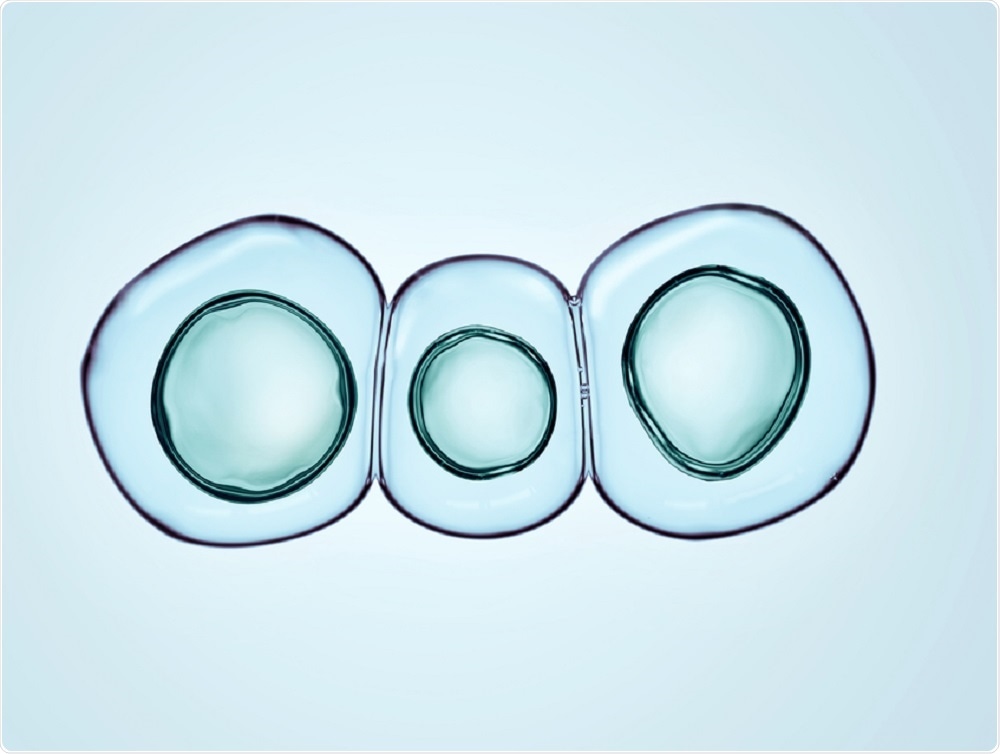

One would be encapsulating the cells in something like a gel with pores small enough to prevent immune cells entering but large enough to let insulin out, he suggests.

"Another idea would be to use gene-editing tools to alter the genes of beta cells in ways that would allow them to 'hide' from the immune system after implantation."

If the approach is proved to be safe and effective for people with diabetes, manufacture could be ramped up to the industrial scale, says Millman. His team have already grown more than a billion of the stem cell-derived beta cells in no more than a few weeks.