Researchers in the United States and Canada warn that more attention needs to be paid to the role that structural variants and recombination in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have played in the evolutionary history of the virus.

The team, from Stanford University, McMaster University, and the University of Texas, say research into the evolutionary dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 - the agent that causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19) - has mainly focused on single nucleotide polymorphisms.

However, to improve reconstructions of SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary history, the relationship between structural variation and recombination in the virus needs to be better understood, say the researchers.

The team has now cataloged more than 100 structural variants in the SARS-CoV-2 genome - mutations that have so far been overlooked.

The researchers have also provided vital pieces of evidence to support that these insertion or deletion mutations (indels) are, in fact, artifacts of recombination and that the SARS-CoV-2 genome contains several template switching hotspots.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

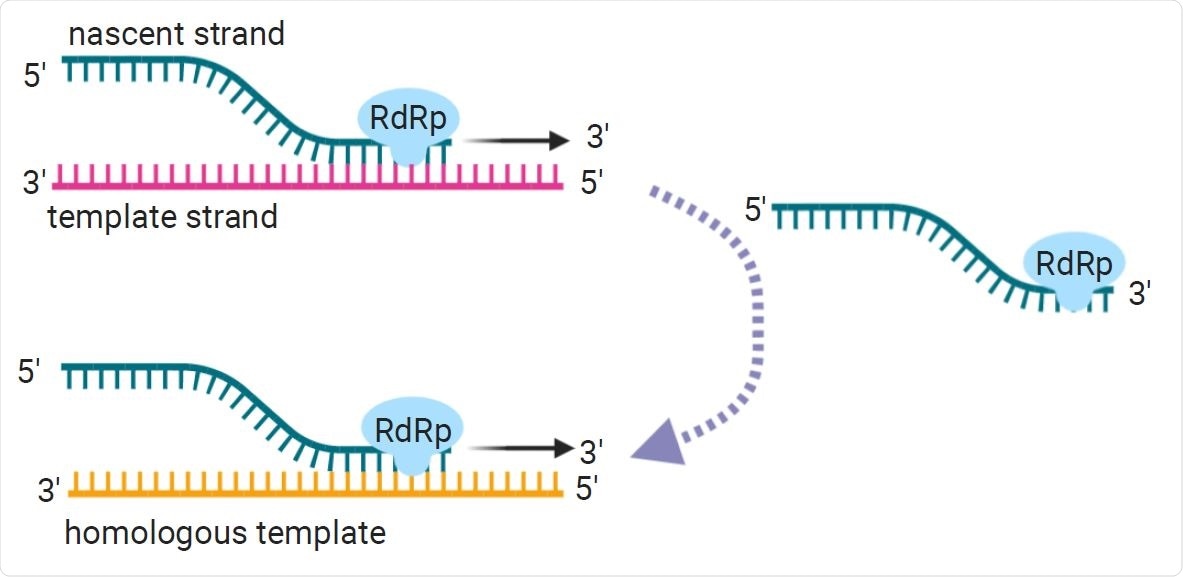

Copy-choice recombination is the presumed primary recombination mechanism for RNA viruses. During negative strand synthesis, the replication complex and the nascent strand disassociate from the template strand. From there, the replication complex can template-switch, or reassociate with a homologous or replicate template strand.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Scientists have tried to find the source of SARS-CoV-2 since the outbreak began

Researchers around the world have been closely monitoring the evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2 and searching for potential sources of the virus ever since the COVID-19 outbreak first began in Wuhan, China, late last year.

“By studying the mutational patterns of viruses, we can better understand the selective pressures on different regions of the genome, the robustness of a vaccine to future strains of a virus, and geographic dynamics of transmission,” said Dennis Wall (Stanford University) and colleagues.

For the majority of evolutionary analysis, a phylogenic tree is built based on mutations that have been observed in the various lineages of SARS-CoV-2. Most of the mutations used are single nucleotide polymorphisms since structural variants are considered potential artifacts of low-quality reads or low-coverage genomic regions during sequencing.

However, this approach means the role of structural variants is overlooked, despite their known involvement in the evolution of viruses and despite the importance of including all types of mutation when constructing an accurate phylogenic tree.

Furthermore, the resulting phylogenic trees are generally non-recurrent and do not account for potential recombination taking place between viral lineages.

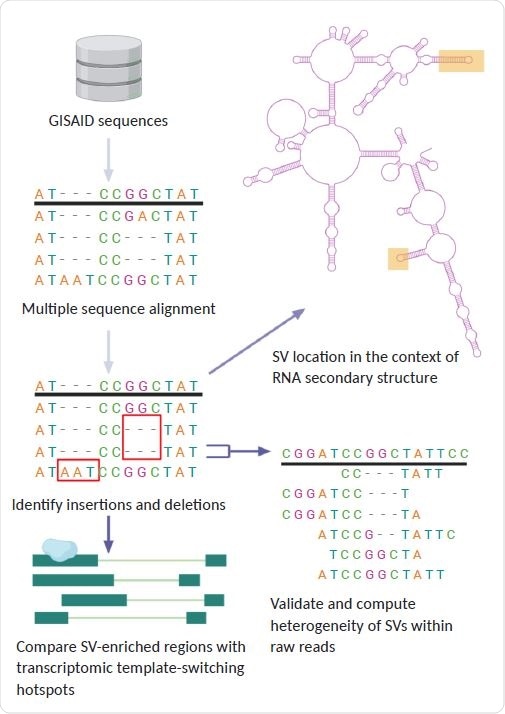

General pipeline of project: using GISAID sequences, we identified structural variants present in SARS-CoV-2 lineages. We compared the location of these SVs to regions of discontinuous transcription breakpoints, computed the heterogeneity of SVs using raw reads, and analyzed the SV locations with respect to the secondary RNA structure using a simulation of the folded SARS-CoV-2 RNA molecule.

Previous studies have generated inconsistent results

Some studies have tried to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 lineages have already recombined, but the findings have been inconsistent.

The comparatively small number of mutations that have occurred in the evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2 presents a challenge when trying to identify a recombined lineage. Furthermore, a lack of publicly available raw reads makes it challenging to determine whether any recurrent mutations are the result of recombination, site-specific hypermutability, or sequencing error.

It is generally considered that recombination in RNA viruses occurs through a copy-choice mechanism by which an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) switches template strands during negative-strand synthesis.

However, “outside of known transcription regulatory sites, what causes RdRp to disassociate and reassociate to a different template strand mid-transcription or replication is not well understood,” said Wall and team.

What did the current study find?

Now, using 16,419 sequences from the GISAID database, the researchers have characterized more than 100 indels that have arisen during the evolution of SARS-coV-2 since June 2020.

The team proposes that these structural variants are the result of imperfect homologous recombination between SARS-CoV-2 replicates and that these clusters of indels indicate that the virus contains several recombination hotspots.

The researchers offer four separate pieces of evidence to support their hypothesis.

Firstly, the structural variants from the consensus GISAID sequences are found in clusters at specific regions across the SARS-CoV-2 genome.

Secondly, long-read transcriptomic data showed that these clusters correspond to genomic regions where rates of transcription regulatory site (TRS)-independent polymerase jumping are high – sites that are presumably hotspots for RdRp template switching.

Thirdly, within raw reads, these structural variant hotspots have high rates of both intra-host heterogeneity and intra-host homogeneity, suggesting that the indels are the result of both de novo recombination events within a host and artifacts of recombination that had occurred previously.

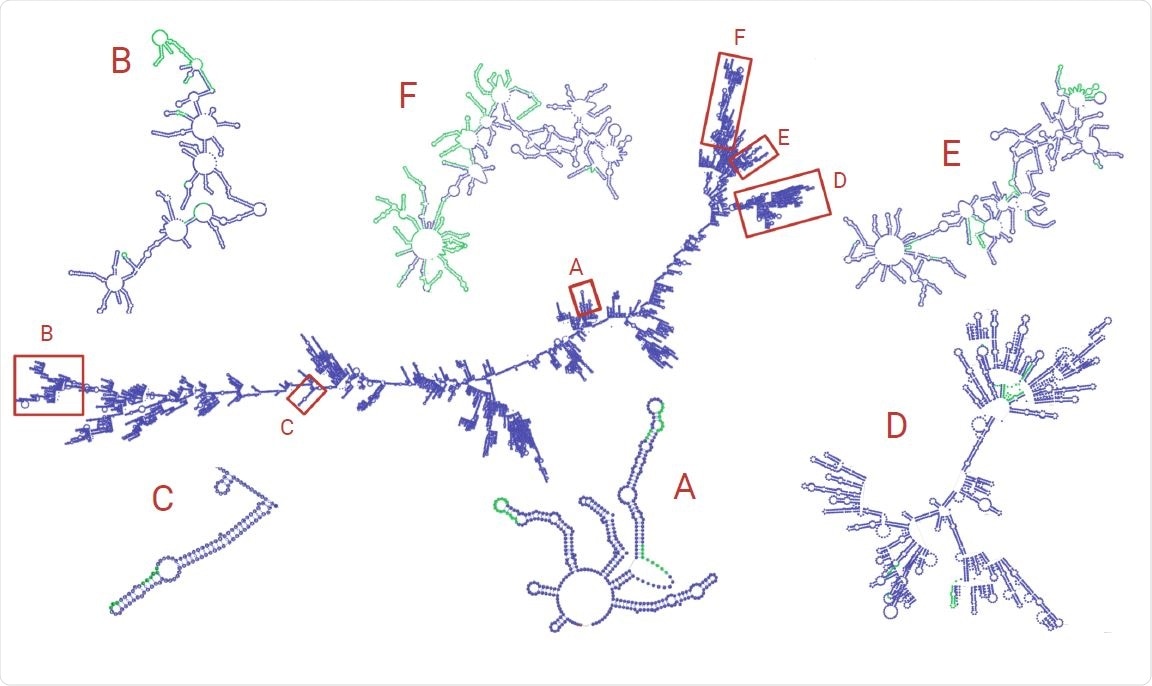

Finally, within the predicted RNA secondary structure of the virus, the clusters of structural variants occur in “arms” of the folded RNA, indicating that global secondary structure may provide a mechanism for RdRp template-switching in SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses.

RNA structure was simulated using RNAfold and visualized with VARNA. The zoomed-in subsections of RNA are from the selected regions of both high SV and discontinuous transcription breakpoint enrichment. Green areas represent regions with an indel. Note that the structures zoomed-in subgenomic RNAs have been manually refined to avoid overlap of loops for easier visualization.

An improved understanding of structural variation is needed

“An improved understanding of structural variation as well as recombination in coronaviruses will improve phylogenetic reconstructions of the evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses,” say the researchers.

It will also bring us “one step closer to understanding the outstanding questions surrounding the RdRp template switching mechanism in RNA viruses,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Wall D, et al. Structural Variants in SARS-CoV-2 Occur at Template-Switching Hotspots. bioRxiv 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.01.278952

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Chrisman, Brianna Sierra, Kelley Paskov, Nate. Stockham, Kevin Tabatabaei, Jae-Yoon Jung, Peter Washington, Maya Varma, Min Woo Sun, Sepideh Maleki, and Dennis P. Wall. 2021. “Indels in SARS-CoV-2 Occur at Template-Switching Hotspots.” BioData Mining 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-021-00251-0. https://biodatamining.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13040-021-00251-0.