Caused by the highly contagious pathogen, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the feared but expected the second wave of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has already hit the UK. This can be seen in the current high prevalence of infection across the country. Thus, the virus is poised to take a high toll on the country’s public health - and ultimately many of its citizen’s lives - unless prompt containment measures are put in place, says a recent study published on the preprint server medRxiv.*

The first wave of the pandemic in the UK occurred from March and April 2020, characterized by a high infection peak and then a steep and continuing decline in new infections that lasted until the beginning of August. From this point on, there has been a steady rise in infections, with the reproduction number (R) staying above 1, indicating a propagating epidemic.

Increasing Prevalence

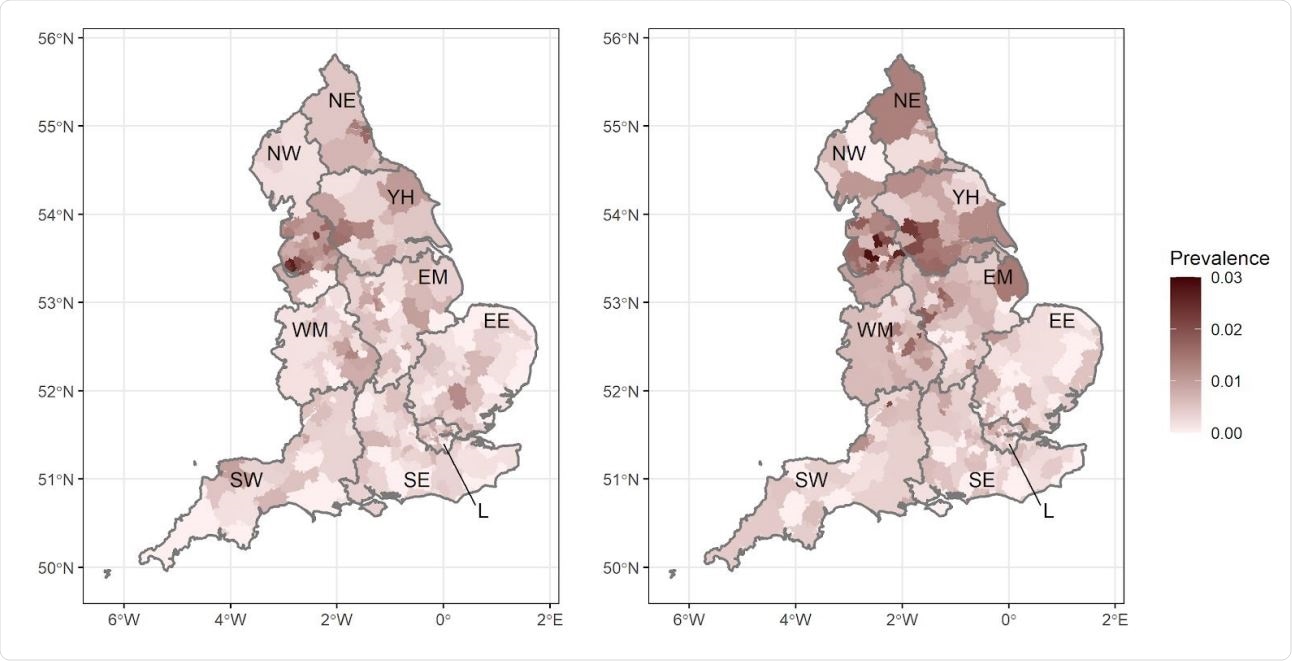

The current paper reports the preliminary findings of the sixth round of the REal-time Assessment of Community Transmission-1 (REACT-1) study, which has traced the path of the outbreak in England since May this year (2020). The fifth-round results, based on the examination of viral RNA testing by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) from September 18 to October 5, showed the national prevalence to be at high levels again; 0.60%, with a high concentration of cases in the northern parts of the UK.

The sixth round of testing occurred between October 16 and October 25. This included around 86,000 swabs, of which approximately 860 were positive, for a crude prevalence of 1%. However, the weighted prevalence is 1.28%, which indicates the prevalence has more than doubled within 20 days.

Prevalence of swb-positivity by lower-tier local authority for England for round 5 (left) and round 6 (right). Regions: NE = North East, NW = North West, YH = Yorkshire and The Humber, EM = East Midlands, WM = West Midlands, EE = East of England, L = London, SE = South East, SW = South West.

