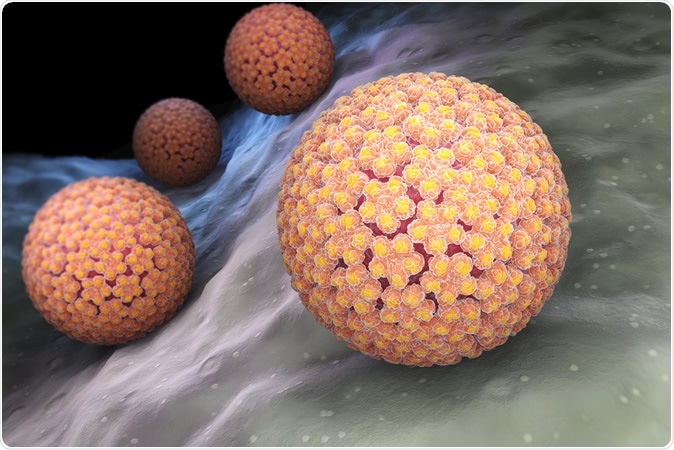

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus from the papillomavirus family. 3D illustration Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva / Shutterstock

Study leader Jiafen Hu, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Penn State College of Medicine called for more research to confirm that papilloma viruses are capable of transmission via blood especially blood transfusions. He said that the blood prepared for receive blood transfusions may require a screening for HPV if this is proven to be true. Hu said, “People who are receiving blood transfusions typically have immune systems that aren't working optimally, so their systems are more vulnerable. We might want to think about adding HPV to the list of viruses for which blood donations are screened, as well as researching whether the typical viral load of HPV in human blood would be sufficient to cause infection.”

Hu explained that the team came across a case in 2005 where a similar transmission was seen. He said, “Some years ago, researchers were looking at blood samples from a group of HIV-positive children, and as they were testing those samples, they found that some of them were also positive for HPV. Because these children were so young, it prompted the question of whether the virus could have come from blood transfusions, which some of the children had undergone.”

Since it is difficult to check for HPV on animal models, the team decided to perform their experiments on other forms of papilloma viruses. “HPV is strictly species-specific,” they wrote, “and thus, cannot be studied directly in animals. Our laboratory has two preclinical animal models with their own naturally occurring papillomaviruses.”

The team used Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus which is commonly used for researching HPV infections in humans because of its similarity with HPV. For their experiments the team first injected the rabbit papilloma virus into the bloodstreams of the lab rabbits. The rabbits were then monitored for four weeks when they were found to develop tumours. This proved that the virus had travelled via the blood stream to cause the tumours in the rabbits said Hu. The team found that several genetic expressions were lower in these rabbit tumours similar to actual sexually transmitted tumours. They wrote, “The rabbit skin tumours induced via blood infection displayed decreased expression of SLN, TAC1, MYH8, PGAM2, and APOBEC2 and increased expression of SDRC7, KRT16, S100A9, IL36G, and FABP9, as seen in tumours induced by local infections.”

Hu explained that in this experiment they had used a large amount of the virus to be injected into the rabbits. This infection due to the injection of the viruses could be due to the heavy viral load, he added. In a normal case of blood borne infection, the dose of the virus could be significantly lower. Thereafter the team reduced the viral load injected by five times. This time the tumours were still seen in 18 out of the 32 animals. Hu said, “We were able to show that the virus in the blood caused tumors, but what about blood transfusions? People receiving a transfusion may only get a very small amount of the virus. To simulate this, we injected the virus into one animal, took 10 millilitres of blood and transfused it into a second animal. We still saw tumors.”

The next question the researchers addressed was if the blood borne infection could cause tumours and cancerous changes in the cervix as the sexually transmitted infection was capable of. Now they repeated their experiment using mice model. When injected with the papilloma virus into lab mice, the team found that the virus and viral warts and tumours were found in the tongue and genital mucosa of the mice. They also found the virus in the stomach mucosa of the mice. This proved that the virus was capable of travelling from the blood stream into oral and genital mucosa as well as into the gastric mucosal surfaces.

Hu added that not all persons who get HPV infection develop cancers but some individuals do. In these individuals, possibility of blood mediated transmission is an important finding. Hu said, “We know that HPV is common and that not everyone who gets it is going to get cancer. The tricky part is that a lot of people who are carrying HPV and are asymptomatic still have the potential to spread the virus. If a person is getting a blood transfusion because of one health issue, you don't want to accidentally add another on top of that.”

The authors wrote in conclusion, “The link between a blood transfusion and an infection or cancer that manifests much later in life would not be easy to detect in hindsight. In view of the results presented here, it would seem prudent to conduct studies on human blood samples to ascertain the need for routine screening to assure safety of the blood supply.”

Journal reference:

Nancy M. Cladel, Pengfei Jiang, Jingwei J. Li, Xuwen Peng, Timothy K. Cooper, Vladimir Majerciak, Karla K. Balogh, Thomas J. Meyer, Sarah A. Brendle, Lynn R. Budgeon, Debra A. Shearer, Regina Munden, Maggie Cam, Raghavan Vallur, Neil D. Christensen, Zhi-Ming Zheng & Jiafen Hu (2019) Papillomavirus can be transmitted through the blood and produce infections in blood recipients: Evidence from two animal models, Emerging Microbes & Infections, 8:1, 1108-1121, DOI: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1637072, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/22221751.2019.1637072?scroll=top&needAccess=true