As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread in many parts of the world, governments are desperately trying to balance the need to contain the spread of the virus against the social and economic cost of physical distancing measures and closures at schools and workplaces. A study recently published on the preprint server medRxiv* in September 2020 by researcher Richard Beesley at Juvenile Arthritis Research reports on the impact of school reopenings on the spread of the virus.

Early in the course of the pandemic, in many countries, schools and colleges closed down to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission. Since then, some governments have allowed reopenings to happen. The current study aims to examine the risk posed by school reopenings in terms of viral spread and the rise in the number of cases.

The researchers downloaded the number of new cases per day per country to calculate the seven-day rolling totals for each day. This evened out the numbers to compensate for unrelated factors such as extreme variability in the degree of capacity at which testing centers operate on different days of the week.

All countries in this survey had a seven-day total of 5,000 or more new cases on one day or more since the recorded start of the pandemic in their country. The sizeable daily case threshold excluded the possibility that trends would be inadvertently masked. All the included countries had one or more clear wave or peak, but not an ongoing first wave. Where different regions follow independent schooling systems and dates, unified national data is not available, as in the USA, and such countries were also excluded. Again, if the variability is considerable, data collection is likely to be of a poor standard, and this was an exclusion criterion as well.

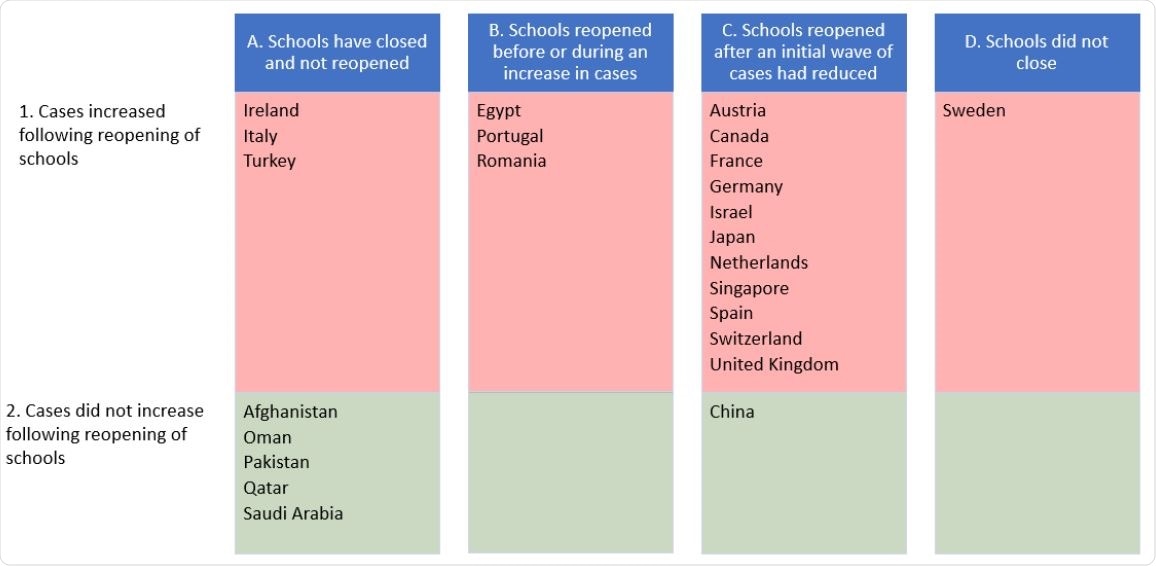

Categories of the national decisions about school reopening and the impact on the number of new confirmed cases of COVID-19 (based on 7-day rolling totals).

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Finding Patterns

The analysis mapped the reopening policy and the timing of school closure and reopening on to the case total, looking for either of two outcomes – an increase or absence of an increase in cases.

They found four patterns:

A. In the first, schools closed but had not reopened, and the total number of cases is not a factor of school openings. Countries showing this pattern belong to two categories, those with a rising pattern and those with a continued low number of cases.

