Findings from a new genomic sequencing study support the hypothesis that the pangolin was the intermediate host for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that enabled transmission of the virus to humans.

SARS-CoV-2 is the agent responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID—19) pandemic that poses an ongoing threat to global public health and the economy.

The study conducted by researchers in Australia and the United States demonstrated the similarity between sequences from SARS-CoV-2, the bat coronavirus RaTG13, and a Guangdong pangolin coronavirus (EPI_ISL_410721).

However, the study also revealed that not only the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 but also its 5' untranslated region (5’UTR) originated in the Guangdong pangolin coronavirus.

ACE2 is the human receptor the virus uses to bind to and fuse with host cells, while the viral 5’UTR is needed to regulate transcription.

“Altogether, our analyses indicate that both the 5’UTR and ACE2-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 genome have a pangolin coronavirus origin,” say Diako Ebrahimi (Texas Biomedical Research Institute) and colleagues from the University of Texas Health Science Center and the University of New South Wales.

“Therefore, our data support the hypothesis that the pangolin was the intermediate species for SARS-CoV-2 transmission into humans,” they add.

The study also found no evidence to support the theory that the zinc-finger antiviral protein (ZAP) played a role in the emergence of the virus by targeting its CpG motifs.

A pre-print version of the paper is available in the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

