The well-known cancer gene, p53, which researchers had thought was less relevant in kidney cancer, may play an important role after all – a discovery that could potentially lead to new treatments.

A study conducted by researchers at Thomas Jefferson University suggests that the second-most mutated gene in kidney cancer – PBRM1 - is strongly linked to the inactivation of the p53 pathway. Since PBRM1 is also found in many other cell types and cancers, the finding may have implications for other types of cancer.

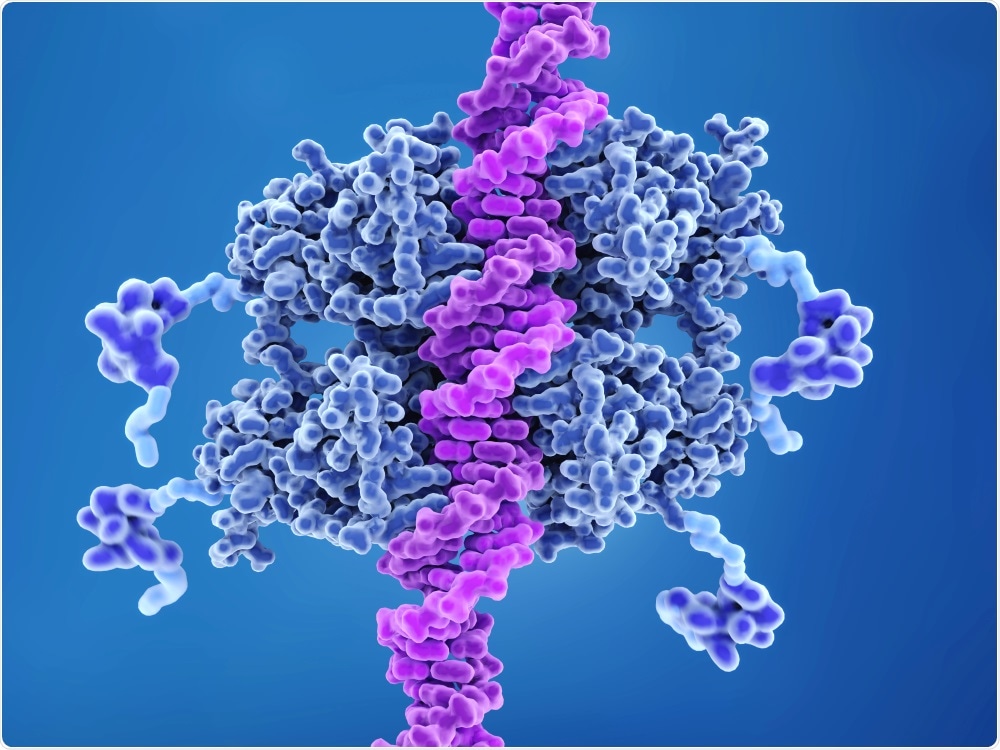

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock.com

What is the p53 gene?

The p53 gene is the most well-known cancer gene. It is involved in more than half of all cancers and inactivation of its pathway in cancer is well understood. The gene encodes for the tumor suppressor protein p53, which regulates cell division by preventing cells from proliferating too quickly or in an uncontrolled manner.

When DNA in cells becomes mutated, p53 plays a key role in determining whether it gets repaired or whether the cell will undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis). If the DNA cannot be repaired, p53 stops the cell dividing and signals it to self-destruct.

By preventing the division of cells with mutated DNA, p53 helps to stop tumors developing. If a cell loses the p53 gene when DNA becomes mutated, the cell proliferates in an uncontrolled way and does not self-destruct.

However, certain cancers, such as kidney cancer, have few p53 mutations.

Haifang Yang, a researcher at the university’s Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center wanted to know whether inactivation of the p53 pathway may somehow still be involved in kidney cancer.

Probing for p53 in kidney cancer

As reported in the journal Nature Communications, Yang and colleagues probed genes that are known to be involved with kidney cancer for interactions with p53.

The second most mutated gene in kidney cancer is the tumor suppressor PBRM1 and research has previously suggested that this gene may interact with p53. However, so far, researchers have been unable to confirm whether this is an important mechanism in kidney cancer.

Rather than studying the p53 protein itself, Yang and team looked at an activated version of p53 that has an additional chemical marker - an acetyl group - at certain spots.

The researchers examined whether PBRM1 can "read” or translate this activated version. Using a range of biochemical and molecular techniques to test both human cancer cell lines and tumor samples from humans and mice, they found that PBRM1 binds to p53 using its bromodomain 4. However, PBRM1 only does this when p53 is in its activated form, with the acetyl group at one specific spot.

Mutations cause PBMR1 to lose its tumor suppressor ability

If this bromodain 4 has tumor-derived point mutations, this interaction can be disrupted, and PBMR1 loses its ability to suppress tumor growth.

Yang says the finding suggests that even though p53 is not directly mutated in many kidney cancers, the cancer still disrupts the p53 pathway and drives cancer initiation and growth.

“This suggests that there might be a therapeutic window for drugs that activate the p53 pathway, which may preferentially impact PBRM1-defective kidney tumors while sparing normal tissues," he adds.

Since PBRM1 is also found in other cell types and cancers, the finding could be applicable to other types of cancer.

What’s next?

Next, the researchers plan to determine whether there is indeed a therapeutic window and whether it can be combined with known therapeutics. They also plan to explore which kidney tumor genotypes are most likely to respond to treatments.

Journal reference:

Cai, W., et al. (2019). PBRM1 acts as a p53 lysine-acetylation reader to suppress renal tumor growth. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13608-1