Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, have found that with age the neurons or nerve cells fail to perform an activity that they could when they were younger. The team explains that normal cells take out protein and other “trash” or “garbage” through a process of autophagy. This rids the cell of the dysfunctional proteins and aggregates of unused proteins.

As the cells age, this mechanism fails and since the nerve cells do not replicate, the proteins tend to build up within them. This could raise the risk of development of neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's disease, write the researchers. The study appeared in the latest issue of eLife and is titled, “Expression of WIPI2B counteracts age-related decline in autophagosome biogenesis in neurons.”

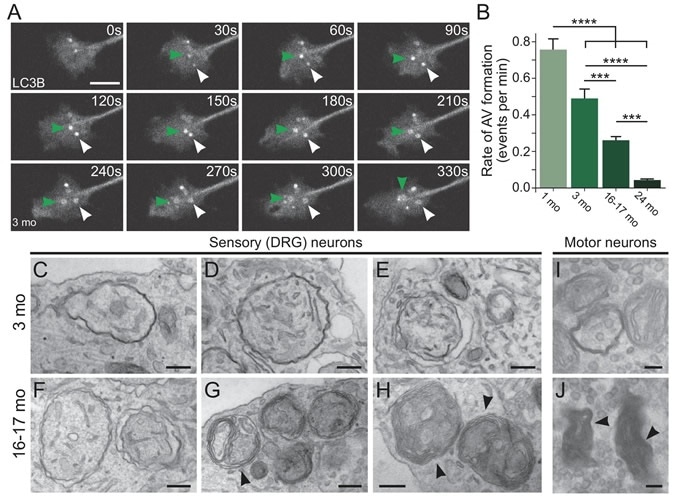

Aberrantly formed autophagosomes accumulate in neuron of an aged mouse (Credit: Andrea Stavoe, Penn Medicine; eLife)

The team used live-cell imaging or “dual labeling of autophagosome biogenesis” of neurons taken from young and old mice. The lead authors Erika Holzbaur, PhD, a professor of Physiology, and Andrea Stavoe, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Holzbaur's lab, explain that the process of autophagy in clearing the cells of the protein debris was a 2016 discovery that has won its discoverers a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2016. Co-researchers on the study were Pallavi Gopal from Yale University, and Andrea Gubas and Sharon Tooze, from The Francis Crick Institute, London.

The team wrote, “Young neurons appear to clear dysfunctional organelles and protein aggregates very efficiently but few studies have examined autophagy in aged neurons. Since age is the most relevant shared risk factor in neurodegenerative disease elucidating how autophagy changes in neurons with age is crucial to understanding neurodegenerative diseases.” Holzbaur said, “The current thinking among scientists is that a decline in autophagy makes neurons more vulnerable to genetic or environmental risks. What motivates our line of research is that most neurodegenerative diseases in which a deterioration of autophagy has been implicated, such as ALS, and Alzheimer's, Huntington's and Parkinson's diseases, are also disorders of aging.”

The researchers wrote that the process of autophagy (auto – self; phagy – eating) begins with the development of an autophagosome within the cell. This autophagosome eats up with damaged structural proteins, misfolded proteins that would not be used by the cell and structures that are to be demolished and degraded. These protein trash are then sequestered into the “biological trash bag”, until the autophagosome fuses with the lysomome within the cell. The lysosome contains enzymes that are powerful and can break down the protein and other garbage and also recycle material that could be reused. Thus the cell is cleared of the debris. The team writes, “Autophagosome biogenesis, conserved from yeast to humans, involves over 30 proteins that act in distinct protein complexes to engulf either bulk cytoplasm or specific cargo within a double-membrane.”

In the event of this process failing, there is accumulation of the trash within the cells and this can kill the neurons or nerve cells eventually, explain the researchers. Stavoe said, “Think city streets during a sanitation workers strike.”

In their study the team assessed the mouse neurons during the aging process. They noted that with age there was a significant decrease in the production of the autophagosomes. The autophagosomes that were produced in the aged neurons also had prominent defects, they noted. These decreased number and misshapen autophagosomes led to the accumulation of the protein debris within the mice neurons. Stavoe added that donor brains have shown that people with neurodegenerative disorders have similar misshapen fewer number of autophagosomes.

The researchers noted that one of the proteins called the WIPI2B in aged mice when turned on, could help the aged mice to produce adequate number of autophagosomes. This means that the whole process of taking out the protein garbage comes back on track, wrote the researchers. The team focussed on activation of this protein and add that this could help biologically regulate autophagosome formation. Stavoe said, “This stunning and complete rescue of autophagy using one protein suggests a novel therapeutic target for age-associated neurodegeneration.” To prove their point, the team then took out the WIPI2B protein from the young neurons and noted that this stopped the formation of the autophagosomes.

The authors concluded, “Ultimately, we showed that the rate of autophagosome biogenesis decreased in neurons during aging, but we mitigated this decrease by overexpressing a single autophagy component, WIPI2B.”

The study was funded by the NIH Pathways to Independence Fellowship and a Javits Award from NINDS.

Journal reference:

Andrea KH Stavoe, Pallavi P Gopal, Andrea Gubas, Sharon A Tooze, Erika LF Holzbaur, Expression of WIPI2B counteracts age-related decline in autophagosome biogenesis in neurons, eLife 2019;8:e44219 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.44219, https://elifesciences.org/articles/44219