Increasing Reproduction Number

This increase in prevalence also yielded a reproduction number of 1.20 for round 5 and 6. While this is similar to the 1.16 reported in round 5, isolated round 6 results indicate that the reproduction rate has increased very recently. In fact, the doubling time for the UK in round 6 is now 9 days, which suggests an R-value of 1.56.

These results indicate a higher prevalence and R-value, whether the number of double gene positives in both rounds is used, or if the Ct value for the N-gene is used, as well as for asymptomatic individuals. Overall, however, the prevalence has increased in all regions since the last round.

The weighted prevalence is highest, at 2.72%, in the north of England; namely, in Yorkshire and The Humber, while in the Northwest, it stands at 2.27%. Here, however, the highest rate of growth appears to have shifted from 18 to 24-year-olds to older people and schoolchildren.

The lowest weighted prevalence is in the Southeast of England, at 0.55%. However, these figures can mislead since the growth of the outbreak is now highest, with the R-value being above 2 in the Southeast and East of England, London and the Southwest. The highest rate of growth in the Southwest is still among those aged 18-24 years.

Rapid Viral Spread

The researchers say that it is 99% probable that the R-value is above 1, indicating a propagating epidemic in most of the regions in the second group, while in the South West and West Midlands, the probability is somewhat lower, possibly between 95% and 99%.

High-Risk Groups Being Infected

While all age groups had a higher prevalence in this round, the biggest rise came in 55 to 64 age group, at 1.20%, which denotes a threefold increase from the previous round prevalence of 0.37%. The prevalence was doubled to 0.81% in the 65 and above group. However, the highest prevalence continued to be in the 18 to 24 age group at 2.25%, up from 1.59% in the last round.

Unemployed people are less likely to contract the infection, at 0.64%, compared to those who come into contact with others during the course of their work. Those living in wealthier areas also had lower odds of infection as judged by swab positivity. Thus, both age and socioeconomic deprivation appeared to be the factors that chiefly influenced the odds of swab positivity.

In the last two rounds, infection clusters seem to be predominantly in Lancashire, Manchester, Liverpool, and West Yorkshire.

The researchers say that these October 2020 findings represent an acceleration in the second wave of infections in England. This is shown by the increased R-value of 1.6, up from 1.2 earlier, while more infections are occurring in older high-risk individuals above 65 years, rather than only in the low-risk 18 to 24 age group.

Moreover, the prevalence, which was highest in northern England, is now showing signs of a downturn. This is despite the significant increases in prevalence still observable among individuals 65 years and over. In fact, the highest rate of growth is now seen in the Midlands and the South of England, which is mirroring the age group and growth patterns previously seen in North England during rounds 4 and 5.

Current Interventions Are Not Sufficient

The government has implemented several non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce the rate of viral spread during required social and economic interactions. These interventions include free testing (with mandatory isolation and quarantine of infected individuals and their households), contact tracing and quarantine, and the tracking of contacts (or possible exposures) in case of infection clusters. Social gatherings are also limited in size by law, and masks are required to be worn in shops and on public transport.

Some regions have more strict limitations on the type of economic activity allowed, with hotels, restaurants and bars bearing the brunt. Those working in these services are exposed to most external visitors who are themselves at the highest risk of having incurred infection.

The problem, the researchers point out, is that the policies themselves, singly or combined, along with the planned relaxation of restrictions by risk tier, and the current compliance rates, are not enough to bring down the R-value to below 1, which means the epidemic will continue to spread.

In fact, they estimate that on average, there are around 1 million infected individuals in England on any one day at present prevalence, assuming that nasal and oral swabs have a 75% sensitivity to the virus, and that viral detection is possible up to 10 days from infection.

Previous data rounds have shown that half or more of patients with positive viral tests have no symptoms at the time of testing or during the preceding week. This indicates that if only symptomatic cases are counted, the population incidence will be falsely low.

Implications

All individuals with symptoms may not have chosen to participate in the current survey, but this may not have affected the results significantly. Secondly, the researchers used self-taken swabs which may have yielded false negatives in 20% to 30% of participants. However, this should not affect the trends as this has been the practice in all the rounds up to the current one, and because the laboratory procedures used in all rounds have been identical.

The researchers, therefore, conclude, “The second wave of the epidemic in England has now reached a critical stage.” The inevitable outcome of accelerating transmission will be heavy hospitalizations and a high mortality rate. To avoid this, they urge, “Whether via regional or national measures, it is now time-critical to control the virus and turn R below one.”

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.