Severe cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2, were recently linked to considerable lung damage and the occurrence of infected multinucleated syncytial pneumocytes. In a nutshell, syncytium is a large cell-like structure that arises when many cells fuse.

Cell entry prompting cell fusion

SARS-CoV-2 cell entry is instigated by interactions between the spike glycoprotein and its receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). This is followed by the cleavage of spike glycoprotein and priming by the cellular protease TMPRSS2 (or other proteases).

Nonetheless, the interferon-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3) halt many viruses at the entry-level by effectively inhibiting virus-cell fusion at pore formation stages.

Alongside fusion mediated by the infective virions, spike proteins at the plasma membrane can trigger receptor-dependent syncytia formation. These syncytia have been previously observed in infections with SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, or SARS-CoV-2, but they were not adequately characterized.

Furthermore, the viral and cellular mechanisms responsible for regulating the formation of these syncytia are not well understood. One hypothesis is that they are stemming from direct infection of target cells, or as a result of the indirect immune-mediated fusion of myeloid cells.

A research group from Institut Pasteur and CNRS-UMR3569 in Paris, as well as from Vaccine Research Institute in Créteil, France, decided to shed more light on this important problem by delineating mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-induced cell-to-cell fusion and elucidating how exactly IFITMs and TMPRSS2 impact syncytia formation.

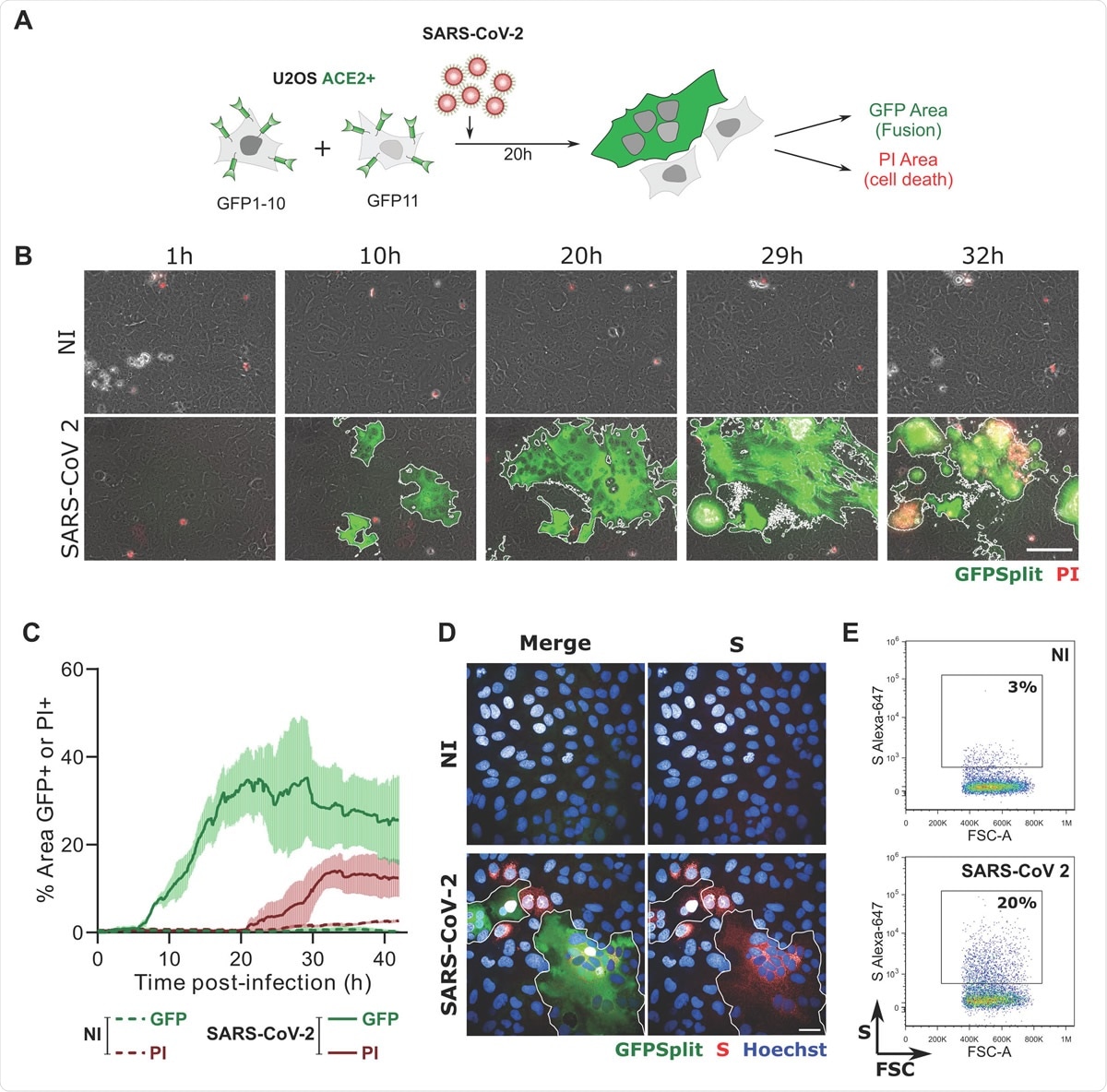

SARS-CoV-2 induced syncytia formation. A. GFP-Split U2OS-ACE2 were co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio and infected with SARS-CoV-2. Syncytia formation and cell death was monitored by video microscopy or at endpoint using confocal microscopy and high content imaging. B. Still images of GFP (syncytia) and Propidium Iodide (PI) (cell death) at different time-points. Scale bar: 100 μm. C. Quantification of U2OS-ACE2 fusion and death by time-lapse microscopy. Results are mean±sd from 3 fields per condition. D. S staining of infected U2OS-ACE2 cells analyzed by immunofluorescence. The Hoechst dye stains the nuclei. Scale bar: 40 μm. E. Surface S staining of infected U2OS-ACE2 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Infecting cell lines, expressing proteins

The researchers first appraised whether SARS-CoV-2 infected cells may actually form syncytia. This was done by utilizing U2OS bone osteosarcoma cells expressing a stable ACE2 receptor. This cell line was selected due to its flat shape, which in turn facilitates imaging.

"We then asked whether TMPRSS2 and IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 impact syncytia formation", study authors further explain their research approach. "We generated S-Fuse cells stably producing each of the four proteins," they add.

Their expression was subsequently verified by either flow cytometry or Western blotting. Combining these two methods represents an optimal approach since Western blotting shows limited capability for multiparameter quantitative analysis.

Finally, the researchers assessed whether other cell types also form syncytia upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mechanisms of fusion and its regulation by IFITMs and TMPRSS2 were characterized in depth.

Syncytia produced by SARS-CoV-2 infected cells

"Here, we show that SARS-CoV-2 infected cells express the viral spike protein at their surface and fuse with ACE2-positive neighboring cells", explain study authors. "The expression of spike protein without any other viral proteins triggers syncytia formation," they add.

But although some cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 form large syncytial structures, this was not observed in all cell cultures. Hence, it can be concluded that syncytia formation represents a cell type-dependent process likely reliant on a different set of parameters.

The researchers have further demonstrated that TMPRSS2 can significantly accelerate SARS-CoV-2-mediated cell-to-cell fusion. Such fusogenic activity is seen in other coronaviruses as well (i.e., SARS-CoV-1, HCoV-229E, and MERS-CoV).

On the other hand, IFITMs are shown to inhibit S-mediated fusion, with IFITM1 being much more active than IFITM2 and IFITM3. More specifically, IFITM proteins alter the rigidity of cellular membranes to halt the fusion process.

A frequent occurrence – but what does it mean?

"It will be worth determining which structural changes are triggered by TMPRSS2 on the viral protein and its receptor, and how these changes may affect the relative affinities of the two proteins and the dynamics of the fusion process", emphasize study authors.

And indeed, the way how TMPRSS2 thwarts the inhibitory activity of IFITMs on syncytia formation mediated by SARS-CoV-2 raises intriguing questions. However, this observation is not unprecedented, since two other coronaviruses (human HCoV-229E and one from bats) also utilize proteolytic pathways in order to break away from IFITM restriction.

In any case, the analysis of 41 samples from patients who died of COVID-19 revealed the presence of extensive alveolar damage and large multinucleated lung cells expressing viral RNA and proteins in basically half of those individuals.

Therefore, syncytia can be considered as a frequent occurrence in severe COVID-19. Now, the research has to appraise whether it is also generated in mild cases, and are there polymorphisms in IFITMs highly characteristic for only critical cases (since something similar is seen with influenza virus).

These results definitely open the door for future assessment of the importance of syncytia in viral dissemination and persistence, the disintegration of alveolar architecture, as well as inflammatory and immune responses in COVID-19.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources