Purdue University researchers have discovered a laser treatment to texture metals that can potentially transform almost any metal surface into one that quickly eliminates any bacteria that come into contact with it. The study, published in the journal Advanced Materials Interfaces in April 2020, could help break transmission chains of common superbugs and cut down the number of infections that result from indirect spread through such surfaces.

Purdue University engineers have created a laser treatment method that could potentially turn any metal surface into a rapid bacteria killer – just by giving the metal’s surface a different texture.

Why is surface disinfection important?

Bacteria are responsible for many of the illnesses that make our lives difficult – salmonella, boils, and syphilis are only a few of the myriad types of harm that bacteria can cause to our bodies. One of the annoying things about bacteria is that most of them can survive on metal surfaces for long periods of time. Add that to the fact that most of the things we touch most frequently – doorknobs, bathroom fixtures, car keys – are made of metal, and you have a host of potential pathogens waiting to hop on to your skin.

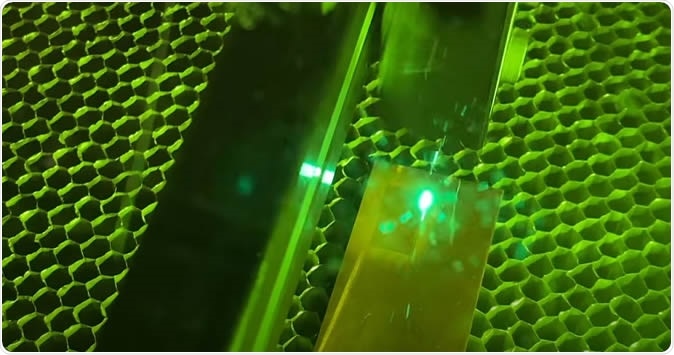

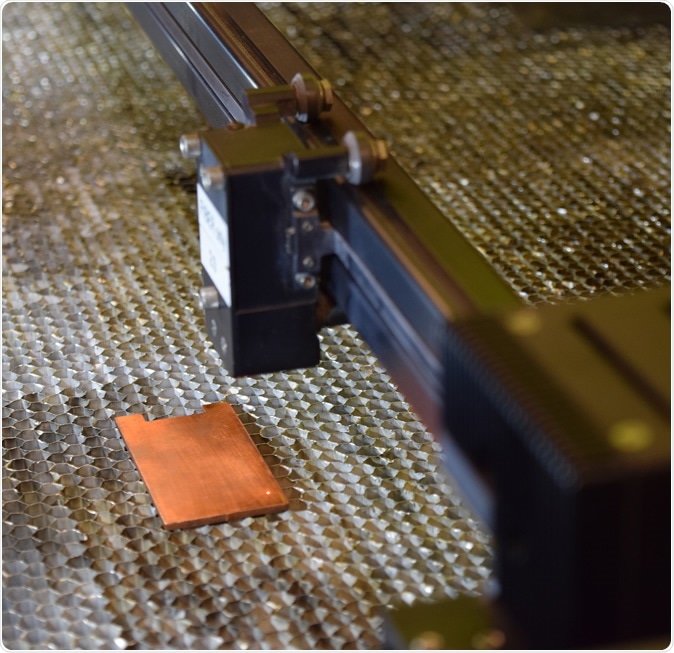

The new process might change all that, transmuting metals from friendly hangout zones to killing fields for bacteria. It works by using a laser to alter the surface texture of the metal. Copper, for example, is often used as a naturally antimicrobial material; however, it takes hours to kill most bacteria on its surface. But with Purdue University’s treatment, the number of bacteria that come in contact and die instantly speeds up dramatically, making it clinically useful.

A laser prepares to texture the surface of copper, enhancing its antimicrobial properties. (Purdue University photo/Kayla Wiles)

Copper typically has a smooth surface. This limits the area of contact with the bacteria, which translates to how many bacteria die. Previously, efforts have been made to use nanomaterial coatings to enhance the surface area of the metal, but these came off very easily and were often toxic.

How laser etching works to kill more bacteria

With the new approach, the technology works with the metal itself. They use a laser to etch nanoscale grooves into the metal, increasing its surface area and enhancing its antibiotic properties. Working with the native metal makes this much sturdier than existing technologies - it doesn’t rub off or hurt the environment.

Treating Metal Surfaces to Kill Bacteria

“The nice thing about our process is that it’s not something we’re adding to the surface,” says Rahim Rahimi of Purdue University’s materials engineering division, “so there’s not any kind of additional material required. There are no antibiotics, no spray coating. It’s just modifying the native surface of the material… “we’ve created a robust process that selectively generates micron and nanoscale patterns directly onto the targeted surface without altering the bulk of the material.” Research is ongoing in using this procedure on alloys that have preexisting antimicrobial properties.

The treated surface has been proven to enhance germ-killing properties – even with aggressive pathogens that have developed resistance to conventional antibiotics such as MRSA. However, the material has not yet been developed to the point where it can eliminate viruses such as those responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, as these viruses are much smaller than bacteria. The etched surfaces have proven effective on both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.

Can it make medical implants safer?

This technology works way beyond making doorknobs more sanitary. However: Rahimi and his team are working on adapting it for use with orthopedic implants and wearable wound patches. Implants are a vulnerable spot in the body’s immune system because of their intrinsically foreign nature. This means extra measures must be taken to protect these infection-prone areas. Usually, antibiotics are used to prevent bacterial biofilm formation, but this can lead to antibiotic resistance in the bacteria.

Purdue University’s laser etching technique can prevent this because of the enormous boost it gives to the antimicrobial nature of the implant surface, without the use of antibiotics or anti-adherence coatings that could slow down the integration of the implant into the body.

Etching the surface of metals with nanoscopic patterns has another benefit: it renders the material much more hydrophilic. Several studies have been done on hydrophilic surfaces and how they aid healing: they have been shown to control inflammation, help bone cells to reattach more strongly, improve the implant’s integration with the body, and contribute to faster osteogenesis, or bone regeneration. Rahimi and his team have observed this behavior in fibroblast cells. Also, when used in wound patches, hydrophilic surfaces help the blood to coagulate more efficiently as well as reducing the potential for infection.

Is laser etching commercially viable?

With its simplicity and scalable nature, the laser etching process pioneered by Purdue University is easy to integrate into the manufacturing practices already in operation for medical devices. Bacteria have ranged from annoyances to life-threatening killers, and huge amounts of a medical team’s work are devoted to keeping them out. Laser etching could provide a useful way to ease this burden considerably.

Source:

Now metal surfaces can be instant bacteria killers, thanks to new laser treatment technique

Journal reference:

Selvamani, V., Zareei, A., Elkashif, A., Maruthamuthu, M. K., Chittiboyina, S., Delisi, D., Li, Z., Cai, L., Pol, V. G., Seleem, M. N., Rahimi, R., Hierarchical Micro/Mesoporous Copper Structure with Enhanced Antimicrobial Property via Laser Surface Texturing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 1901890. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/admi.201901890?_ga=2.35057185.1008137069.1586741252-712945497.1586489343