Cases of pet animals contracting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been reported since the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) first emerged. Now, a pet cat has become the first animal in Britain to test positive after contracting the virus from its owners.

The cat developed symptoms of shortness of breath. The pet owners took it to a veterinary clinic, where it was initially suspected to have feline herpesvirus, a common respiratory infection in cats.

A sample from the cat tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 as part of a research program at the University of Glasgow Center for Virus Research. This program aims to screen hundreds of samples for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the country’s cat population. The test was performed at the Animal and Plant Health Agency in Weybridge, Surrey, on July 22.

Human ACE2 receptor, illustration Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Reverse zoonosis

Health experts say that the case is the first known human to feline transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the country, but this does not mean the infection is being spread to people by their pets.

Zoonosis is described as viral infections that jump from animals to humans, just like coronaviruses, which are mainly found in wild animals like bats, camels, and civet cats, among others. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) were reported to have come from civet cats and camels. The current coronavirus pandemic has been claimed to come from pangolins, which contracted the infection from bats.

Pangolin. Image Credit: 2630ben / Shutterstock

On the other hand, reverse zoonosis is when a virus first infects humans and then jumps to animals. Since the emergence of the novel coronavirus pandemic, reports of infections were reported in pet dogs in Hong Kong and even in a tiger in a zoo in the United States.

Siberian "Amur" tiger in the Bronx Zoo. Image Credit: Vladimir Korostyshevskiy / Shutterstock

Spread from people to animals

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that it is still unknown where the current coronavirus disease came from but said it might have originally come from an animal, like a bat.

“At this time, there is no evidence that animals play a significant role in spreading the virus that causes COVID-19. Based on the limited information available to date, the risk of animals spreading COVID-19 to people is considered to be low,” the CDC said.

The health agency added that more studies are needed to shed light on how different animals could be affected by COVID-19. As scientists race to learn more about the virus, it appears that it can spread from people to animals in some situations.

“We are still learning about this virus, but it appears that it can spread from people to animals in some situations, especially after close contact with a person sick with COVID-19,” the CDC explained.

The CDC also explained that cats, dogs, and a few other types of animals could be infected with the novel coronavirus. However, it says that experts don’t know all of the animals that can be infected.

