Scientists have now discovered a pelvis supposed to be that of a pre-human ancestor, called Rudapithecus. Found near a historic mining community called Rudabanya in Hungary, the pelvis is remarkable not only for its rarity – the pelvis being among the fossils most rarely recovered – but also for its structure which shows that the earliest human ancestors stood upright.

This theory, if established, would run directly counter to the currently accepted proposition that our ancestors, at some point took to the practice of standing upright rather than going on all fours. The basic difference between modern African apes and humans is that the apes are much larger, so that they have a long pelvis and short lumbar spine, which promotes their all-fours gait on the ground.

Rudapithecus hungaricus, which resembles modern African apes as well as humans, is said to have climbed in an ape-like manner among the branches, using chiefly its arms while holding its body straight. However, its pelvis shows a wider upper portion in the thigh bone socket, which is typical of the upright position. It also has a shallow socket, and a short ischium, which allows ape-like mobility of the hip.

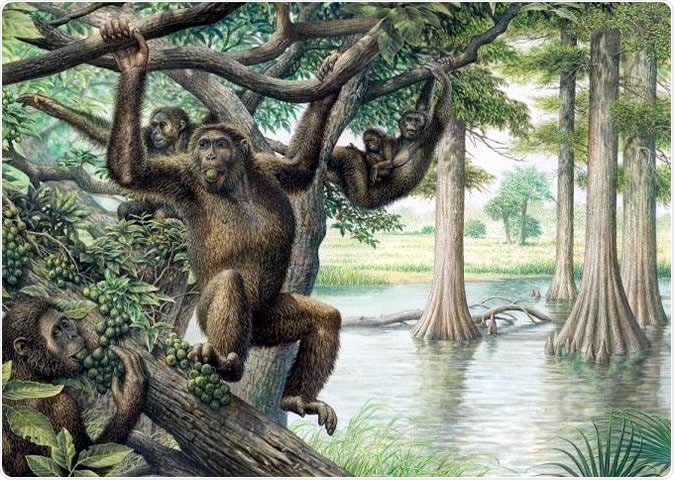

Rudapithecus was pretty ape-like and probably moved among branches like apes do now -- holding its body upright and climbing with its arms. However, it would have differed from modern great apes by having a more flexible lower back, which would mean when Rudapithecus came down to the ground, it might have had the ability to stand upright more like humans do. Illustration courtesy of John Siddick

Similar to modern apes, its iliac blades are oriented sideways, with a flared shape, which indicate that the area where the spinal muscles attach to the spine is reduced. This in turn shows that the spine was stiff to some degree. On the other hand, the lower part of the ilium is short, quite unlike that seen in the modern great apes like chimpanzees and orangutans. This modification is associated with a lesser number of lumbar vertebrae, only 3-4 in modern apes as compared to 6 in humans. The individual lumbar vertebrae are also shorter. This results in a shorter lumbar spine and in turn decreased flexibility of the lower back. This is indispensable to allow tree climbing, hanging from aerial supports, and bridging behavior, as it imparts passive stability to the spine – the ability to keep the backbone stiff without too much muscular effort – while providing a stable support from which the latissimus dorsi, the primary muscle that enables the animal to bring the arm in towards the body, can act. . This is even more exaggerated in the larger modern great apes.

These characteristics show that it was a much smaller animal, only about the size of an average dog. This would mean it had a longer lumbar spine, giving its lower back greater flexibility – a characteristic of human gait. Thus it could stand upright when on the ground. Such an animal could have more easily given way to the typical human skeletal structure than the long and detailed list of changes that would have been necessary for apes, including shortening of the pelvis and the lengthening of the lumbar spine. Hence the supposition that human ancestors never did walk on all fours, in the first place.

The researchers came to the conclusion that the presence of a long lower ilium in modern apes was not necessary for them to adopt the upright posture or for swinging among branches using mainly the forelimbs. Instead, the ilial length could be an independent feature appearing in each great ape family by itself. Thus the hypothetical last common ancestor of apes and men could well have had a different ilial shape making it easier to imagine its transition to a fully human morphology. This hipbone is thus thought to be the earliest fossil from a hominid that shows changes towards the upright position.

The incompleteness of the Rudapithecus fossil made it necessary for the researchers to use new 3D modeling tools to formulate its hypothetical shape. This was then compared with that of modern animals. They hope to examine other Rudapithecus fossils using 3D analysis to get better insights into how this animal moved.

The study was published online in the Journal of Human Evolution on September 17, 2019.

Journal reference:

A late Miocene hominid partial pelvis from Hungary. Carol V.Warda, Ashley S.Hammond, J. Michael Plav, and David R.Begun. Journal of Human Evolution. 17 September 2019, 102645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102645. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248419300685?via%3Dihub