It is still unclear why some women go into labor for long periods, and some face a high risk of childbirth. Also, some women fall pregnant quickly, while others may take years before they conceive. The answer may be due to a gene inherited from the Neanderthals, an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago.

A team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and Karolinska Institutet in Sweden has found a link between an inherited receptor for progesterone from Neanderthals and increased fertility, fewer miscarriages, and fewer bleeding during early pregnancy.

Neanderthals are ancient people who emerged at least 200,000 years ago during the Pleistocene Epoch. They inhabited Eurasia from the Atlantic regions of Europe eastward to Central Asia. They also went as far as north of Belgium and south in the Mediterranean and southwest Asia. Compared to modern humans, Neanderthals had a more robust build and proportionally shorter limbs.

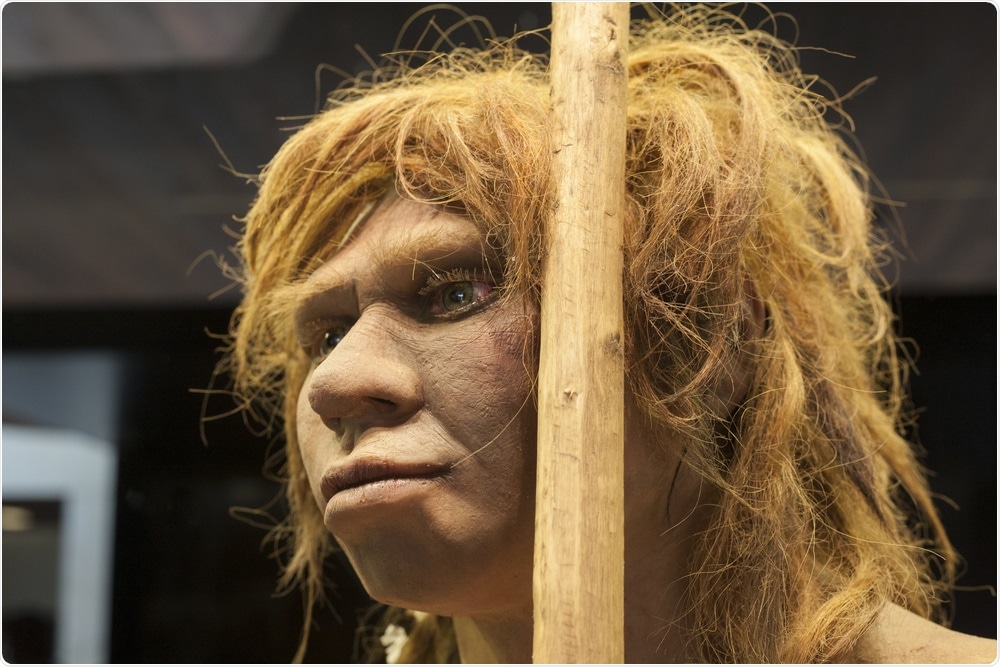

Madrid, Spain - Life-sized sculpture of Neanderthal female at National Archeological Museum of Madrid. Image Credit: J By Juan Aunion / Shutterstock

Role of progesterone

Progesterone is a hormone secreted by the corpus luteum in the ovary during the second half of the menstrual cycle. The hormone plays an essential role in maintaining the early stages of pregnancy.

One of the essential functions of progesterone is to thicken the lining of the uterus each month. When the endometrial lining is enriched, it becomes prepared to receive and nourish a fertilized egg.

One of the essential roles of the human placenta is to produce the steroid hormone progesterone, which is required for the maintenance of pregnancy. Progesterone levels remain elevated throughout pregnancy, helping make the fetus viable until delivery.

Those with low levels of progesterone during pregnancy may experience miscarriages and bleed in the first trimester.

Neanderthal gene variant

In the study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, one in three women in Europe inherited the receptor for progesterone from Neanderthals, a gene variant tied to better fertility, fewer miscarriages, fewer high-risk pregnancies.

The team noted that the Neanderthal gene variants have reached nearly 20 percent frequency in non-Africans and have been linked to preterm birth.

The researchers showed that one of the missense substitutions appears fixed in Neanderthals. They also found that two Neanderthal haplotypes carrying the progesterone receptor (PGR)entered the modern human population. Today, some women carry the gene that expresses higher levels of the receptor.

"The progesterone receptor is an example of how favorable genetic variants that were introduced into modern humans by mixing with Neandertals can have effects in people living today," Hugo Zeberg, a researcher at the Department of Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement.

Study findings

To arrive at their findings, the team analyzed date from the UK Biobank using the Gene ATLAS tool from more than 450,000 participants. Of these, 244,000 are women. The team found that one in three women in Europe has the progesterone receptor. Meanwhile, 29 percent carry one copy of the Neanderthal receptor, and 3 percent have two copies.

"The proportion of women who inherited this gene is about ten times greater than for most Neandertal gene variants. These findings suggest that the Neandertal variant of the receptor has a favorable effect on fertility," Zeberg added.

The study also showed that women who carry the gene variant from Neanderthals tend to have fewer miscarriages, give birth to more children, become pregnant more, and experience fewer bleedings. The team also conducted molecular analyses and found that the women produce more progesterone receptors in the cells, providing increased sensitivity to progesterone. As a result, these women are protected against bleeding and miscarriages.

"In a cohort of present-day Britons, these carriers have more siblings, fewer miscarriages, and less bleeding during early pregnancy, suggesting that the Neandertal progesterone receptor alleles promote fertility. This may explain their high frequency in modern human populations," the team concluded in the study.

Progesterone is crucial in pregnancy as it makes sure the fetus can survive throughout pregnancy. Women with low levels of progesterone may experience miscarriages. Learning more about the gene variant can help clinicians determine women who are at a high risk of first trimester complications.

The research was supported by the NOMIS Foundation and the Max Planck Society.