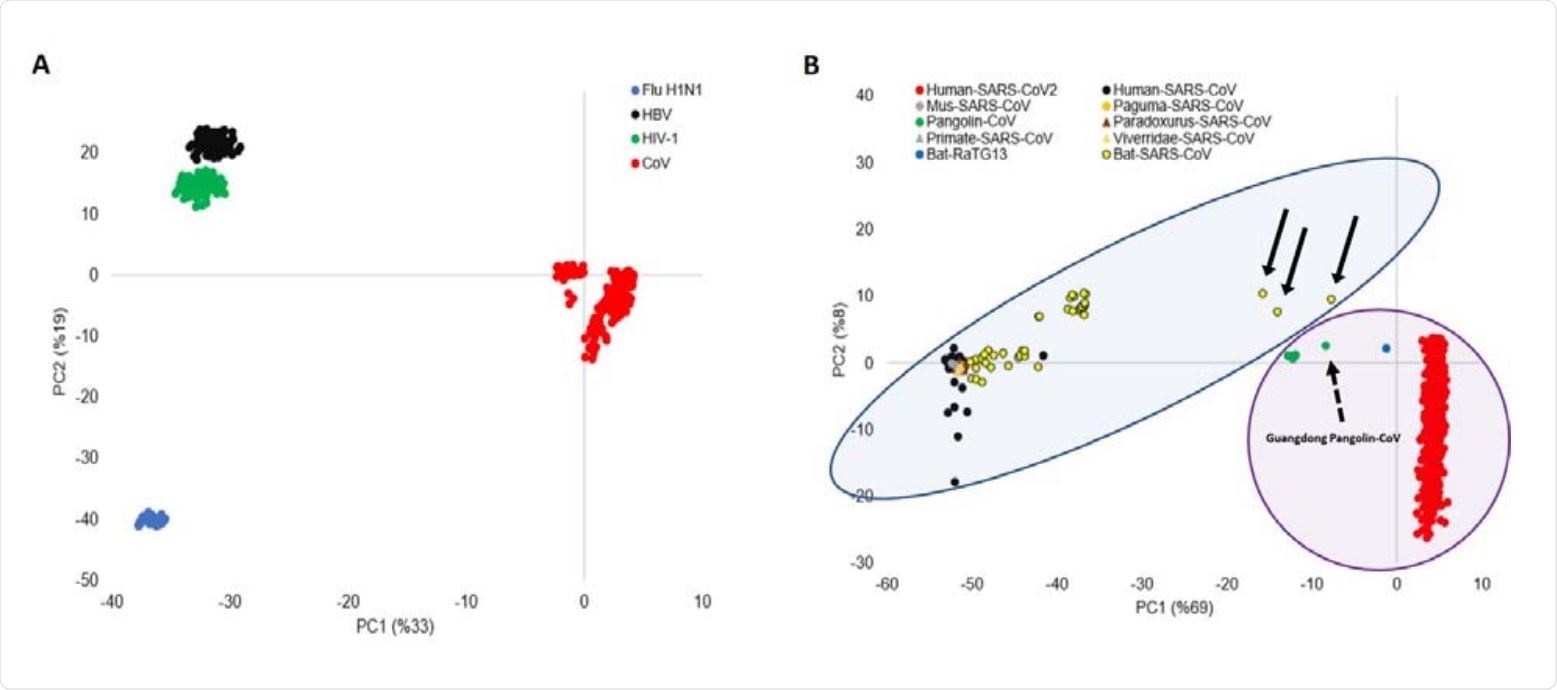

PCA of viral motifs representations. D-values of all dinucleotide and trinucleotide motifs in all viral sequences form a matrix, which is used as an input for PCA. (A) PC1-PC2 plot shows four clusters, one for each virus family: H1N1, SARS-CoV, HBV, and HIV-1. (B) PC1-PC2 plot classifies SARS-CoV viruses into two clusters. SARS-COV-2, Bat-RaTG13, and Pangolin-CoV formed a cluster (SARS-CoV-2-like group), which is separated from the rest of coronavirus sequences Human-SARS-CoV, Paguma-SARS-CoV, Viverridae-SARS-CoV, Paradoxurus-SARS-CoV, Bat-SARS-CoV, Mus-SARS-CoV and Primate-SARS-CoV (SARS-CoV group). SARS-CoV-2-like and SARS-CoV groups are highlighted with purple and blue circles. The three Bat-SARS-CoV sequences are located close to the SARS-CoV-2-like group, which is shown by black arrows. Guangdong Pangolin-CoV is shown by a broken arrow.

Unique features of the SARS-CoV-2 genome

The SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome has unique features that may play a role in its high pathogenicity and cross-species transmission.

So far, comparative genomic studies have shown that, overall, SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to RaTG13, a coronavirus isolated from the intermediate horseshoe bat. However, the genomic sequence coding for the virus's ACE2 binding site also closely resembles the sequence found in a Guangdong pangolin coronavirus.

As well as this unique feature, SARS-CoV-2 also has a low abundance of CpG. The suppression of CpG in viruses is well known, and studies have reported that the CpG composition of positive-strand RNA viral genomes often mimics the CpG content of their hosts.

“This suggests host CpG manipulating mechanisms play a role in shaping +ssRNA viral genomes during cross-species transmission,” write the researchers. “Nevertheless, these molecular mechanisms are not fully understood.”

One suggested mechanism is that these CpG sites are recognized by the host RNA-binding protein ZAP, which is known to bind to CpG-rich regions and induce a viral RNA degradation process.

However, although ZAP has a broad antiviral role, it does not suppress all viruses, says the team.

What did the current study involve?

Ebrahimi and colleagues used a comparative genomics approach to investigate the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

To explore any role that ZAP may play in lowering the CpG content of SARS-CoV-2, the team also analyzed the representations of short sequence motifs in viral genomes, the expression of ZAP, and the preference of ZAP for CpG motifs.

The analyses revealed a high level of similarity between SARS-CoV-2 sequences and those of the bat coronavirus RaTG13 and the Guangdong pangolin coronavirus (EPI_ISL_410721).

However, a high similarity was also observed between the 5’UTR of SARS-CoV-2 and the 5’UTR of the pangolin coronavirus.

This shows that not only the ACE2 binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 but also the 5'UTR of SARS-CoV-2 likely has a pangolin coronavirus origin, says the team.

“This suggests that bat and pangolin coronaviruses have likely recombined at least twice (in the 5’UTR and ACE2 binding domains) to seed the formation of SARS-CoV-2,” write the researchers.

Therefore, the data support the hypothesis that the pangolin was the intermediate species for SARS-CoV-2 transmission into humans, they say.

The team also says it remains to be determined whether the high pathogenicity and transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 is due, at least in part, to its unique 5’UTR sequence.

What about the role of ZAP?

The study found no evidence to suggest that the low CpG abundance in SARS-CoV-2 is related to an evolutionary pressure from ZAP.

Changes that were observed in motif representation were not exclusive to CpG. The CpG motifs preferentially targeted by ZAP did not have a lower representation than those that were not often recognized by ZAP.

“This, however, does not imply ZAP plays no role in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2. In fact, it has recently been shown that ZAP can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro,” write the researchers.

“To better understand the role of ZAP and other restriction factors in the inhibition and/or evolution of viruses, a global analysis of viral genomic composition is needed,” they conclude.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Ebrahimi D, et al. Evidence for ZAP-independent CpG reduction in SARS-CoV-2 genome, and pangolin coronavirus origin of 5′UTR. bioRxiv, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.23.351353 , https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.23.351353v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Afrasiabi, Ali, Hamid Alinejad-Rokny, Azad Khosh, Mostafa Rahnama, Nigel Lovell, Zhenming Xu, and Diako Ebrahimi. 2022. “The Low Abundance of CpG in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome Is Not an Evolutionarily Signature of ZAP.” Scientific Reports 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06046-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-06046-5.