Feb 1 2019

Take a whiff when it rains after a dry spell, and breathe in the earthy scent that pervades the air. That smell comes from decomposing bacteria, and scientists call the compound geosmin.

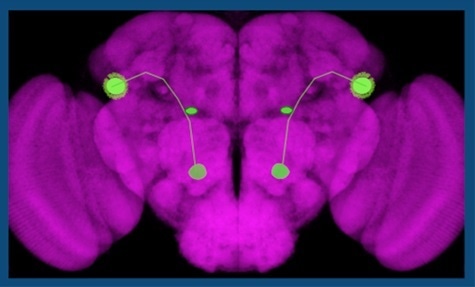

The green shows neural circuits controlling the sense of smell in the brain of a common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Credit: Chris Potter

Now, as reported in a paper published last summer in Cell, a team of researchers led by Chris Potter, Ph.D., an associate professor of neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, has used geosmin to create a new genetic technique in flies that could allow scientists to more accurately investigate how smell affects behavior.

They call the technique “olfactogenetics.” It works on the same principle as another popular neuroscience technique to genetically engineer specific neurons to fire off signals when hit by light. But instead of light, olfactogenetics uses geosmin.

Most odors are detected by multiple types of smell-sensing neurons, but geosmin is detected by only one type of neuron. That makes it easier for the researchers to program groups of neurons with the genetic code for sensing geosmin, while disabling it in those that already have the capability to detect geosmin. This way, when they release geosmin into the air, they can track which neurons are detecting the compound.

Because olfactogenetics uses an odor — not light — it allows the researchers to see how these neurons would normally function when sensing a smell, and it doesn’t run the risk of overstimulation.