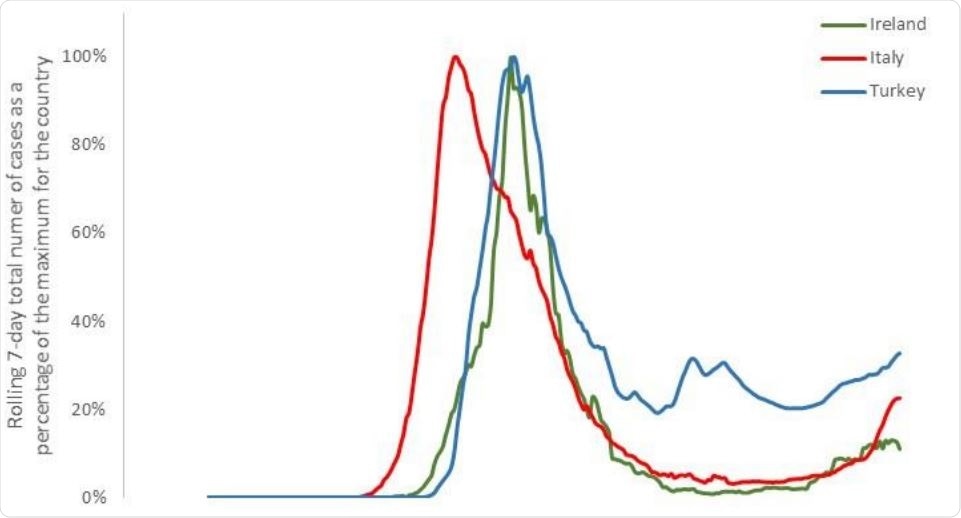

In Ireland, Italy, and Turkey, for instance, cases rose while schools remained closed, because of relaxed visiting and traveling norms, and a higher number of holidays. Another five countries showed a stable case total, perhaps because more restrictions are still in place.

The trend of cases in three countries that closed schools but have not yet reopened them, yet have seen an increase in cases. Line is shown as a percentage of the maximum for each country to give comparability, based on the 7-day rolling total number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases.

B. was where schools closed and reopened either before or while cases were going up. This applies to Egypt, Portugal, and Romania, and the result is to mask the impact of school reopening.

In the third or category C, reopening happened after a fall in the initial number of cases, and two subcategories were identified: one in which cases rose, and the other with a continued low number of cases. Most countries belonged to this category, showing a rise in cases after the initial peak that occurred at a mean of 37 days from the date of reopening. The second category contains only China, which has vigorously applied widespread testing, case tracing, isolation, and closure of schools where an outbreak was feared.

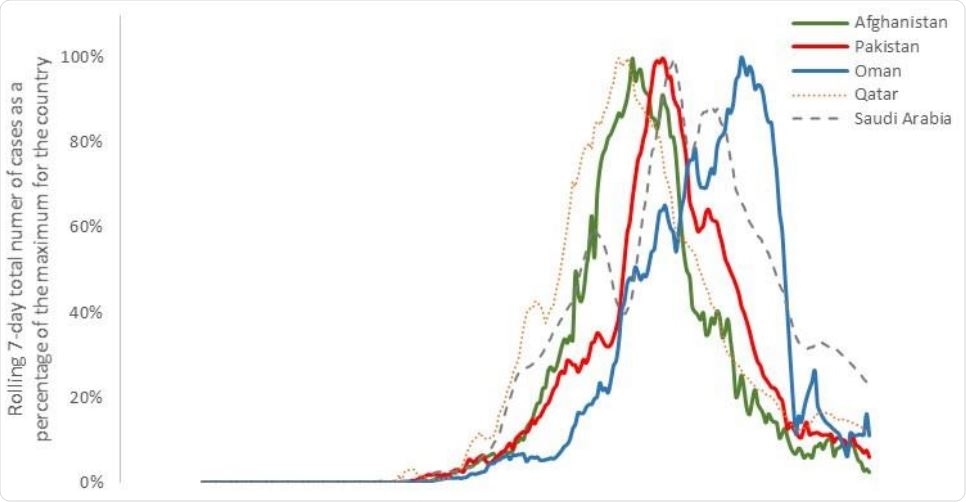

The trend of cases in five countries that closed schools but have not yet reopened them, and have not seen an increase in cases. Line is shown as a percentage of the maximum for each country to give comparability, based on the 7-day rolling total number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Why Cases Rise after Reopening

The cause of a reopening-related increase in cases is probably due to more than one cause since heterogeneous patterns of increase are seen. This includes the relaxation of travel and tourism restrictions, especially where this allows visitors from other countries with higher COVID-19 incidence. Other factors include parents returning to workplaces as schools reopen, children returning to the care of other family members other than their own parents, and greater use of shops and other leisure facilities.

However, school reopening is probably one of the contributing factors, since the rise in cases surpasses that expected from relaxed travel restrictions alone. Again, where school reopening was cautious and gradual, the delay before the rise in case numbers was more significant, as with Canada, Singapore, and the UK.

Where these limitations are still in place, case numbers continue to be low.

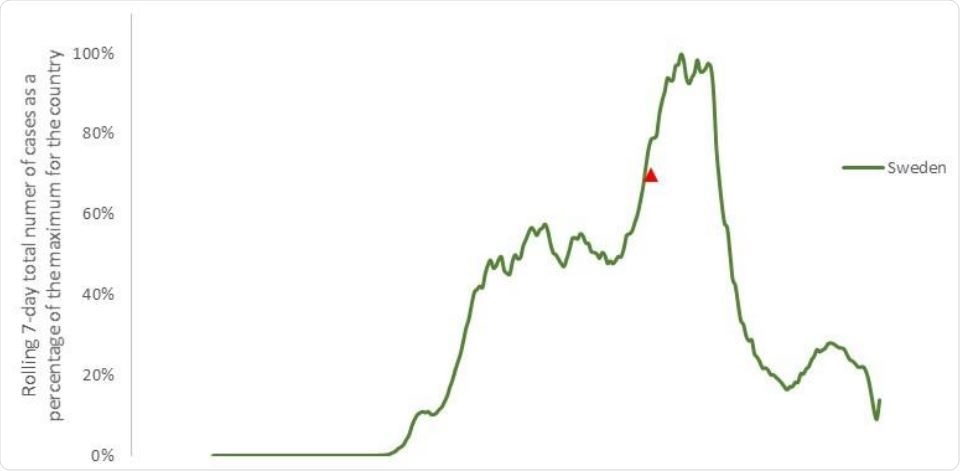

D. The last pattern was where schools remained open throughout. This was seen with Sweden, where, the researchers say, “politicians from that country have announced that keeping schools open did not lead to an increase in cases.” The study does point out that Swedish schools closed for the summer on the ninth of June, and 23 days later, the seven-day rolling total case numbers started to dip. This agrees with the findings in other countries where case increases followed school reopening with around the same timescale. This raises considerable doubt as to the scientific foundation of their former assertion.

Trends of new cases in Sweden, which closed schools for the summer holiday and saw a decrease in cases of COVID-19 as a result. Line shown as a percentage of the maximum for each country to give comparability, based on the 7-day rolling total number of new confirmed COVID-19 cases. Date of schools closing is indicated by a triangle.

Implications

The data indicate that the increase in cases in all countries where schools have reopened is higher than in places where they remain closed. Another confounding factor is the increase in viral spread due to summer holidays, which blurs the extent of the change due to school reopening. Nonetheless, the latter is an important contributor.

English schools opened two weeks later than those in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Within this short period, outbreaks had begun in 53 schools, involving 106 students and teachers, with 18,000 individuals in quarantine. This casts a grim shadow over reopening attempts in the UK, which has limited ventilation and student spacing in classrooms. This is heightened where masks are not mandatory or are even not allowed.

The wrong focus on fomite transmission and symptomatic patients ignores the importance of aerosol transmission and asymptomatic spread. Such futile attempts at containment make it inevitable that viral spread will occur even more widely following school reopening in countries that refuse to focus on controlling viral spread by restrictions on travel and meetings in person, as well as tracking contacts and testing promptly, and isolating when the transmission is thought to have occurred.

The study concludes, “While reopening of schools following an initial peak and decrease in COVID-19 infections is desirable for a range of reasons, doing so without adequate controls and protections may lead to an exacerbation of spread within the school environment, which could then lead to increased community spread of disease.’

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.