It started when an increasing number of anecdotal reports began coming into my email inbox, or to our charity Fifth Sense, which I am a trustee of.

Fifth Sense looks after patients suffering from smell and taste disorders. As a clinician, I run a specialist service for these patients, and so as it started to emerge as another possible symptom, and potentially a harbinger symptom in people who may otherwise be asymptomatic with COVID-19, it was an important thing to research.

What are the common symptoms of coronavirus?

The two keys symptoms that are publicized by Public Health England and the World Health Organization, are fever and dry cough.

Image Credit: Yaoinlove/Shutterstock.com

This then progresses to respiratory difficulty, shortness of breath, and then there are a number of other symptoms that have been suggested in the background such as GI disturbances, diarrhea, other upper respiratory symptoms, muscle aches, general fatigue- the typical viral symptoms.

Smell loss has not been officially recognized as a symptom to look out for, even though it is now starting to get mentioned in TV and media coverage occasionally. My colleague, who is the president of ENT UK, appeared on Newsnight a couple of nights ago and mentioned this as well.

Therefore, it is getting some notice, but it has not become an official World Health Organization or Public Health symptom to look for yet.

There is an app in which people can track their symptoms of COVID-19. Why is it important for individuals to track their symptoms?

The app is used to turn what is anecdotal evidence into definitive evidence.

There are key problems, however. Data was released recently from King’s College in London from the COVID-19 app tracker in which only 0.1% of the people responding have actually been tested for COVID-19. This means that there are two problems.

The first problem is the number of tested people you can confirm these symptoms in, and how this compares to the general loss of smell that you might temporarily get with a cold, along with other viruses that circulate at this time of year already.

The other big problem is knowing the denominator, that is how many people are affected overall. Then, how many people, therefore, is the smell loss a percentage of. So far, I have seen percentages ranging from 10% of cohorts from China that are reporting smell loss, all the way up to a study that reported 80% in a group of patients.

I believe what makes the strong case behind this symptom being COVID-19 related is the reports that have described there being affected healthcare workers in other countries. Italy, for example, have had reports of medical teams reporting smell loss after contact with an infected patient.

Therefore, the more we test healthcare workers that have reported smell loss, the better certainty we can have as to whether this is a symptom and what percentage of people are affected by it.

What is the relationship between smell and taste?

The relationship between smell and taste is more in our language rather than in true physicality.

In the English language and this is also common in Western culture, we talk about tasting food, when actually what we mean is that we appreciate the flavor of food.

When we eat food, we smell and taste at the same time, so people find it difficult to separate those two events. From a medical perspective, taste is what you do with your taste buds, which are found on the tongue, but also in other parts of the mouth and the top of the throat. Those taste buds pick up the sensation of salt, sweet, sour, bitter, and savory sensations known as umami.

Everything else is about flavor. For example, if you eat a pork sausage with herbs in it, most of what people refer to, colloquially, as taste, is actually flavor. The only thing you would really get from that sausage, if you could not smell, would be a savory sensation from the meat, and perhaps if there were some salt in it, you might get a salty sensation.

When you put food inside your mouth, you breathe the aroma of food back out through your nose. It is a kind of reverse inhalation, so you exhale by your nose and the aroma of the food travels up past the smell receptors.

At the same time, the food is tasting on your tongue- the two things happen together. Another example is when people talk about sweet smells such as vanilla. This is because inevitably, whenever you smell vanilla, you will probably be tasting it in a sweet dessert, so there is sweetness within the sugar involved also.

Image Credit: MicroOne/Shutterstock.com

Therefore, language-wise, you associate the two things together, even though they are separate events.

In my specialist clinic, for every 100 patients that complain of smell and taste problems, only about one of those will actually have a taste disorder. The majority will have just a smell problem.

Is anosmia a common symptom of viral infections? Why is this?

Smell loss, or anosmia, can happen to varying degrees during common respiratory tract infections from viruses (the common colds).

Usually, this is because people's noses are congested and, therefore, their airflow into the top of their nose is reduced.

There is a lot of thickened mucus in the nose also, which also impairs airflow to the top of the nose. In a small number of cases, the patients I typically see in my routine clinics, about one in four will have what we call post-viral smell loss.

