In a world-first, scientists have established the cause of antibiotic-resistance in bacteria, capturing video footage showing that bacteria have the ability to change their form in order to avoid detection by antibiotics.

This contradicts existing beliefs around how bacteria can survive without a cell wall. Known as L-form switching, this ability to evade antibiotics poses a significant threat to global health.

fusebulb | Shutterstock

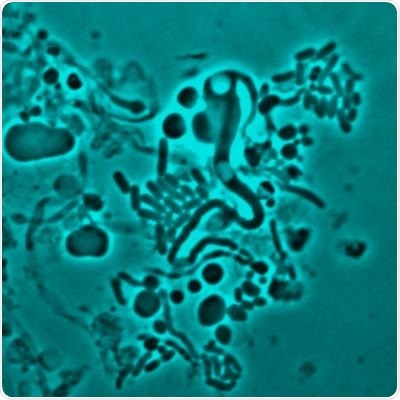

fusebulb | Shutterstock

Published in Nature Communications, the research team from the Errington Lab at Newcastle University studied urine samples from elderly patients who were experiencing recurring urinary tract infections. They were able to see that bacteria could lose their cell wall, which is a commonly used target for a wide range of different antibiotics.

Lead author of the study and researcher at Newcastle University Dr Katarzyna Mickiewicz explained how antibiotics usually detect bacteria using their cell wall.

Imagine that the wall is like the bacteria wearing a high-vis jacket. This gives them a regular shape (for example a rod or a sphere), making them strong and protecting them but also making them highly visible – particularly to human immune system and antibiotics like penicillin.”

Mickiewicz continued: “What we have seen is that in the presence of antibiotics, the bacteria are able to change from a highly regular, walled form to a completely random, cell wall-deficient L-form state – in effect, shedding the yellow jacket and hiding it inside themselves.

“In this form, the body can’t easily recognize the bacteria so doesn’t attack them – and neither do antibiotics.”

Discovering an ‘underappreciated mechanism of antibiotic tolerance’

The study was carried out in collaboration with clinicians at the Newcastle Freeman Hospital part of Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation Trust, organized by Dr. Phillip Aldridge and Dr. Judith Hall, who provided the urine samples needed to study the bacteria.

The study was carried out in collaboration with clinicians at the Newcastle Freeman Hospital part of Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation Trust, organized by Dr. Phillip Aldridge and Dr. Judith Hall, who provided the urine samples needed to study the bacteria.

Researchers studied samples from 30 patients aged 65 and over with a history of recurring urinary tract infections. The results showed that L-forms of a variety of bacterial species linked with urinary tract infections (E. coli, Enterococcus, Enterobacter and Staphylococcus) were present in 29 of the 30 patient samples.

Through direct microscopy, the team was able to show L-form switching in vivo, in this case in a transparent zebrafish model, and not only in artificial laboratory conditions.

This is in addition to the first of its kind video footage of L-form bacteria re-forming its cell wall after antibiotics had been removed, a process that took just five hours.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that antibiotic resistance is “one of the biggest public health challenges of our time”, citing a previous analysis of antibiotic-resistant threats in the US that claimed “at least 2 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and at least 23,000 people die” every year.

A particularly concerning discovery made by the research team’s investigations is that L-form bacteria are able to proliferate during long periods of antibiotic treatment, which can last from five to 14 days, meaning the infection can continue to grow while antibiotics are working in the body.

They were also able to show that L-form bacteria can revert back to their walled state after antibiotics are removed.

The authors describe this as a possibly “underappreciated mechanism of antibiotic tolerance by bacteria in other recurrent or chronic infections.”

transition on osmoprotective mediafrom L form to walled form after the antibiotic was removed

Applying the findings to the clinic

“In a healthy patient, this would probably mean that the L-form bacteria left would be destroyed by their hosts’ immune system. But in a weakened or elderly patient, like in our samples, the L-form bacteria can survive, said Dr. Mickiewicz.

“They can then re-form their cell wall and the patient is yet again faced with another infection. And this may well be one of the main reasons why we see people with recurring UTIs.

“For doctors, this may mean considering a combination treatment – so an antibiotic that attacks the cell wall then a different type for any hidden L-form bacteria, so one that targets the RNA or DNA inside or even the surrounding membrane," he added.

Along with struggles to treat infections with L-form bacteria, the study identified struggles doctors may have difficulty in identifying the L-form bacteria using conventional methods used in hospitals, which includes using a gel that “pops” bacteria when they come into contact with it.

Instead, an osmoprotective detection method was required to identify the L-form bacteria, which are weaker than walled bacteria but still very able to survive and spread.

The authors conclude the study by suggesting that a “combination of cell-wall-targeting antibiotics with other classes of antibiotics, such as those targeting the bacterial membrane” may be an effective way of beating recurrent infections where L-form bacteria are present.

Journal reference:

Mickiewicz, K., et al. (2019). Possible role of L-form switching in recurrent urinary tract infection. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-12359-3.