Long-lived communities eat plants rich in natural compounds that may slow aging—now scientists are uncovering how these polyphenols work at the cellular level and why they might be key to a longer, healthier life.

Review: Dietary polyphenols as geroprotective compounds: From Blue Zones to hallmarks of ageing. Image Credit Zaporizhzhia vector / Shutterstock

Review: Dietary polyphenols as geroprotective compounds: From Blue Zones to hallmarks of ageing. Image Credit Zaporizhzhia vector / Shutterstock

In a recent review article in the journal Ageing Research Reviews, researchers assessed how polyphenol-rich foods commonly eaten in ‘Blue Zones’ by long-lived people might act as geroprotective agents to support healthy aging and prevent age-related diseases.

Current research indicates that polyphenols could modify key biological processes, thus protecting against aging. However, the research team stressed that further studies are needed to understand how polyphenols modulate the hallmarks of aging and promote longevity.

Aging Populations Must Stay Healthy Longer

Life expectancies are increasing worldwide as living conditions, medical technology, nutrition, and public health improve. This has highlighted the importance of ‘healthspans’ so people can remain healthy for longer and enjoy their improved lifespans.

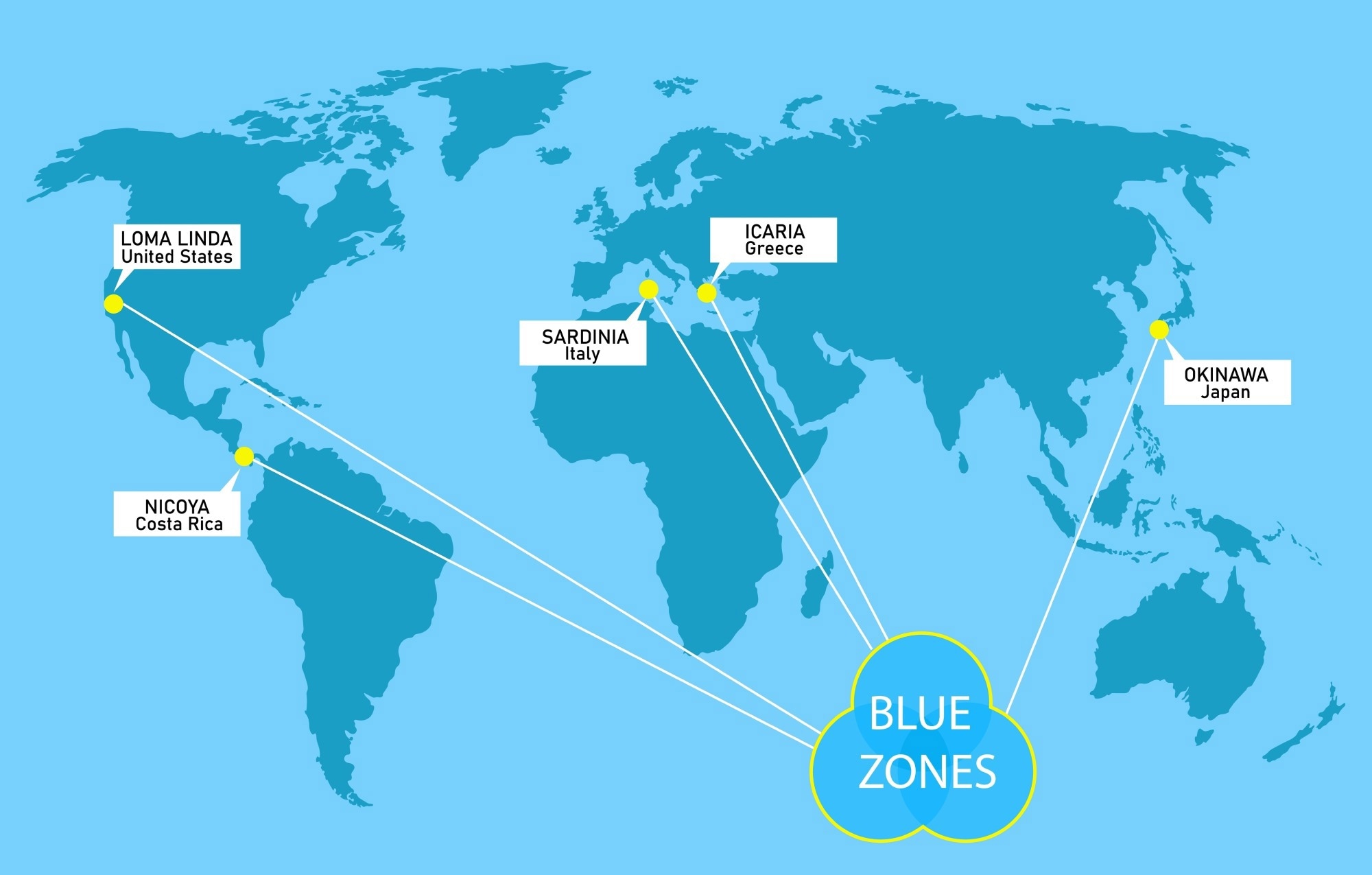

Researchers have turned to centenarians, or people who live past the age of 100, to glean valuable insights into what factors support such uncommon longevity. They have identified five Blue Zones, located in Loma Linda (California, United States), Sardinia (Italy), Okinawa (Japan), Nicoya (Costa Rica), and Ikaria (Greece), as places that have a disproportionate number of long-lived individuals.

Diet could be a key factor in promoting longevity, and one that is modifiable. Healthy diets are often rich in plant-based foods with high levels of polyphenols, which are plant compounds with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and may reduce the risk of heart disease, blood pressure, and high blood sugar. Thus, polyphenols could slow aging and reduce diseases that often come with age.

However, the authors highlight that polyphenol bioavailability is influenced by gut microbiota, food matrices, chemical structure, and individual metabolism—posing a challenge to estimating intake and efficacy. While the diets of people in Blue Zones are known to be rich in plant-based foods, exact consumption levels are not known.

Diet and Longevity in Blue Zones

In Okinawa, traditional nutrient-rich diets have been linked to lower rates of diabetes, dementia, and cardiovascular disease. Key components of diets in this Blue Zone include sweet potatoes, soy foods, turmeric, bitter melon, seaweed, and green teas. Okinawa was once a longevity leader, though modern dietary westernization has eroded this advantage. However, traditional components like purple sweet potatoes and turmeric remain rich polyphenol sources.

Polyphenol-rich foods in Sardinian diets include red wine, coffee, and fruits and vegetables. While Sardinians consume many plant foods, the primary sources of polyphenols in their diet are red wine and coffee. These foods have potential benefits for inflammation, metabolism, and vascular function. Plant foods may also reduce the impact of saturated fats in the diet. These dietary sources, combined with active lifestyles, may underpin Sardinian longevity.

The Mediterranean diet in Ikaria, Greece, includes daily consumption of extra virgin olive oil, which is rich in polyphenols, especially oleuropein, with concentrations ranging from 380 to 939 mg/kg. People in this area also consume wild greens and raw vegetables, including dandelion, onions, and arugula. They drink Greek coffee in moderate amounts and herbal tea made from ironwort.

In Loma Linda, California, primary sources of polyphenols include coffee, citrus fruits and berries, legumes (particularly chickpeas), and nuts and vegetables. Residents of Nicoya, Costa Rica, consume mangoes, papayas, and beans in large quantities.

Polyphenols and Signs of Aging

Polyphenols in Blue Zone diets could prevent deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage and slow telomere shortening. This can be attributed to anthocyanins, which are found in beans and sweet potatoes, and procyanidins, which are found in some grapes and wines. Anthocyanins protect DNA and regulate key pathways that regulate cell survival, while procyanidins promote DNA repair.

Other polyphenols are linked to epigenetic modifications, such as genistein, found in soy, which promotes the activation of tumor-suppressing genes. Chlorogenic acid, which is found in coffee, also prevents harmful gene hypermethylation associated with cancer. Oleuropein, found in olive oil, reduces Alzheimer’s disease-related amyloid deposits in the brain, while curcumin, the bioactive compound in turmeric, reduces oxidative stress. Xanthonoids in mangoes may also delay cell aging.

Polyphenols like genistein reduce inflammation, while oleuropein delays aging via proteasome activation. Some, like quercetin (found in beans), boost energy metabolism, while curcumin also clears damaged mitochondria. Oleuropein and curcumin also enhance autophagy and suppress harmful signals of aging. These effects correspond to polyphenols’ ability to influence aging through a framework known as the "hallmarks of aging," including genomic instability, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation.

Conclusions

Long-lived individuals residing in the world’s Blue Zones are models of healthy aging, their longevity resulting from a combination of environmental and genetic factors. These populations prioritize plant-based foods rich in polyphenols, but more research is needed to understand their impacts.

The authors caution that current evidence linking polyphenol intake to increased human longevity is observational and lacks controlled interventional data. At present, limited epidemiological studies link polyphenol-rich diets to longevity; better tools are needed to measure polyphenol consumption levels that can meaningfully integrate dietary variations across cultures. Without supplementation trials, it is also difficult to isolate the effects of polyphenols.

They recommend future work focus on developing reliable biomarkers to track polyphenol consumption, techniques to measure polyphenol-linked metabolites in human biofluids, and randomized controlled trials to assess how these compounds influence healthy aging.