Circadian rhythm can be described as the 24-hour internal clock in the human brain that balances cycles of alertness and sleepiness as a response to light changes in the environment. In addition to its pivotal role in regulating biological functions, the circadian rhythm has been proposed as a regulator of viral infections.

More specifically, the time of day when the infection occurred was found to be quite important for the disease progression of several different viral diseases/agents, such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and parainfluenza type 3 viruses.

It is noteworthy that all of these are respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of the ongoing and disruptive coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Importantly, we are still searching for an optimal tool for improving the prognosis of infection.

.jpg)

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a cell heavily infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (yellow), isolated from a patient sample. The black area in the image is extracellular space between the cells. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Genetic background of the circadian rhythm

It is known that the aforementioned rhythmicity highly relies on central and peripheral oscillators, whose activity depends on two main feedback loops governed by clock gene cascade under the regulation of the primary clock gene – Bmal1.

Consequently, the knock-out of Bmal1 strikingly decreases the replication of several different viruses – including Dengue or Zika. Moreover, among key proteins that are involved in SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the host, previous studies have shown that approximately 30% of them are associated with the circadian pathway.

However, the evidence of whether the circadian rhythm is implicated in SARS-CoV-2 infection of human cells is still lacking. This is why a research group from France, led by Aïssatou Bailo Diallo, MSc from Aix Marseille Université and IHU-Méditerranée Infection in Marseille (France), decided to tackle this research question head-on by using human monocytes.

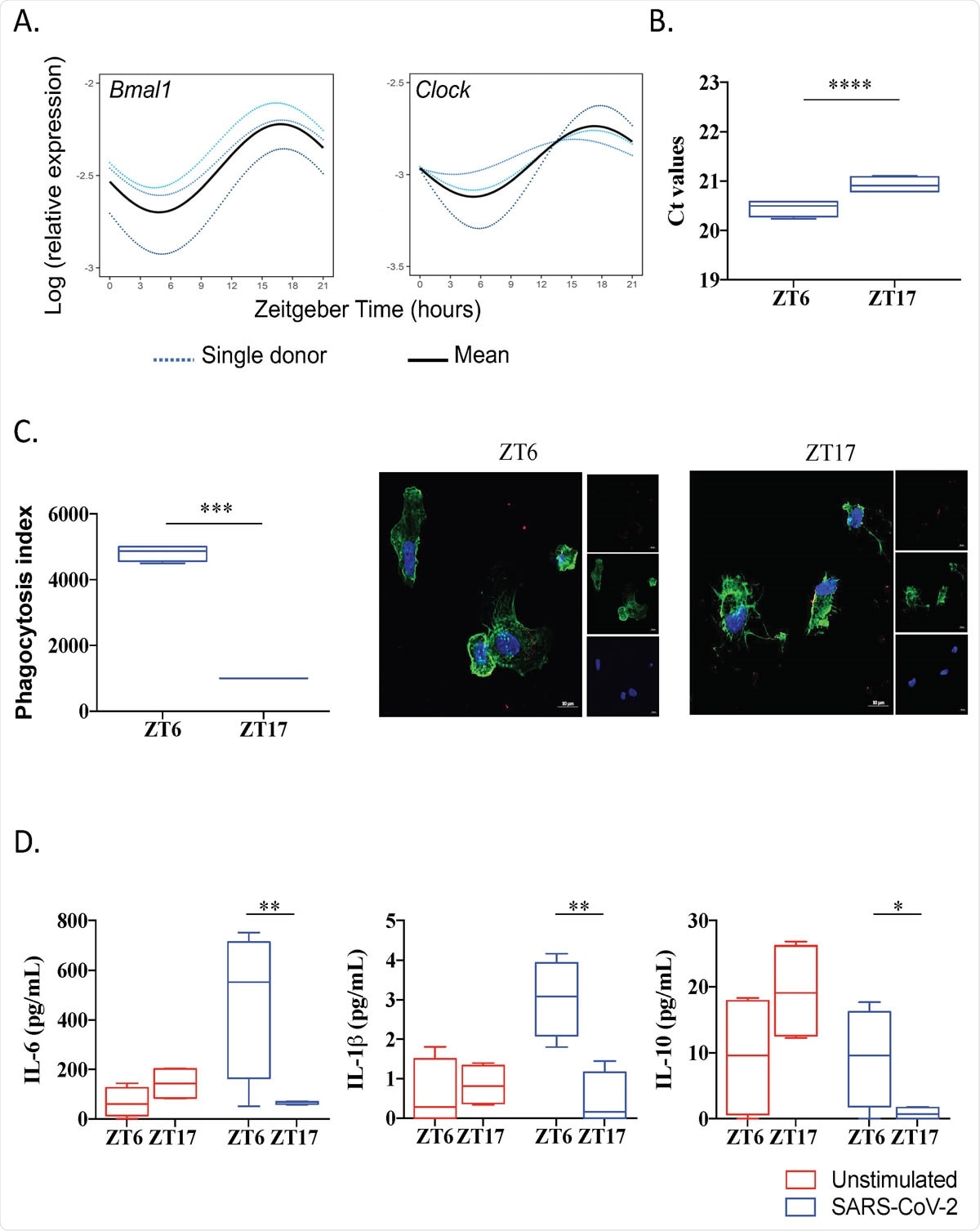

SARS-CoV-2 infection is link to circadian rhythm (A) Circadian rhythm of BMAL1 and CLOCK genes in monocyte using Cosinor model. (B) Virus load at ZT6 and ZT17 time. (C) Phagocytosis index and representative pictures of monocytes (F259 actin in green and nucleus in blue) infected by SARS-CoV-2 virus (red). (D) Level of IL-6, IL-1 and IL-10 of unstimulated (red) and infected cells at ZT6 and ZT17.

Investigating circadian oscillations

The researchers first wondered whether the infection of monocytes, which are innate immune human cells affected by COVID-19, adhere to circadian oscillations. During a 24-hour period, every three hours, total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted, and the expression of Bmal1 and Clock genes has been investigated in unstimulated monocytes.

The detection of SARS-CoV-2 was performed with the use of One-Step Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 was initially labeled with an anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody, followed by a secondary anti-rabbit Alexa 647 antibody.

All pictures were obtained with the use of confocal microscopy. Finally, all interleukin levels were measured in cell supernatants by employing an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method.

How SARS-CoV-2 exploits the clock pathway

"We demonstrate here that the time day of SARS-CoV-2 infection determines consistently viral infection/replication and host immune response", say study authors. "It is likely that SARS-CoV-2 exploits clock pathway for its own gain", they add.

The expression of investigating genes exhibited circadian rhythm in monocytes with an acrophase (peak of the rhythm) and a bathyphase (the trough of the rhythm) at Zeitgeber Time (German name for synchronizer) 6 and 17 (i.e., ZT6 and ZT17). Basically, these two-time points denote the beginning of the active and the resting periods in human individuals.

Furthermore, after 48 hours, the amount of SARS-CoV-2 increased in the monocyte infected at ZT6 in comparison to ZT17. Likewise, the amount of the virus at ZT6 was linked to substantially increased release of interleukin-6, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10 when compared to ZT17.

In a nutshell, the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with human monocytes prompted the rise of distinct cytokine patterns according to daytime, and for the first time, it was shown that cell entry and multiplication of SARS-CoV-2 in monocytes differs with the time of day.

Circadian rhythm and drugs

"Our findings support consideration of circadian rhythm in SARS-CoV-2 disease progression and suggest that circadian rhythm represents a novel target for managing viral progression", summarize study authors in their bioRxiv paper.

Furthermore, this study also emphasizes the significance of timing of any treatment solutions administered to COVID-19 patients, since circadian rhythm was found to be implicated in the pharmacokinetics of several different drugs.

Finally, the well-known circadian rhythm disturbance characteristic for intensive care units should never be neglected in the clinical management of patients presenting with severe forms of COVID-19.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources