The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused over 9 million deaths and over 472,000 deaths. The rapid and extensive spread of the infection has led to many countries implementing lockdowns and other restrictions on social interactions in an effort to slow the pace of the pandemic.

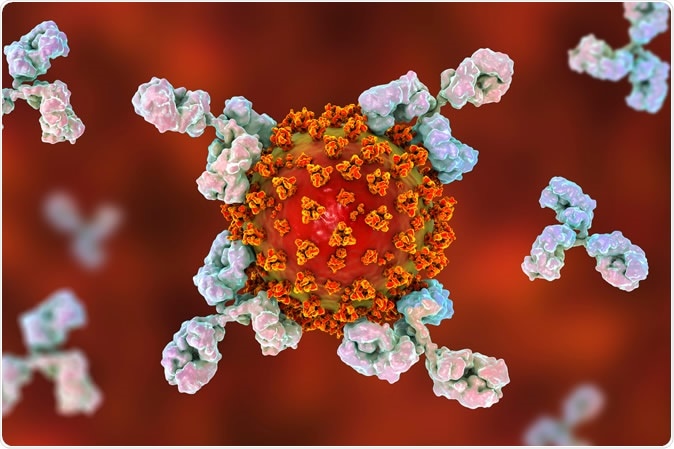

Antibodies attacking SARS-CoV-2 virus, the conceptual 3D illustration. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The Need for Serologic Assays

Currently, diagnosis lags in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) because of the lack of reliable and rapid reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR). However, serologic assays can help with vaccine development, the focused deployment of diagnostic testing, and the use of novel treatment. They may also help to understand the underlying disease process.

The researchers say, “Serological assays increase understanding of disease severity. Their application in regular surveillance will clarify the duration and protective nature of humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2.”

The Current Study: ELISA and RDT

The use of the inexpensive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with RDT designed for LMICs makes this study unique in its applicability to developing regions. The researchers tested 645 clinical samples from 177 patients. About 34% and 35% were white and non-white, respectively. The median age was 64 years, with 57% being male. Almost three-fourth had one or more coexisting illnesses.

34 (19%) were asymptomatic on admission and were diagnosed incidentally. For those with symptoms, there was a median delay of 6 days from the earliest symptom to testing. 94% were hospitalized, and a quarter died at a median interval of 19 days. 61% were discharged by the end of the study after a median hospital stay of 19 days. 14 (8%) were still in hospital when the study ended. 63 (36%) patients needed intensive care.

Among the IgG ELISA results, it is seen that about 9% did not seroconvert throughout the follow-up period. About 7% developed antibodies after enrolling in the study, while 84% had antibodies at the time of the first test.

The follow-up of the patients who did not develop antibodies up to the end of the study period, for another three weeks, shows that between 2% to 9% may fail to seroconvert for weeks despite having the infection.

Predictors of Seroconversion

After seroconversion, the mean IgG values remained constant for up to 2 months from the first symptom. The levels did not change by sex or the presence of respiratory symptoms. However, non-whites had a higher mean IgG titer at 1.06 vs 0.85 in whites.

Seroconverters were older, at a median of 65 years than non-seroconverters, at 41 years, and more likely to have a coexisting disease. Notably, patients with hypertension were more likely to seroconvert, as were those with a higher body mass (BMI).

Rising C-reactive protein (CRP) levels predict a worse outcome due to the cytokine release syndrome. Non-seroconverters had lower CRP values compared to seroconverters. These differences were more pronounced if only peak CRP values were compared. Other markers of inflammation like peak D-dimer, fibrinogen, and ferritin followed the same trend.

The Importance of Serologic Testing in COVID-19

These findings relate to patients who present after being symptomatic for many days and presumably have reduced viral loads. Serological tests can help pick up an infection in later phases of the disease when the RT-PCR is no longer sensitive enough. Again, serological tests can help understand which patients are at risk for infection and their immunity, as well as being immensely useful for epidemiological tests.

The stable antibody levels is another finding of significance, as well as the identification of factors related to seroconversion, namely, hypertension, symptomatic disease, increasing age, and increased BMI. Non-whites, those admitted to hospital, and higher inflammatory marker titers predict higher antibody levels, which in turn predict greater severity of the disease.

This could be because antibody titers and cytokines increase in parallel, signaling a higher risk of severe disease and death. Or on the other hand, it may be because the innate immune response is more robust in these individuals, with a resulting increased risk of severe disease and death. This could, of course, be due to a higher viral load or the activation of genes that regulate innate immunity.

However, higher viral loads are expected to stimulate acquired immunity, and this is more likely given the benefit shown with passive antibody therapy in small trials.

Why Some Do Not Seroconvert

The 9% of patients who are non-seroconverters may truly never develop antibodies or may develop other forms of immune response such as T cell immunity or antibodies confined to other antigens. Again, very mild infections may involve only the respiratory mucosa, with dominant secretory immune responses, as a result, and, therefore, limited systemic IgG antibody production.

Implications and Importance of the Study

The study shows that many patients with COVID-19 remain seronegative for weeks after infection, and a proportion up to 60 days later is still negative for antibodies. This is the first such study outside China and shows how different races react to the infection. The advantages include the use of this first-generation ELISA assay to confirm infection purely on serological grounds, in a diverse group, and with infection at different phases from asymptomatic to fatal infection.

The use of serological testing enhances diagnostic accuracy, especially when RT-PCR is negative, but symptoms suggest COVID-19. This may be a valuable procedure when late presentation becomes more prevalent, perhaps due to containment measures that lead patients to self-isolate rather than come to hospital.

The investigators sum up: “Serological testing, and the ability to detect viral antigens, may increase diagnostic accuracy for COVID-19 and our findings support early studies suggesting that these diagnostic modalities should be combined, particularly when RT-PCR results are negative but symptoms resemble those of COVID-19.”

The study has some limitations, such as the inclusion of only hospitalized patients, with about 20% being asymptomatic. Patients with mild infection must also be included in future studies, which will also address the association between the viral load as measured by RT-PCR and serological response, as well as the duration of antibody production. Finally, the clinical contribution of antibody responses in the recovery or protection from this infection requires more intensive study.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources