A particularly aggressive, metastasizing form of cancer, HER2-positive breast cancer, may be treated with nanoscopic particles “imprinted” with specific binding sites for the receptor molecule HER2. As reported by Chinese researchers in the journal Angewandte Chemie, the selective binding of the nanoparticles to HER2 significantly inhibits multiplication of the tumor cells.

© Wiley-VCH

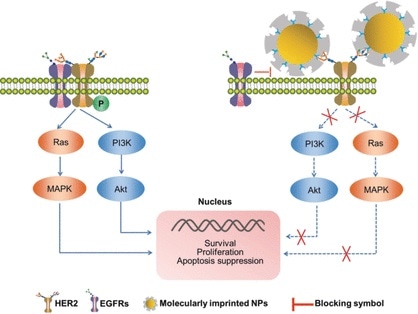

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women and one of the leading causes of death. About 20 to 30 % of breast cancer cases involve the very poorly treatable HER2-positive variety. HER2 stands for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2, a protein that recognizes and binds to a specific growth factor. HER2 spans across the cell membrane: one part protrudes into the interior of the cell; the other is on the cell surface. As soon as a growth factor docks, the extracellular parts of HER2 bind into a heterodimer with a second, closely related HER, such as HER1 or HER3.

This triggers a multistep signal cascade within the cell, which is critically involved in processes like cell division, metastasis, and the formation of blood vessels that supply the tumor. HER2-positive tumor cells contain significantly higher concentrations of HER2. One current therapy for early-stage HER2-positive tumors is based on binding an antibody to HER2 to block the dimerization. Researchers led by Zhen Liu at Nanjing University (China) have now developed “molecularly imprinted” biocompatible polymer nanoparticles that recognize HER2 just as specifically as an antibody in order to prevent the dimerization.

Nanoparticles can be molecularly imprinted in that – to simplify – a polymerizable mixture is polymerized into nanospheres in the presence of the (bio)molecules they are supposed to recognize later. The (bio)molecules act as a kind of stamp, leaving nanoscopic “imprints” in the spheres. These then perfectly fit the molecules they were imprinted with and bind to them specifically. In contrast to antibodies, the nanospheres are easy and inexpensive to produce and are chemically stable.

For the imprinting process, the researchers use a special method (boronate affinity controllable oriented surface imprinting) that is particularly controllable and makes it possible to imprint using chains of sugar building blocks (glycans) as templates. Many proteins contain specific “sugar chains”. These are unique, like a protein fingerprint. The researchers used this kind of glycan from the extracellular end of the HER2 proteins as their “stamp”. This allowed them to produce imprinted nanoparticles that specifically recognize HER2 and selectively bind to it, inhibiting the dimerization. They were thus able to significantly reduce the multiplication of tumor cells in vitro and the growth of tumors in mice. In contrast, healthy cells were essentially unaffected.

Source:

Journal reference:

Liu, Z. et al. (2019) Inhibition of HER2‐Positive Breast Cancer Growth by Blocking the HER2 Signaling Pathway with HER2‐Glycan‐Imprinted Nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. doi.org/10.1002/anie.201904860.