The study showed that the animals, which are kept in their millions on commercial farms across China, are susceptible to infection and readily transmit the virus to other raccoon dogs in close proximity.

Animals that were intranasally inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 quickly became infected and went on to transmit the virus to direct contact animals.

“With China’s substantial contribution to the global fur production of > 50 million animals per annum, it is conceivable that raccoon dogs may have played a hitherto unexplored role in the development of the pandemic,” write Thomas Mettenleiter and colleagues.

The findings support the implementation of adequate surveillance and risk mitigation strategies for both farmed and wild raccoon dogs, they add.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

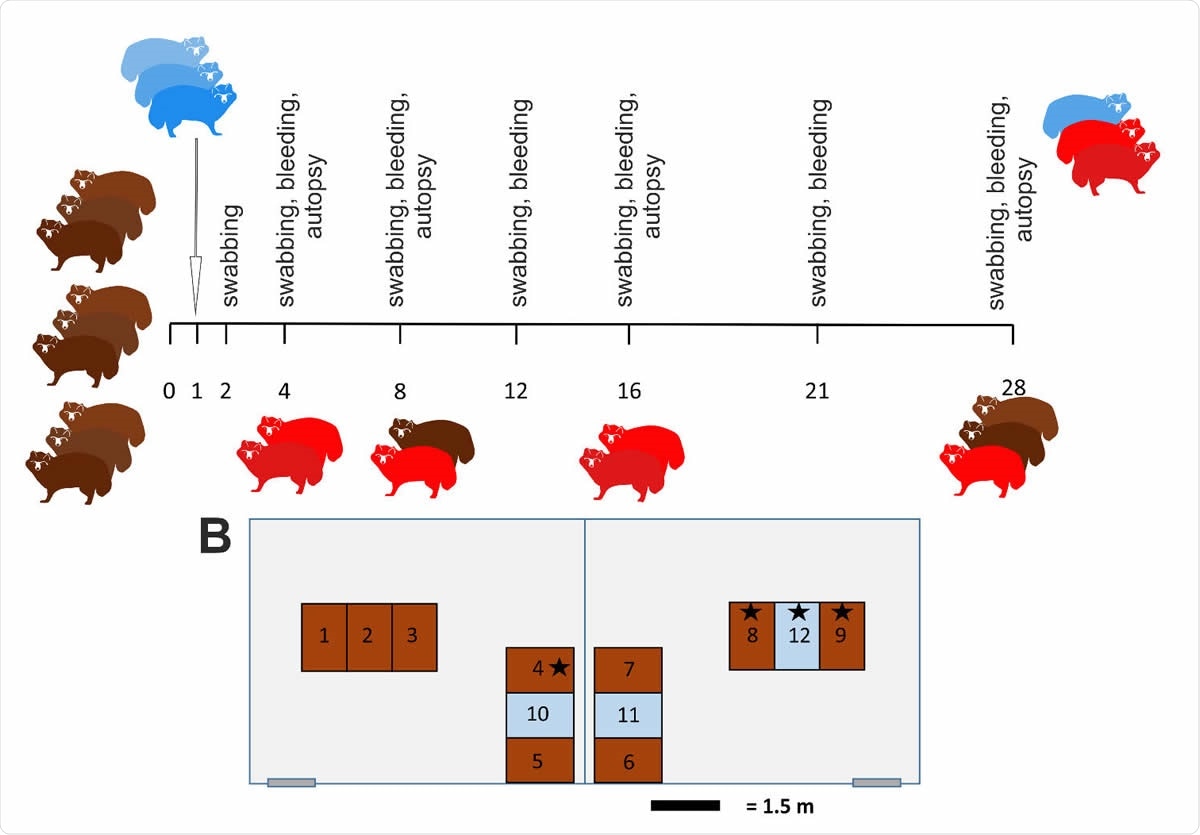

Study design ( 422 A) Outline of the in vivo experiments with an observation period of 28 days. Animals (n=9) were inoculated intranasally with 105 TCID50/ml and three naïve direct contacts were added 1 dpi. On day 4 (animals #1, #2), day 8 (#3, #4), and 12 (#5, #6) two raccoon dogs each were sacrificed and subjected to autopsy. All remaining animals were euthanized on day 28 pi. Animals that became infected are highlighted in red. (B) Arrangement of the individual cages for the raccoon dogs in two separate rooms of the BSL 3 facility at the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut. Inoculated animals (brown), contact animals (blue) and animals that remained uninfected ( ) are indicated.

Potential intermediate hosts

Since the first cases of COVID-19 were identified in Wuhan, China, late last year, SARS-CoV-2 has swept the globe and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11th, 2020.

Viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 have been identified in bats, but whether the virus was directly transmitted from bats to humans or whether transmission involved an intermediate host such as the pangolin remains unclear.

In the cases of SARS-CoV-1 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), intermediate hosts were eventually found to be involved, but no such intermediary has yet been confirmed for SARS-CoV-2.

Although the pandemic has been driven by transmission between humans, cases of human-to-animal transmission through contact with companion animals and on mink farms have been reported.

“Increasing evidence supports the potential of several carnivore species to become infected by SARS-CoV-2 as a result of anthropo-zoonotic transmission, possibly leading to re-infections of humans,” say Mettenleiter and team.

Natural SARS-CoV-1 infection of raccoon dogs has been documented, suggesting the animals’ potential involvement in the 2002-2003 outbreak. Furthermore, some studies have shown that in raccoon dogs, the host cell protein angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) serves as an efficient receptor of both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2.

However, to date, there are no known studies that have investigated the infection of raccoon dogs with SARS-CoV-1 or SARS-CoV-2 under controlled conditions and with serologic surveillance.

What did the current study involve?

Now, Mettenleiter and colleagues have tested susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in raccoon dogs by infecting nine animals with the virus and then evaluating viral transmission by introducing three further animals 24 hours post-infection.

Prior to the experiment, all animals tested negative for the virus by a reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction and antibody tests. Nine raccoon dogs (3 males, 6 females) were inoculated intranasally with 105 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 2019_nCoV Muc-IMB-1.

Nasal, oropharyngeal, and rectal swabs were taken on days 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 21, and 28 following infection and blood samples were taken on days 4, 8, 12, 16, 21 and 28.

What did the study find?

Six of the original nine animals became infected with SARS-CoV-2. The animals had already started to shed viral RNA in nasal and oropharyngeal swabs at two days post-infection, and infectious virus was isolated from individual animals up to 4 days post-infection.

Viral RNA was present in the nasal swabs up to 16 days following infection, with the highest viral genome loads found in nasal swabs, followed by oropharyngeal swabs and then rectal swabs.

The virus was transmitted to two of the three contact raccoon dogs that were introduced; one dog tested negative due to its cage neighbors not shedding the virus following infection.

None of the animals exhibited any apparent signs of infection, and at autopsy, no gross lesions that could be attributed to SARS-CoV-2 were observed.

However, histopathology analysis revealed mild rhinitis in three animals by day four, in one animal by day eight and in another animal by day 12.

“Except for mild rhinitis associated with the presence of viral antigen in the nasal mucosa, no other infection-related histopathological changes were observed,” says the team.

The serological analysis showed that by day 8 following infection, all animals had antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 and two of the inoculated animals had neutralizing antibodies

Testing for viral mutations

To test whether any viral adaptations had occurred during infection, the team performed high throughput sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 re-isolated from nasal swabs of one inoculated dog and one infected contact dog. The re-isolated virus was identical to the inoculum, showing that no mutations had occurred and suggested that the virus is already sufficiently adapted to this potential host.

“Rapid, high-level virus shedding, in combination with minor clinical signs and pathohistological changes, seroconversion and absence of viral adaptation highlight the role of raccoon dogs as a potential intermediate host,” writes the team.

The researchers say affected fur farms may serve as reservoirs for SARS- CoV-2 and that this risk should be mitigated by efficient and continuous surveillance.

They also say that while it may be possible to control the virus in holdings, a spill-over into susceptible wildlife species and particularly free-living raccoon dogs would be an even greater challenge for elimination.

“Our results support the establishment of adequate surveillance and risk mitigation strategies for kept and wild raccoon dogs.,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources