A new study published in the American Heart Journal used spectroscopic imaging techniques to ‘see’ fatty plaques in the arteries of ancient mummies. This shows that the people of ancient times also had a high incidence of clogged arteries, showing that heart disease is of very old lineage.

Ancient mummy in the sarcophagus, close-up. Image Credit: Anton Watman / Shutterstock

Older studies used dissection to find arterial lesions. In more recent times, scientists switched to the use of computed tomography (CT) scans to look at mummified hearts and arteries. This technique, which relies on a computerized assimilation of numerous X-rays taken from a variety of positions, allowed a detailed visualization of the blood vessels, bones and organs. However, it detects only calcium deposits within the arterial walls and not the fatty plaques themselves.

The current study uses another technique called near-infrared spectroscopy – the first time this has been applied to mummified arteries. This was used to reveal the state of arteries in mummified bodies from all over the world, both in South America, Europe and Asia. Researcher Mohammed Madjid explains how it works: “A catheter is placed on the sample and it sends out signals. The signals bounce off the tissue and come back. You can tell the difference between various tissue components because each has a unique molecular signature like a fingerprint.”

UTHealth's Mohammad Madjid, MD, MS, says people in ancient times had clogged arteries too. Image Credit: Maricruz Kwon/UTHealth

The presence of atherosclerotic plaque is diagnosed from the signature’s correspondence with the already known reflected signal from a fatty plaque specimen. This technique has been used in many studies to find cholesterol-rich plaques, both in animals and in humans. It has also been used to examine the chemical composition of a range of samples.

The current research is only intended to serve as a proof-of-concept, showing that this technique works for this application. It focused on five mummies from different continents, three men and two women of various ages from 18 years to about 60 years. The cause of death is thought to have been pneumonia in three cases, and kidney failure in one, while in the last case it is unknown. Four of them were found in South America, one from the Middle East. They are thought to be from the period 2000 BC to 1000 AD.

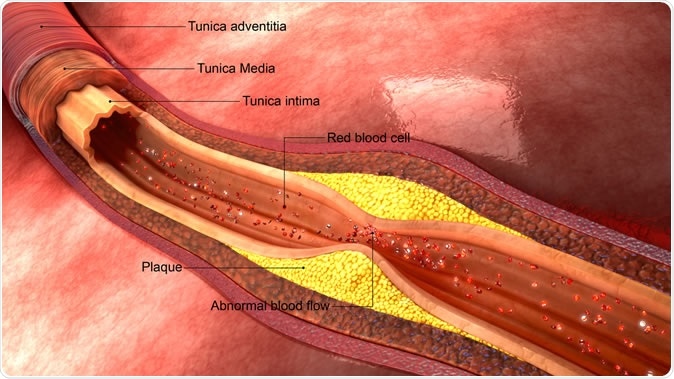

The study looked for any evidence that these people had suffered arterial damage due to atherosclerosis. This is a term that refers to the accumulation of cholesterol within plaques, or bulging deposits, within the arterial wall. The enlarging plaque reduces the flow of blood to different parts of the body, and therefore deprives tissues of oxygen. When the heart muscle doesn’t get oxygen because of obstruction to the coronary arteries that supply it with blood, a heart attack is the result.

Atherosclerosis 3d illustration Image Credit: Sciencepics / Shutterstock

The researchers found cholesterol-rich plaques in all the mummies. Most of these plaques lacked calcified foci. This confirms that the fibroatheromatous plaque is the characteristic sign of early atherosclerosis. Calcification is a late sign, not present in many of these plaques. The presence of calcification will therefore not indicate the true frequency of the disease. The usefulness of near-infrared imaging as compared to CT imaging in the study of early atherosclerosis is therefore confirmed by this study.

One of the chief hallmarks of atherosclerosis is the accumulation of cholesterol within the plaque. These lesions, called fibroatheromas, are capped by a thin membrane of vascular lining cells, or endothelium. These are to blame in about two-thirds of heart attacks and other acute coronary syndromes.

By showing the widespread occurrence of cholesterol plaques in a range of older civilizations in different locations, the study throws light on how the condition develops in its early stages. The samples comprised people from cultures who were much more physically active than the average modern man, and presumably ate a much healthier diet, including abundant fish in the case of the South American people. The reasons for heart disease could range from smoke exposure due to open-fire cooking, to bacterial infections as well as genetic factors. This would lead to chronic inflammation at a low level, which stimulates the response-to-injury that results in atherosclerosis. This might also be why these relatively young samples showed evidence of fatty plaques at a young age, compared to the expected age.

Now that the utility of this technique has been proved, the researchers plan to continue their work on additional mummies. As the report says, “Noninvasive near-infrared spectroscopy is a promising technique for studying ancient mummies of various cultures to gain insight into the origins of atherosclerosis.”

Journal reference:

High prevalence of cholesterol-rich atherosclerotic lesions in ancient mummies: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Mohammad Madjid, Payam Safavi-Naeini, and Robert Lodder. American Heart Journal 2019;113–116.0002-8703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2019.06.018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002870319301711