Animals and COVID-19

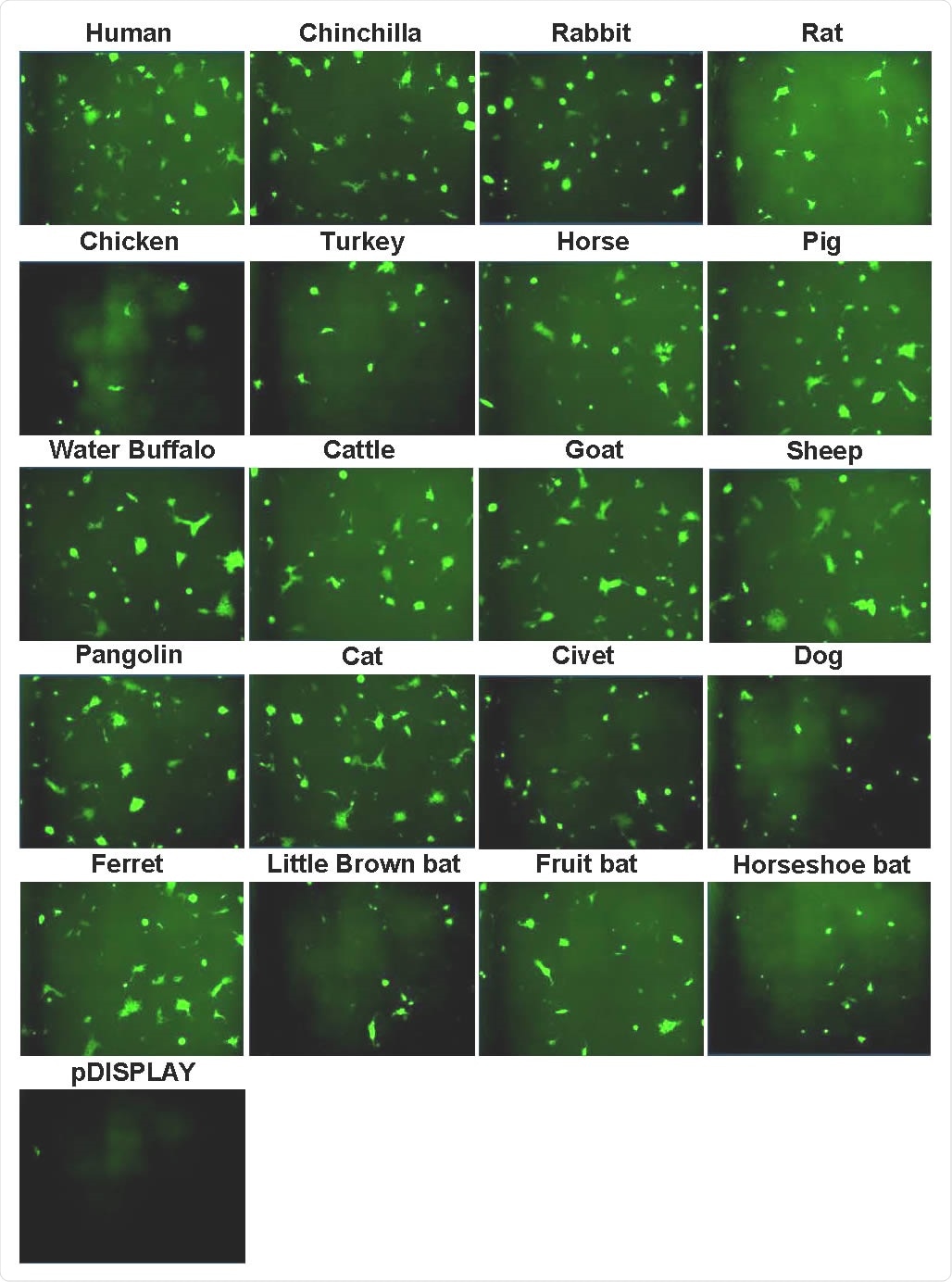

Three previous studies have tackled the risk of animal infection with SARS-CoV-2. In a study by researchers in the United Kingdom, the novel coronavirus can infect a wide range of animal species, including dogs, cats, hamsters, rabbits, horses, goats, pigs, water buffalos, sheep, cattle, and pangolins. These animals showed higher levels of viral entry.

Syncytia formation following SARS-CoV-2 Spike expression. Effector cells expressing half of a split luciferase-GFP reporter and SARS-CoV-2 Spike were mixed with target cells expressing ACE2 proteins from the indicated hosts and the corresponding half of the reporter (see Methods). A vector only control was also included (pDISPLAY). Representative micrographs of GFP-positive syncytia formed following co-culturing are shown. Images were captured using an Incucyte live cell imager (Sartorius).

Meanwhile, animals like turkey, chicken, and all bat species supported lower levels of viral entry than human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

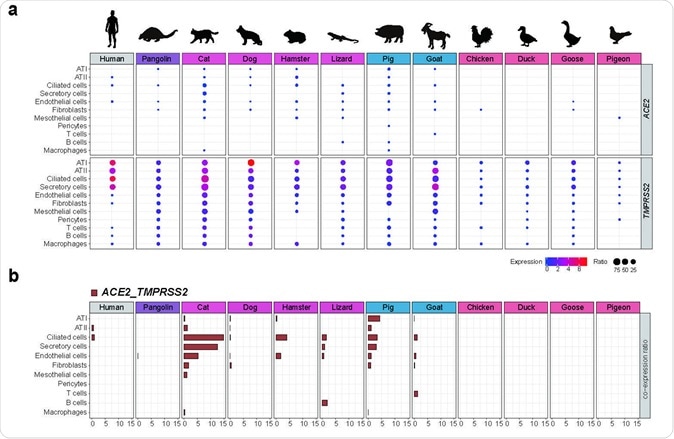

Another study uploaded in BioRxiv has identified SARS-CoV-2 target cells in distinct tissues of cat, hamster, and pangolin. The most notable finding was that the SARS-CoV-2 target cells were the higher proportion of SARS-CoV-2 target cells in cats.

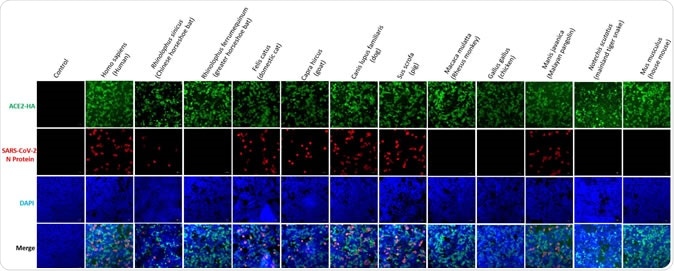

Lastly, scientists at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said that SARS-CoV-2 was able to engage ACE2 receptors across a wide range of animal species, such as the horseshoe bat, domestic cat, dog, pig, goat, and Malayan pangolin.

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 of HEK293T cells conferred by different 2 species of ACE2. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing 3 indicated ACE2. Cells were infected with 0.5 MOI of SARS-CoV-2 24 h after the 4 transfection, and were detected for the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by IFA.

Understanding zoonosis and reverse zoonosis in the coronavirus pandemic may help scientists study the behavior of the virus, and the chances of transmission by animals, which can make containing the virus spread more difficult.

The case toll of the coronavirus pandemic has now topped 16.48 million, with a death toll of more than 654,000.