As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to challenge existing health networks, a new study published on the preprint server medRxiv* in October 2020 reports on a strategy to address existing health care disparities in rural and urban areas of the USA. This should draw attention to the need for more such systems to ensure proper rural healthcare in the current and future pandemics.

Rural areas in the US have a higher prevalence of elderly patients with COVID-19 as well as those with chronic disease. With the long-standing lack of many medical specialties in such areas, deficits in hospital inpatient and ICU capacity and the increasing inability of rural hospitals to cope with COVID ensure that many rural USA patients will not receive adequate healthcare.

Another significant issue facing rural healthcare facilities is their lack of infrastructure and clinical experience, which denies them the opportunity to participate in clinical trials. As a result, the physicians in these areas either do not treat patients with COVID-19 or use medications off-label despite society's recommendations to reserve them for clinical trials.

How healthcare for this infection may be better delivered in one such area is the current study's focus. This is served by the St. Lawrence Health System (SLHS), a model with treats inpatients with a small team of specialists competent to deal broadly with many areas in their respective disciplines. It also serves as one of the spokes serving its hub hospital, Canton Potsdam Hospital (CPH).

Characteristics of Patients

This study notes the 20 inpatients' characteristics in the CPH over the first two months following the outbreak. Patients had a median age of 63, about 60% being female. Half were obese, while a fifth each had cardiovascular disease, lung disease/asthma, or obstructive sleep apnea. A tenth had diabetes mellitus.

Almost a third were smokers or had a history of smoking. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 3.2. Patients had been symptomatic for ~6 days, on average, prior to admission. 70% gave a history of contact with a known case before admission. The most common symptoms were cough, shortness of breath, and fever, all reported in half or more of patients.

Admission temperatures were elevated in a third, while a sixth had tachycardia. About 60% had fast breathing, and almost half had oxygen saturation below 93%. At the time of admission, over a third were on oxygen, while saturation was being measured.

Radiologic and Laboratory Findings

The researchers found that 93% of patients had positive radiological evidence of COVID-19 pneumonia on chest X-ray or CT. Markers of inflammation (LDH and ferritin) were high, with a low lymphocyte count. The latter declined still more over their hospital stay, while ferritin levels rose.

A sixth of patients had high troponin at or after admission.

Varying Clinical Course and Treatments

The researchers found that the median hospital stay duration was six days, with a fifth being admitted to the ICU. Of the latter four patients, two were shifted out after one day, while the others remained hospitalized for 19 and 27 days, respectively.

About half and over a third of patients met NIH criteria for severe and critical COVID-19. Among the seven patients in the latter category, all had respiratory failure, a little below half of the patients developed septic shock, and over 70% had multi-organ dysfunction. Over 85% had renal impairment, and many had liver inflammation.

Cardiac manifestations were observed in a sixth of patients, while 40% required supplemental oxygen, and a quarter was on ventilation. Various drugs were used as therapy, including hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, systemic corticosteroids, tocilizumab, and convalescent plasma, besides inhaled bronchodilators and vasopressors. The standard of care underwent numerous changes in accordance with ongoing research worldwide, accounting for the temporal shift in the type of medication used, the dosage, and the use of combinations.

Regarding the use of tocilizumab, a costly drug and one for which third-party insurance is frequently unavailable, the researchers worked out arrangements to include this in a clinical trial initiated at the end of the current study period. This shows how rural hospitals can be incorporated into ongoing research in order to broaden their access to expensive resources and to allow clinical decisions to be made based on the need rather than cost alone.

Only one patient died as a result of the previously made decision not to use invasive ventilation, while all others survived, with the mean WHO ordinal score of 4.3 on admission and the lowest score over hospitalization being 3.8, on average.

Hub and Spoke model for rural care delivery

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Implications and Recommendations

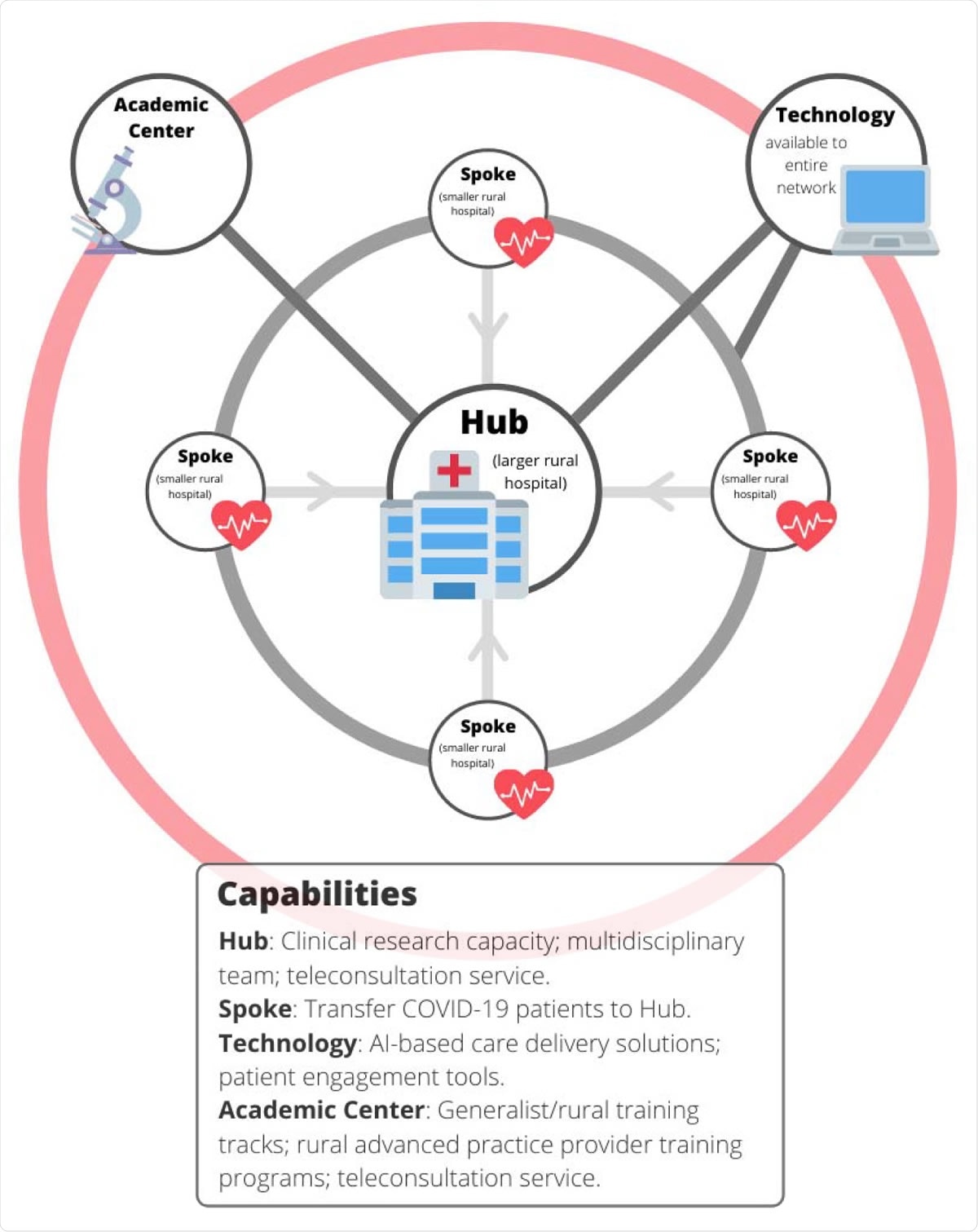

This is the first template study for the care of rural patients hospitalized with COVID-19. It illustrates the relevance of a spoke-and-hub design and the high efficiency that may be brought into play by rapidly setting up a small team of medical specialists who are generalists within their areas of expertise.

Such teams can cover inpatient care over a broad range of needs, including infectious disease, rheumatology, and pharmacy. The multidisciplinary approach to care allows the optimal use of limited resources to offer current care for COVID-19.

It also allowed the efficient and effective treatment of COVID-19 with multiple complications, achieving a low mortality rate without outside transfer, even without the use of remdesivir, dialysis services, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in this health system.

The researchers point out the significant difficulties they faced in gaining access to medications and convalescent plasma, with delays of up to 2 weeks in the latter's procurement from the date of request. This should stimulate efforts to upgrade infrastructure and clinical experience to the level that is essential for a clinical trial, thus improving access to novel drugs and treatments.

Again, the investigators say that adequate healthcare networks are always fundamental to crisis management, whether connecting staff at hub hospitals to those at the spoke, setting up better facilities and training opportunities, or streamlining available resources with centralized management. Moreover, rural practitioners should be in touch with academic professionals in their field in order to bring about improvement in both practice and research settings.

The authors suggest, “An improved version of this model would include a backup COVID-19 consultation team at a regional academic center, the incorporation of patient engagement and machine learning tools into care delivery, and research alliances that connect hub and spoke hospitals with larger academic partners.”

This will help rural areas cope with their own share of future crises, and the current model may guide the development of such systems.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Kedar, E. et al. (2020). COVID-19 In a Rural Health System in New York - Case Series and an Approach to Management. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.15.20213348. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.15.20213348v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Kedar, Eyal, Regina Scott, Daniel M. Soule, Carly Lovelett, Kyle Tower, Kylie Broughal, Daniel Jaremczuk, Sara Mohaddes, Imre Rainey-Spence, and Timothy Atkinson. 2021. “COVID-19 in a Rural Health System in New York – Case Series and an Approach to Management.” Www.rrh.org.au. July 13, 2021. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/6464. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/6464.