All life forms need sunlight to survive and not getting enough may impact health and well-being. There is a growing body of evidence that getting enough sunlight can promote optimum health. A new study supports this claim as scientists found that fat cells deep in the skin can detect sunlight and not getting enough can increase the risk of metabolic disruption.

The modern lifestyle of people today limits the body’s natural light exposure, which is from the sun. More people are staying indoors, exposed to unnatural lighting spectra, with people working shift jobs, being exposed to light at night, and staying indoors throughout the day.

A team of researchers at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center wanted to determine how the human body responds to sunlight and the effects of not getting adequate exposure on body processes. Published in the journal Cell Reports, the study reveals that the implications of sun exposure are more than just staying warm.

The team studied laboratory mice and how they control their body temperature. They found that light exposure helps regulate how two types of fat cells work hand in hand to create the raw materials needed for other cells in the body uses for energy. Once this fundamental metabolic process is disrupted, it can lead to an increased risk of developing an illness.

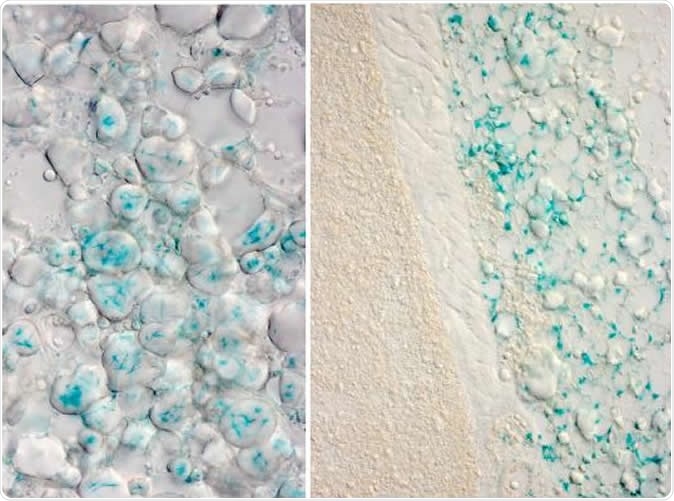

These images show expression of the OPN3 gene (in blue) in white fat cells of mice in two locations. The right panel shows interscapular white adipocytes (above a layer of muscle and above brown adipose tissue). The left panel shows white adipocytes from the inguinal adipose depot. Image Credit: Cincinnati Children's

Disruptions in how the fat cells produce energy may reflect an unhealthy face of modern life, which is spending too much time indoors and not getting enough sunlight exposure.

“Our bodies evolved over the years under the sun's light, including developing light-sensing genes called opsins. But now we live so much of our days under artificial light, which does not provide the full spectrum of light we all get from the sun,” Dr. Richard Lang, a developmental biologist and senior author of the study, said.

The body’s response to sunlight

Almost all life forms can detect and decode light information for adaptive advantage. For instance, the visual system of the body contains photoreceptors that can detect light. These signals from the sun or light are processed into virtual images. Further, the body’s internal clock or the circadian rhythm relies on the light of the sun to determine if it’s time to sleep or wake up.

Though there are many bad effects of sunlight exposure to the body, such as being exposed to the harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun, or gamma radiation, it can’t be denied that sunlight has many health roles in the human body.

For one, sunlight exposure is needed in the synthesis of vitamin D, which plays a major role in maintaining healthy bones and teeth and protecting the body against a wide range of diseases.

The new role of sunlight

In the study, the researchers noted that despite the mouse having fur, or a person having clothes, light can still penetrate the skin and into the body. Once the light enters the skin, photons, which are vital particles of light, may slow down and scatter around once they pass the outer layers of the skin. When these light particles enter the body, they can impact how cells behave.

The team analyzed how laboratory mice respond to exposure to frigid temperatures of about 40° F. Just as humans when mice are exposed to cold temperatures, they shiver. Shivering or shuddering is a body function in response to cold in humans and other warm-blooded animals, which is due to the skeletal muscles shaking in small and frequent movements to produce heat.

Studying further, the scientists found that the internal heating process in response to cold exposure is compromised when a gene called OPN3, an opsin, is absent and being exposed to a 480-nanometer wavelength of blue light, which is a natural part of sunlight but occurs in low levels in most artificial lighting.

When the OPN3 is exposed to light, it triggers white fat cells to release fatty acids into the blood. These fatty acids are helpful for cells as a form of energy to fuel cellular activities. On the other hand, brown fat burns the fatty acids to produce heat to warm up the body when in cold temperatures, in a process known as oxidation.

Mice without the OPN3 gene, they can’t produce heat or warmth as much as other mice when exposed to cold temperatures. Astonishingly, even the mice with the right gene can’t warm up when they were exposed to light without the blue wavelength.

Further research is needed

The researchers conclude that sunlight is essential and necessary for normal energy metabolism in mice models. However, they suspect that if that is the case in mice, it might be true for humans, too. Further research is needed in humans to strengthen their findings.

“Based on the current findings, it is possible that insufficient stimulation of the light-OPN3 adipocyte pathway is part of an explanation for the prevalence of metabolic deregulation in industrialized nations where unnatural lighting has become the norm,” the researchers concluded in the study.

“Our modern lifestyle subjects us to unnatural lighting spectra, exposure to light at night, shift work, and jet lag, all of which result in metabolic disruption. Based on the current findings, it is possible that insufficient stimulation of the light-OPN3 adipocyte pathway is part of an explanation for the prevalence of metabolic deregulation in industrialized nations where unnatural lighting has become the norm,” they added.

More studies are needed to determine the health effects and therapeutic value of light therapy. It may take a couple of years before the theory can be tested on humans.

Journal reference:

Adaptive Thermogenesis in Mice Is Enhanced by Opsin 3-Dependent Adipocyte Light Sensing Nayak, Gowri et al. Cell Reports, Volume 30, Issue 3, 672 - 686.e8, https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)31700-0