The COVID-19 pandemic is spreading over the world, causing panic and illness on a scale unprecedented in one hundred years. Even while the death toll nears 100,000, with over 1.5 million confirmed cases worldwide, public health experts and medical professionals are battling it using all the weapons available. Unfortunately, these are all too few.

Now, engineers have come out with the offer to make as many of a relatively new and efficient type of drug/vaccine delivery systems as are needed for research on vaccine development and the treatment of this condition to continue.

The technology – microneedle arrays

Dissolvable microneedle arrays are a very effective, safe, and rapid method of delivering drugs into the human body. The production technique for this technology was developed by Burak Ozdoganlar of Carnegie Mellon University, who has been working on and refining the arrays since 2006.

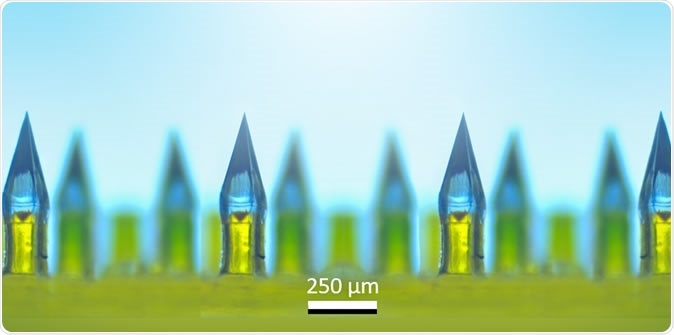

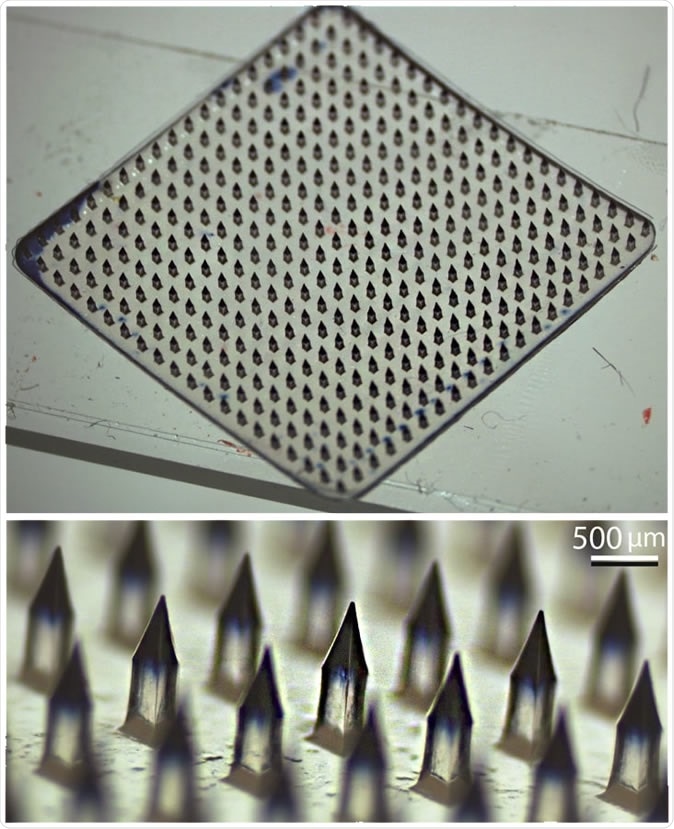

Microneedle arrays contain hundreds of painless, dissolvable, tiny needles clustered on a miniature patch for delivery of vaccines or medications. Image Credit: Ozdoganlar / Carnegie Mellon

Microneedle arrays are an innovative cluster of hundreds of tiny needles, made of a biodegradable sugar-like natural substance. The drug or substance that is to be delivered with the microneedle array is dissolved or mixed into this water-soluble substance before it is solidified into the needles. The whole array is mounted on a patch the size of a fingertip.

The drug or vaccine is applied by putting the patch on the skin. The microneedles cause no pain or pricking, nor bleeding, only a sensation rather like Velcro.

Burak Ozdoganlar: Micro-needle Patches for Advanced Drug Delivery

“We are here to do our part”

The scientist says they would be happy to manufacture the microneedle patches for use by researchers on vaccines and treatments. At present, researchers are testing the utility of arrays in delivering chemotherapy to treat skin cancer, but they could easily be used this way as well.

Vaccine or antibody delivery is a particularly appropriate indication because the tiny abrasions produced by the vaccines induce a rapid and potent immune cell response despite the minute amount of the vaccine material. In contrast, intramuscular vaccines cause a much less powerful response with the same amount of material.

Ozdoganlar has been developing and innovating microneedle array drug delivery devices since 2006. Image Credit: Ozdoganlar / Carnegie Mellon

These patches were recently put to use for testing out the PittCoVacc, and were initially developed by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center as well as Carnegie Mellon University. Now, Ozdoganlar says he is looking for scientists to work with him on developing a therapy or a vaccine for the SARS-CoV-2 that is causing the current pandemic. Describing the nature of the collaboration, he says, “My lab can fabricate hundreds of microneedle arrays with your viable vaccine or antiviral drug very quickly for testing in your vaccine and drug development, and we can ramp up to thousands if needed.”

And the offer goes beyond the experimental stage. The investigator says his group can help with the manufacture of a proven vaccine once it is identified. Throwing the weight of his formidable expertise and experience with the microneedle arrays, as well as promising to use his connections to achieve the best possible output, he says, “We can provide the necessary expertise, experience, and connections to scale up the manufacturing of the vaccine patches using Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines to the levels that will effectively address the COVID-19 vaccination needs.”

Are coronavirus vaccines on the horizon?

Vaccine development against the novel coronavirus is, meanwhile, moving towards the stage of human trials. Both commercial and academic researchers are in the race. A few have already entered phase I trials, meaning they are being tested for safety in a very small number of human volunteers. This kind of speed is because of the early Chinese sequencing results that made the genome of the virus available to the whole world in January. This was invaluable in allowing the culture of the virus in live cells, where the effects of infection could be studied.

A second reason for the early success in identifying candidate vaccines is the work already accomplished on prototype pathogens. Some of these come from vaccine development efforts directed against the MERS and SARS viruses, even though these never saw the light because of the dying down of the outbreaks.

Vaccine development is branching out from the time-tested methods of using live attenuated strains of the disease-causing agent, or a part of the virus which is antigenic, to recombinant vaccines that depend on the production of viral antigens by bacterial or yeast cells into which the genes encoding these antigens are inserted. Another approach is to create vaccines from the genetic code of the virus itself.

Yet vaccine trials are not to be hurried, as they ensure safety and efficacy. Moreover, some organizations are gearing up to put a manufacturing line in place at the same time, so that a vaccine that gains approval can be rolled out as fast as possible. Against this backdrop, the offer of manufacturing facilities for microneedle arrays could be a game-changer in reducing the cost of vaccine trials and promoting fast, efficient production if the vaccine proves successful.