Very preterm infants are often sick and require antibiotic treatment to save their lives. However, when this form of therapy lasts for 20 months or more, it may affect the gut microbiome over the long-term in addition to its acute effects. Babies who received this type of treatment have less diverse gut microbiomes, and an increased number of drug-resistant microbial genes. They are therefore at increased risk of antibiotic-resistant infections.

A new study was carried out on a group of 32 extremely preterm infants who had to remain on antibiotic therapy for 21 months, another group of 9 infants who were on antibiotics for a week or less but were also extremely preterm, and a control group of 17 infants born at term or late preterm, who had received no antibiotics (or “antibiotic-naïve”). The scientists used a combination of DNA sequencing, cultures and computer-based algorithms to understand the gut microbiome and the kind of resistance genes expressed in these preterm babies who had been exposed to antibiotics both during and after their hospital stay. This was compared to the gut microbiome of healthy babies who had never been given antibiotics.

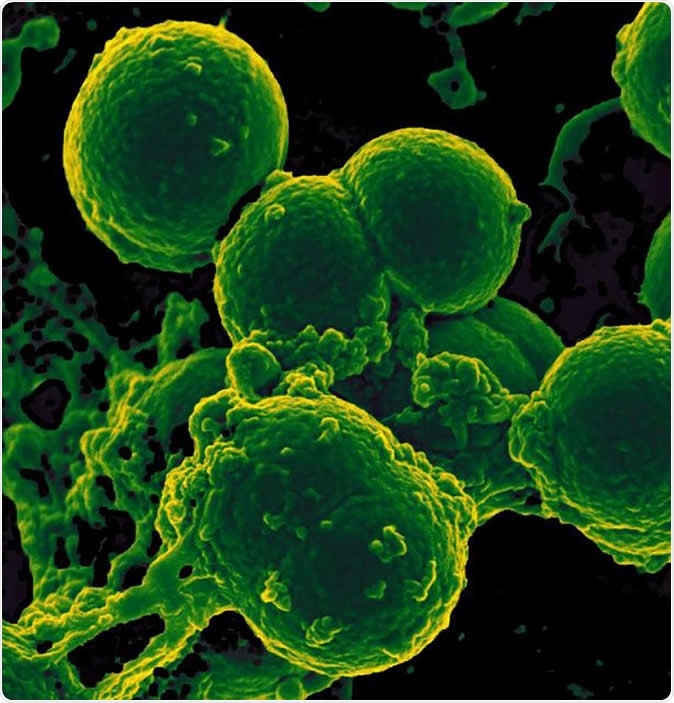

Scanning electron micrograph of neutrophil ingesting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria.Image Credit: NIAID

What did the study show?

The results showed that the number of bacterial species in the infants who had received prolonged antibiotic therapy was significantly reduced compared to the antibiotic-naïve group. Secondly, the number of genes in the gut bacteria that expressed antibiotic resistance were much higher in this group. Moreover, some of these genes for resistance were directed against drugs that the baby had never been exposed to – since these are not usually used in newborns, like Ciprofloxacin or Chloramphenicol. The researchers suggest that these genes may have come from multidrug-resistant bacteria. In this case, being exposed to one of the drugs to which the bacterium is resistant can cause other species to be wiped out, while leaving the resistant strain to proliferate. Moreover, the child will also show resistance to other drugs due to the multiple resistance conferred by the gene – whether or not these drugs were used in that patient or not.

Again, earlier studies show an association between skin allergies, diabetes inflammatory bowel disease, obesity and psoriasis, and antibiotic use in early life. The effects may be trivial but could also promote pathogenic species to grow in the gut, while simultaneously inhibiting the growth of “good” bacteria.

The researchers call these changes in the genome “microbiota scars”. Earlier studies showed an association between allergic skin disorders like psoriasis or skin allergies, diabetes, obesity and inflammatory bowel disease, and treatment with antibiotic during the first year of life.

What do we learn?

Overall, babies who had received antibiotics for a prolonged period of time failed to develop a rich and varied gut microbiome like antibiotic-naïve babies. Antibiotic-exposed babies also shed Enterobacteriaeae, an opportunistic pathogen that was, in this case, drug-resistant. Thus, the species that established themselves in these babies’ guts were driven by their antibiotic resistance. The gut microbiome may be imbalanced in favor of pathogenic species, and resistant infections may occur with greater ease in these children due to their larger resistome (total collection of antibiotic-resistant genes).

In the words of the researchers, “The collateral damage of early-life antibiotic treatment and hospitalization in preterm infants is long lasting. We urge the development of strategies to reduce these consequences in highly vulnerable neonatal populations.”

The article was published in the journal Nature Microbiology on September 9, 2019.

Source:

Journal reference:

Persistent metagenomic signatures of early-life hospitalization and antibiotic treatment in the infant gut microbiota and resistome Andrew J. Gasparrini, Bin Wang, Xiaoqing Sun, Elizabeth A. Kennedy, Ariel Hernandez-Leyva, I. Malick Ndao, Phillip I. Tarr, Barbara B. Warner & Gautam Dantas Nature Microbiology (2019), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41564-019-0550-2?utm_source=feedburner