Researchers in the UK have shown that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is capable of preferentially targeting a wide range of animal species.

This “tropism” for mammalian host cells raises concerns about the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to target wild, companion, or livestock animals that could then become reservoirs for the virus.

The team from the University of Cambridge and the Pirbright Institute found that the Spike protein on SARS-CoV-2 engages with the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) across a wide range of animals, even though the Spike binding site shows a between-species variation in its amino acid composition.

Human ACE2 receptor, illustration Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The findings suggest that several animals could have been the intermediate host that enabled the virus to jump from its original host to humans (zoonosis). They also raise concerns about the potential human-to-animal transmission (reverse zoonosis), which has worrying implications for disease control in people, animal health, and food security.

A pre-print version of the paper is available in the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

Understanding the jump to humans

Since SARS-CoV-2 was identified as the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the virus has infected more than 8.9 million people and caused more than 466,000 deaths.

Given that its genome resembles that of SARS-CoV-1 and other coronaviruses found in bats, SARS-CoV-2 is presumed to have also originated in bats. Along with the pangolin, bats have also been proposed as a potential intermediate host that enabled the jump to humans.

“However, whether the virus spread directly to humans or through an intermediate host is currently unclear, as is the potential for this virus to infect companion animals, livestock and wildlife that could act as viral reservoirs,” writes the team.

Identifying the original host of SARS-CoV-2 and any intermediate hosts would help researchers understand when and where it jumped to humans, which could be important for predicting future risks and preventing further outbreaks of similar or unrelated viruses.

Understanding the host tropism of SARS-CoV-2 beyond its targeting of humans would also help predict the risk of reverse zoonosis.

“However, how widely this host-range or receptor tropism extends and the molecular factors defining atypical transmission to non-human hosts remain the subject of intense investigation,” the researchers say.

The ACE2 binding domain is highly variable

The binding site for SARS-CoV-2 on ACE2 is highly variable, and recent data have shown that SARS-CoV-2 Spike and various other coronavirus Spike proteins bind the same ACE2 domain to gain viral entry.

