The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has reportedly led to a reduction in cancer-causing HPV prevalence, but uptake of the vaccination has been slow, despite the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The CDC has been recommending that boys and girls up to the age of 15 receive the vaccine since 2006. However, it has now been shown that vaccination rates in populations at high-risk of contracting HIV are particularly low, increasing the risk of HPV and HIV co-infection.

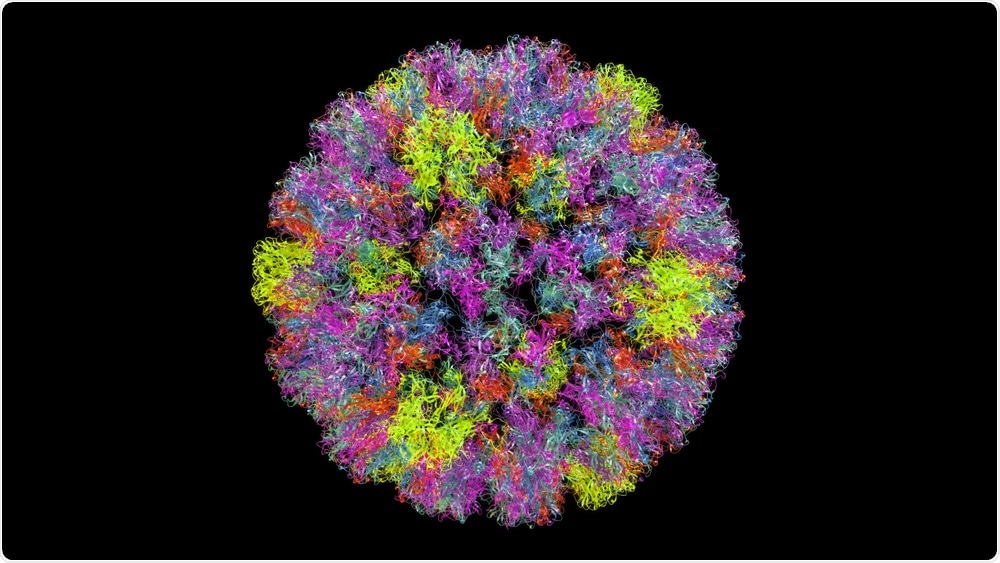

Yabusaka | Shutterstock

Yabusaka | Shutterstock

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the name for over 100 different types of common viruses. In most people, HPV does not cause any problems and are cleared by the body within two years, but some strains of the virus can cause genital warts or cancer.

Any skin-to-skin contact in the genital area, vaginal, anal, or oral sex, or sharing sex toys, can lead to the spread of HPV. As HPV does not present any symptoms, it is hard to know when it has been spread to another person.

The cancers associated with high-risk HPV are cervical cancer, anal cancer, cancer of the penis, vulval cancer, vaginal cancer, and some types of head and neck cancer.

In the UK, women are offered cervical screenings from ages 25 to 64 to test cervical cells for the presence of HPV to protect them against cervical cancer.

Men who are at a higher risk of anal cancer through anal intercourse can also be offered anal screenings in certain sexual health clinics.

But, according to results from a study presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2019, adults who have a high risk of contracting HIV were less likely to have received the human papillomavirus vaccine when compared to the general population, which may increase their risk of an HPV-HIV co-infection.

Lisa T. Wigfall, PhD, MCHES, from Texas A&M University in College Station, led the study and said that increasing the rates of vaccination in high-risk populations would include the “wide adoption of routine HIV testing for all adolescents and adults, regardless of perceived risk.”

Researchers presenting these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2019 used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (BRFSS) of 2016, which documented vaccination rates in individuals who had engaged in high-risk activities in the year before the survey.

The results were ‘alarming’

Out of 486,303 adults who participated in the survey, 16,507 (3.4%) had engaged in high-risk sexual activities or intravenous drug use. The rates of vaccination were very low in the group of 416 people who had complete data, and vaccination rates were extremely low in non-Hispanic black survey respondents.

Considering the “disproportionate burden of HIV/AIDs among this minority group,” Wigfall said, “it was alarming that almost all non-Hispanic blacks in the study were unvaccinated.”

Other statistics showed that 26% of gay/bisexual men between 18-33 years did start the three-dose course of the HPV vaccine, but only 6.2% completed the course.

In women, one quarter of high-risk heterosexuals aged between 18-36 finished the three-dose course of the HPV series, but no transgender men, women, or gender-nonconforming individuals had started the HPV vaccination series at all.

A lack of information may be to blame

There are concerns that these low vaccination rates leave HIV-positive people more vulnerable to anal and cervical cancer, as HIV significantly compromises the immune system, impairing its ability to fight off HPV infection.

Previous research published in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention suggested that patient uptake of the HPV vaccine can be influenced by how physicians talk about the vaccine, especially to parents of adolescents.

Lack of information, a belief that the vaccination is unnecessary or unsafe, or not receiving strong recommendations from their doctor all held parents back from vaccinating their children against HPV.

Each of these concerns can be addressed by talking with a provider. […] This finding really highlights the important role that parent-provider communication can play in increasing HPV vaccination.”

Teri L. Malo, PhD, MPH

Wigfall believes that communication between doctors and patients about the HPV vaccine should be reinforced in high-risk populations, from HIV-positive men and women, to HIV-negative gay/bisexual men and transgender men and women.

She believes that physicians may not have considered the connections between high-risk sexual behaviors in these groups with HIV and HPV co-infection.

“Gender and sexual orientation are important topics that should preclude us from identifying and targeting HPV vaccination efforts among high-risk populations,” Wigfall said.

The future looks bright

In Northern Ireland, boys aged 12 to 13 years old will be offered the HPV vaccine to protect them against the cancers associated with HPV, which will bring it in line with the rest of the UK.

The researchers conclude:

We can now look forward to a future where we can be even more confident that we will reduce cervical cancer and other HPV related cancers that affect both men and women.

This is an effective vaccine against a particularly harmful virus. I would encourage all parents to take up this offer and ensure their boys and girls are vaccinated.”