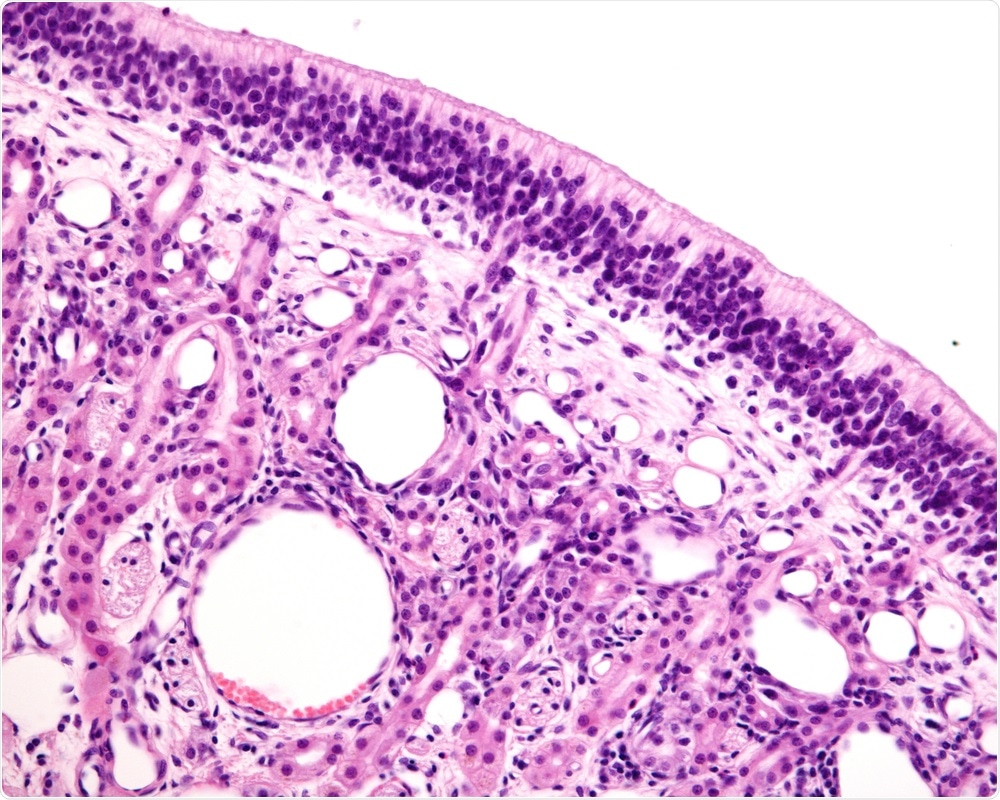

How can viruses damage smell receptors?

In post-viral smell loss (which accounts for around 11 to 12% of all causes of smell loss), they have had a cold and all the usual symptoms, including the sense of smell going- however, whilst all the other symptoms have gone, their sense of smell has not come back.

In these cases, if you carry out microscopic studies of the tissue, you can see that the virus has damaged the structure of the receptor cells.

Typically, you will see that the fine hair endings that dangle down into the mucus have dropped away, therefore the cells cannot pick up any smells from the nasal mucus.

Image Credit: Jose Luis Calvo/Shutterstock.com

How could COVID-19 be causing anosmia?

Early data from initial research on COVID-19 is suggesting the mechanism of injury in this coronavirus. A theory is that the virus is injuring the supporting cells that interconnect with the receptor cells rather than the receptor cells directly.

This would cause a lot of swelling in the general tissue level rather than the receptor cells specifically. We think that the reason why a lot of the people who are reporting smell loss with COVID-19 are regaining it fairly quickly is that their receptor cells are not being specifically injured.

There is also some emerging evidence that, in some people, the coronavirus is invading the nerve tissues, causing a central effect in some of the deeper structures in the brain.

This could explain why some people are doing badly even when they are on a ventilator. The area of the brain that controls breathing could be being affected by the virus, rather than their lungs specifically.

Therefore, it is possible that the same may be happening with smell and that there is an impact upon the nerve pathways involved in smelling.

Do you believe that COVID-19 enters our body easier through the nose than through the mouth?

I do not know if it enters easier through the nose or mouth, but the key thing is that the virus enters through the respiratory tract, because that seems to be the main port of infection after people make contact or they touch something and then their face.

Image Credit: Andrii Vodolazhskyi/Shutterstock.com

What is clear is that the nose is the highest area of viral load or viral shedding, so when the virus reproduces and exports copies of itself, the nose is the most dangerous place in the airway with COVID-19.

Should the World Health Organization and Public Health England include this symptom as a warning sign?

I think so. I am part of a global consortium called the GCCR, which was set up a week or two ago to try and establish a global survey of this problem.

All of us around the world are seeing reports coming in through ear, nose, and throat specialists or through doctors in general, that sudden onset smell loss has been on the increase with the rise of COVID-19.

This means that even if someone is otherwise well, they are at risk of transferring this to other people. Therefore, there should be a guideline to say that if your sense of smell has gone suddenly, stay at home. It might not be COVID-19, but it is safer to self-isolate and not risk spreading it to other people until you have had a clear period.

If anosmia is recognized as a warning sign for COVID-19, could this be used to prevent its spread?

Potentially yes, because if there are a number of people out there who only lose their smell and otherwise remain well, they might carry on as normal if they are not aware of this being a possible symptom.

A lot of people are being made to stay at home anyway, but if some people are going into work, particularly in the healthcare profession, and they have lost their sense of smell but otherwise they feel okay, they could be inadvertently spreading it to their colleagues without realizing.

Could there be individuals that suffer from a permanent loss of smell due to COVID-19?

That is the next question, which the coming weeks and months will tell. I wonder if I am going to see a sudden surge in referrals, after the initial peak of activity's died down, from people who have got a more permanent loss of smell.

Image Credit: Big Foot Productions/Shutterstock.com

At this stage, we just don't know, as it is too early to say. Once the peak has come and gone, it is only then that we will really know whether there is an additional group of COVID-19 patients who are anosmic permanently or for a longer time.

What further research needs to be carried out to further determine the relationship between COVID-19 and anosmia?

I think that once we know who the COVID-19 positive patients are, and once we know who the patients with smell loss are, it is about following those patients long-term. There should be a way of tracking people over time to know whether these symptoms have resolved spontaneously or whether there is a group of people that will then have a residual problem.

Coronavirus outbreak aside, we get a lot of contact at our charity Fifth Sense from people who lose their sense of smell and get in touch looking for answers.

I think the work that we are doing through the charity will allow us to get some insights on this because we will see whether there is suddenly an increasing group of people looking for help through our charity.

Does COVID-19 change anything about knowledge of anosmia?

No, I don't think so in terms of our general knowledge of anosmia. I think what it has done is catapult smell loss as a symptom to the forefront, whereas before, it has been very much a neglected symptom.

I have been championing smell loss for over a decade now, and so going forward I hope that research continues into this area and that it gets some better recognition in the future.

How do you feel knowing that the loss of smell and taste is now recognized as an official symptom of COVID-19?

I feel relieved that after weeks of campaigning that smell/taste loss is clearly linked to COVID-19, it has finally been recognized.

But I am left wondering how many people might have transmitted the infection without being warned.

It also does, at last, put smell loss in the spotlight after years of campaigning for its recognition.

Where can readers find more information?

Read about the Fifth Sense charity here

Read more about coronavirus and smell loss here

Read more about smell loss disorders here

See more of Professor Carl Philpotts publications here

About Professor Carl Philpott

Carl was appointed as an academic surgeon to the University of East Anglia in 2010, funded in part by the Anthony Long Trust. As Professor of Rhinology & Olfactology at UEA, he leads on a number of research projects related to chronic sinusitis and smell and taste disorders.

In conjunction with his colleague Claire Hopkins, they lead the MACRO Programme Grant awarded by NIHR for £3.2 million, supported by a team of colleagues from UCL, the University of Southampton and the University of Oxford. The program involves a major trial of 600 patients with chronic sinusitis across 16 centers in the UK.

Other research roles include being ENT Lead for the Eastern Local Clinical Research Network, Research Lead for the British Rhinological Society where he has helped to shape the national research priorities for nose and sinuses diseases and Vice-President of the British Otorhinolaryngology & Allied Sciences Research Society.

Carl is a graduate of Leicester University Medical School and completed his basic surgical training in the University Hospitals of Leicester before undertaking a period of research into developing apparatus for testing the sense of smell, which culminated in an MD Thesis.

His specialist training was completed in East Anglia, during which time he spent a year at the St Paul’s Sinus Centre in Vancouver, Canada learning advanced skills in endoscopic sinus surgery for inflammatory diseases of the nose and sinuses as well as tumors of the sinuses and anterior skull base. Carl's main clinical interests include the medical and surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, and other sino-nasal disorders.

He established the first dedicated ENT image-guided sinus surgery facility in East Anglia and now runs a regular sinus surgery course at UEA.

Carl has also spent time at the Dresden University Smell & Taste Clinic learning techniques for assessing and researching the sense of smell and is now the Director of the first British Smell & Taste Clinic and receive referrals from around the UK.

This provides the opportunity to research the impact of olfactory disorders on sufferers and is now currently running a trial for a potential new treatment for a reduced sense of smell. Furthermore, he helped establish a patient-led charity, Fifth Sense, which now has over 2500 members around the UK.