A study of humans and monkeys published in JNeurosci has found the same subset of neurons encode actual and illusionary motion, although it takes the brain slightly longer to distinguish between the two. This finding supports, at the level of single neurons, what the Czech scientist Jan Purkinje surmised 150 years ago: “Illusions contain visual truth.”

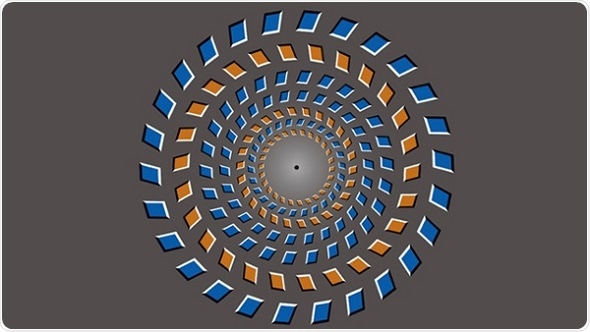

The Pinna-Brelstaff figure is a static image of rings that appear to rotate clockwise as one moves toward and counterclockwise as one moves away from the center.

Having previously identified the part of the human brain that responds to the Pinna illusion, Yong Gu, Wei Wang, and colleagues first confirmed that rhesus male rhesus macaques likely perceive the illusion similarly to people. The researchers then recorded activity from neurons in the previously identified brain regions and found these cells represent the illusionary motion as if it were real. A delay of about 15 milliseconds enables the brain to register the difference between actual and real motion. This study provides new insight into how the brain grapples with the mismatch between perception and reality.