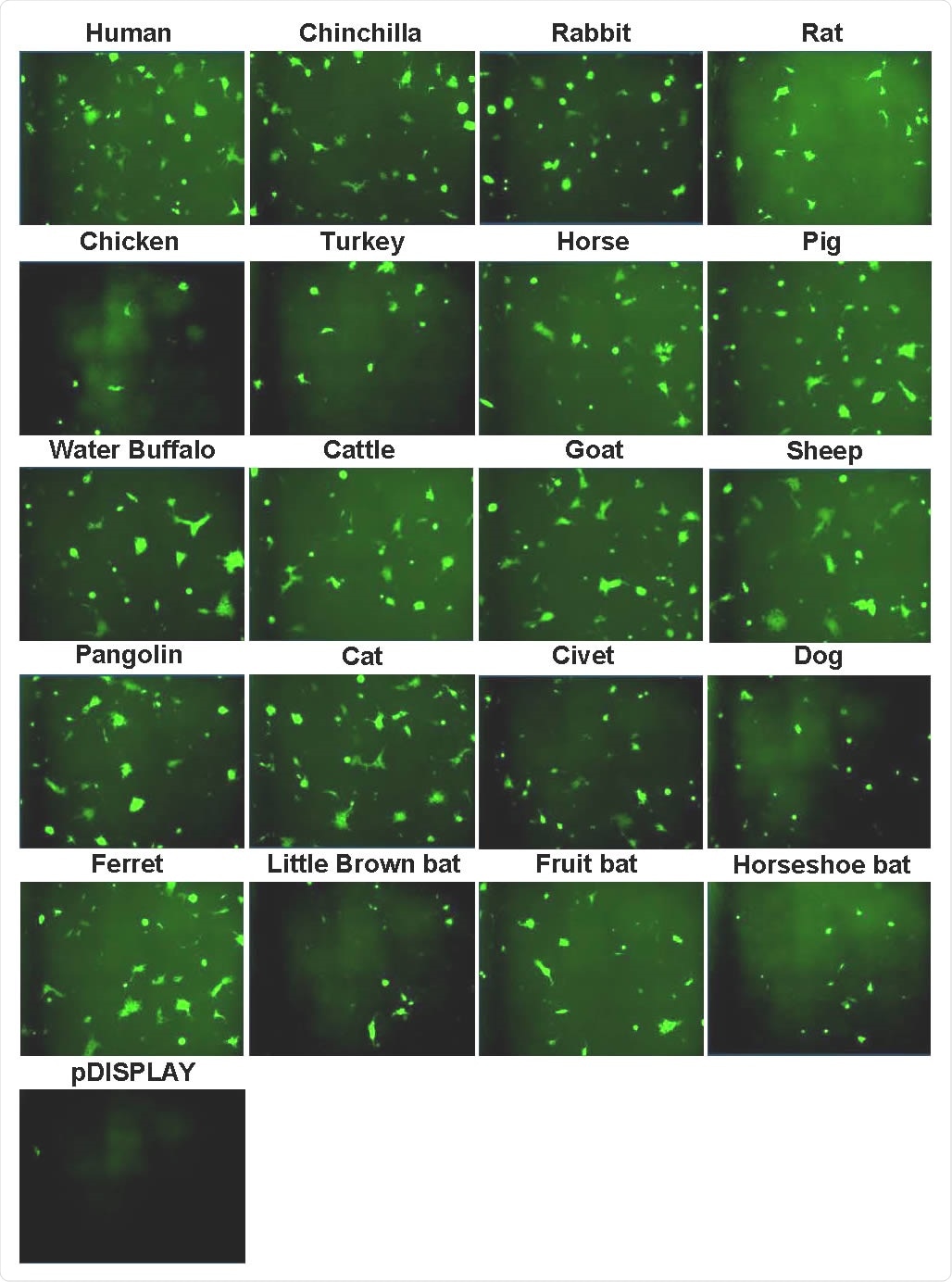

Now, Bailey and the team have used a combination of assays and live virus experiments to analyze interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 isolated from humans and 22 other vertebrate species. The species included companion animals, livestock, bats, and animals that have previously been associated with coronavirus outbreaks, including the pangolin.

The study found that the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein has a relatively broad tropism for ACE2 in animals. Receptors in the dog, cat, rabbit, hamster, horse, pig, sheep, goat, water buffalo, cattle, and pangolin all supported higher levels of viral entry, compared with human ACE2.

In contrast, ACE2 from the chicken, turkey, and all bat species analyzed (horseshoe bat, fruit bat, and little brown bat) supported lower levels of viral entry than human ACE2.

Syncytia formation following SARS-CoV-2 Spike expression. Effector cells expressing half of a split luciferase-GFP reporter and SARS-CoV-2 Spike were mixed with target cells expressing ACE2 proteins from the indicated hosts and the corresponding half of the reporter (see Methods). A vector only control was also included (pDISPLAY). Representative micrographs of GFP-positive syncytia formed following co-culturing are shown. Images were captured using an Incucyte live cell imager (Sartorius).

The Spike protein’s varying utilization of ACE2 receptors

On comparing the hamster and rat, the team found that closely related sequences on ACE2 were used differently by SARS-CoV2 Spike protein. Rat ACE2 did not support viral fusion to the host cell, whereas hamster ACE2 did.

The researchers say they identified five amino acid substitutions in rat ACE2 that would probably reduce Spike RBD binding. The substitutions would stop ACE2 from having the hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and side-chain methyl group needed for it to associate with Spike RBD residues.

“Multiple substitutions are predicted to inhibit Spike binding to rat ACE2 when compared with the closely related hamster protein,” says the team. “Our finding that hamster ACE2 allows entry of SARS CoV-2 indicates this animal is a suitable model for infection,” write Bailey and team.

Another example of differential ACE2 usage was observed among closely-related bat species.

While none of the bat ACE2 supported viral fusion to the same degree human ACE2 did, the Spike protein was far less able to utilize horseshoe bat ACE2 than it was fruit bat and little brown bat ACE2.

The team says all bat ACE2 had substitutions that disrupted viral binding to some degree, but it was a substitution called E30N that probably accounted for the more impaired binding to horseshoe bat ACE2.

“SARS-CoV-2 receptor usage likely shifted”

The authors were surprised to find this lack of tropism for bat ACE2 since studies have previously shown that the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein binds bat ACE2 with high affinity, and the viral origin is widely accepted to be bats.

“The absence of a significant tropism for any of the three genetically distinct bat ACE2 proteins we examined indicates that SARS-CoV-2 receptor usage likely shifted during zoonotic transmission from bats into people, possibly in an intermediate reservoir,” says the team.

More thorough investigation is needed

The authors say the study shows that in addition to human ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 exhibits a broad tropism for mammalian ACE2.

“More thorough investigation, including heightened virus surveillance and detailed experimental challenge studies, are required to ascertain whether livestock and companion animals could act as reservoirs for this disease or as targets for reverse zoonosis,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources