The COVID-19 pandemic has led to many different government interventions, including devolving responsibility for health on to individuals chiefly, as in Sweden, to complete lockdown as in China. The combined impact of the pandemic and these non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) has taken a heavy toll on society, and this has led to much discussion as to the relative merits of these measures. A recent study published on the preprint server medRxiv* in September 2020 shows that public trust is vital for the success of any such intervention.

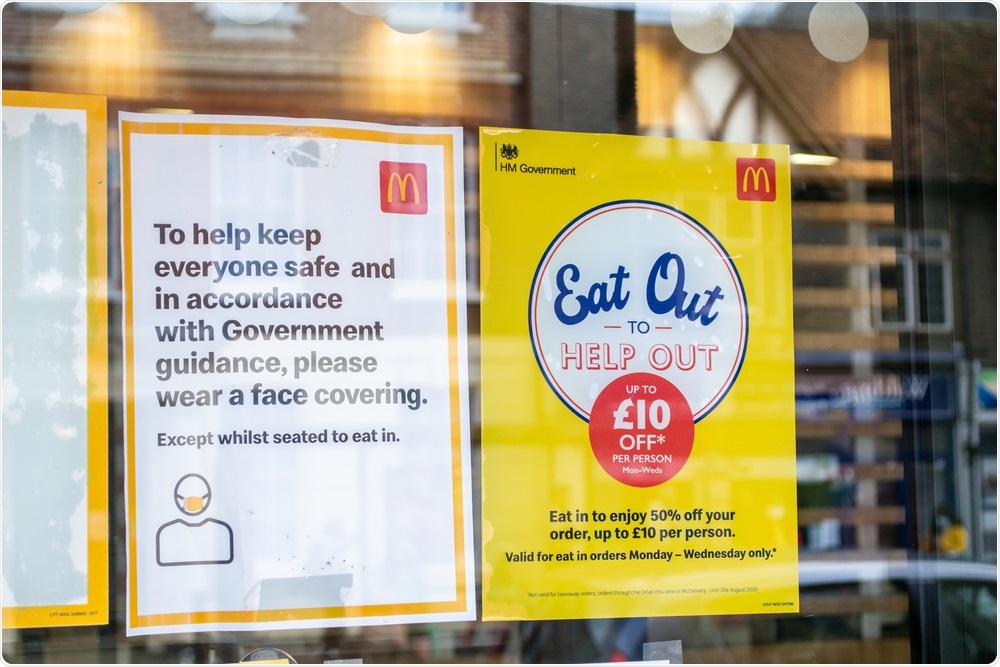

Study: Trust and Transparency in times of Crisis: Results from an Online Survey During the First Wave (April 2020) of the COVID-19 Epidemic in the UK. Image Credit: Jessica Girvan / Shutterstock

Trust is dependent on both past histories of similar measures and the way the people affected perceive the authorities behind these decisions in light of past socioeconomic, social, and historical issues. However, it is also an asset that can be built up, most notably by transparency, as shown during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa over 2014-2016. Here, the healthcare and responder team showed the effects of various attitudes and responses, such as “openness, accountability and reflexivity’, seen by responding to the grassroots realities with confidence-building measures.

The current study by researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and University College London aims to uncover the way trust levels change, as well as the factors that influence public acceptance of these interventions. This depends on the proper communication of risk and the recruitment of the community into these measures. Building trust to accept and participate in both economic and social losses by making recommended or mandated behavioral changes is thus key to managing this pandemic successfully.

In the UK, following the first case on January 29, 2020, the pace of restrictions stepped up progressively until a nation-wide lockdown was declared on March 23, 2020. This was then followed in two days by the Coronavirus Act 2020, conferring specific powers to police to enforce the lockdown.

The current study includes a survey over the acute phase of the lockdown, in April 2020, with rising infection and death numbers while strict measures were being implemented.

What Causes Mistrust in Response Measures?

Recent research has shown that in such an outbreak, trust is not an absolute measure but changes with the sociopolitical setting and the type of epidemic. The researchers in this study, therefore, examined how far people in the UK perceived the government’s response to be effective, and how this was linked to their evaluation of its transparency in making accurate pandemic information available to them.

They used four survey questions crafted to cover this area, as discussed below.

- “Do you think the government is making good decisions about how to control COVID-19?”

- “Do you think that the government cares more about people and their health or the economy?”

- “Do you think the government tells you the whole truth about coronavirus and COVID-19?” and “Briefly describe what it is that you think the government is not being fully truthful about.”

- “Do you think that it is acceptable for governments to force some people to change their behaviors in order to control COVID-19?”

The Participants

Over 9,000 people over 20 years of age responded to the survey, but almost 80% were female and aged 35 to 69 years. About 60% had studied at university, and over 95% were white.

The Response

About half the group said they thought the government was dealing well with the pandemic, but the odds were 30% lower in Scotland compared to London residents. People living in the East, South East, and the West Midlands of England all showed greater trust in the governmental measures.

The higher the level of education, the lower the trust level was, as also with males and younger adults.

Almost 97% said they agreed that some would rightly have to be forced to make behavioral changes to contain the virus.

Concerning the second question, people in Scotland and Northern Ireland had twice the odds of negative response as to whether the government was trying to protect their health rather than the economy compared to those in London. However, people in the East Midlands, South East, and West Midlands all had a more positive response to this query than Londoners, by about 30%.

People under 70 years of age were more likely to feel that the economy was the priority rather than their health, similar to more educated people vs. those who had passed their O-levels or GCSEs (30% to 50% more risk of distrust in governmental priorities). Those with one or more degrees or who had only primary education had over twice the odds of such distrust. Again, with higher income, people were likely to say that the government had a higher priority for the economy compared to health.

The responses to the first two questions were strongly related, at ~60% agreement between perceiving government decisions as poor and government priorities as being economic. Only 5% of those who disagreed with government policy thought their health was the priority. A quarter thought the government had a balanced policy.

Among those who approved of government decisions, a tenth perceived economic health as being the top priority of the government, a third thought the government was about people’s health, and about half thought the approach was balanced between the two.

Only slightly more than a third believed the government mostly was truthful, while ~6% thought they always told the truth. Of this latter group, the odds that they approved of government pandemic measures were doubled. In contrast, those who believed the government always lied or lied most of the time typically disapproved of government decisions as well.

Sub-Themes of Mistrust

This type of analysis was used to evaluate responses with the most negative perception of government truthfulness and from those who were least well-disposed to government handling of the pandemic. These responses came from devolved nations, those with the lowest and highest educational attainments, and those with the lowest and highest incomes.

These were then further assessed to find the differences between groups and how trust developed or was lost among them. They found five significant subthemes, namely,

- Justifying government opacity based on the need to hide some information, either to avoid public panic, to keep things simple and maximize public compliance with the measures, to tailor information to the level of understanding, and because of the lack of scientific consensus or assurance.

- Mistrust of the Government overall because of past negative assessments, especially among poorer sections who have experienced negative impacts of cost-cutting measures and of reduced National Health Service (NHS) expenditure. This was also obvious among Scotland residents, for instance, who thought their own government to be both more transparent and more competent, and among the Welsh who reacted bitterly based on past governmental ‘wrongs.’ The few Northern Irish participants suggested that Brexit had distracted the government from a proper planned response.

- Evidence-based decisions – many participants thought that decisions were not always clearly based on scientific evidence, with some suggesting that expediency and personal opinion played a role. A prominent concern was with herd immunity, with some choosing to believe that this was the government objective even at the cost of more deaths, which in turn put them off trust in the government altogether. One said, “I believe they continue to follow their herd immunity strategy as they consider the public loss of life acceptable.”

- Unclear and confused communication was another trust-eroding factor related to frequent policy changes and contradictory initiatives. Some attributed this to mixed medical opinions, others to the need for the government to present themselves in a good light, especially at press conferences, and hide their ignorance or lack of certainty. Some thought that this was acceptable as long as the communicators were open and honest, while some thought that trust-building exercises should be prioritized.

- Lack of transparent framing and implementation of policies especially dominated the discussion among those who thought the government had made some mistakes in intervention, such as delay in lockdown, for various reasons. Mistaken priorities, poor quality of evidence, and the need for political gain were some of the wrong factors behind such loss of transparency. Some of the key interventions targeted included the poor condition of the NHS relative to pandemic preparedness, poor planning, and lack of adequate personal protective equipment and testing.

Implications and Future Directions

The researchers say, “Our findings offer some initial insights on the complex role that transparency plays in citizens’ perspectives of the government’s response to COVID-19.” For instance, while over half approved of government decisions, not all thought the government was being truthful all the time or even mostly. This calls into question the perceived need for transparency in building trust in good government.

Secondly, the acceptance by some respondents of the need for vigorous enforcement of behavioral changes in an emergency might impact democratic values, but is mostly an “us vs them” picture, leading to possible discrimination against a subset of citizens.

Despite the limitations of the study, including its lack of generalizability, the study throws up some important conclusions. Still, the lack of respondents belonging to some of the communities that face the most significant racism and discrimination at personal, social, and institutional level makes it important to explore “the political consequences of epidemic control measures in contexts of structural inequality.”

Again, more research is required to understand how public trust in government changed across the course of the pandemic. It is necessary to improve this by “measures such as targeted community engagement that tailor messaging and public deliberation to the realities faced by particular social groups.”

Source

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources