Scientific publications disseminate the results of laboratory investigations and fieldwork conducted by scientists. In the case of novel pathogens, this helps all involved in the study of the infectious agent to pool the information, informing interventions by governments, healthcare agencies, and other researchers. The current study deals with the two recent viruses that have caused the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Zika virus is an arbovirus that has been around since 1947 but came into the limelight in 2015 when it was discovered to be associated with microcephaly in children born to mothers infected with this virus during pregnancy.

SARS-CoV-2 was first known early in 2020 as the cause of COVID-19, a respiratory illness with a frequently fatal outcome.

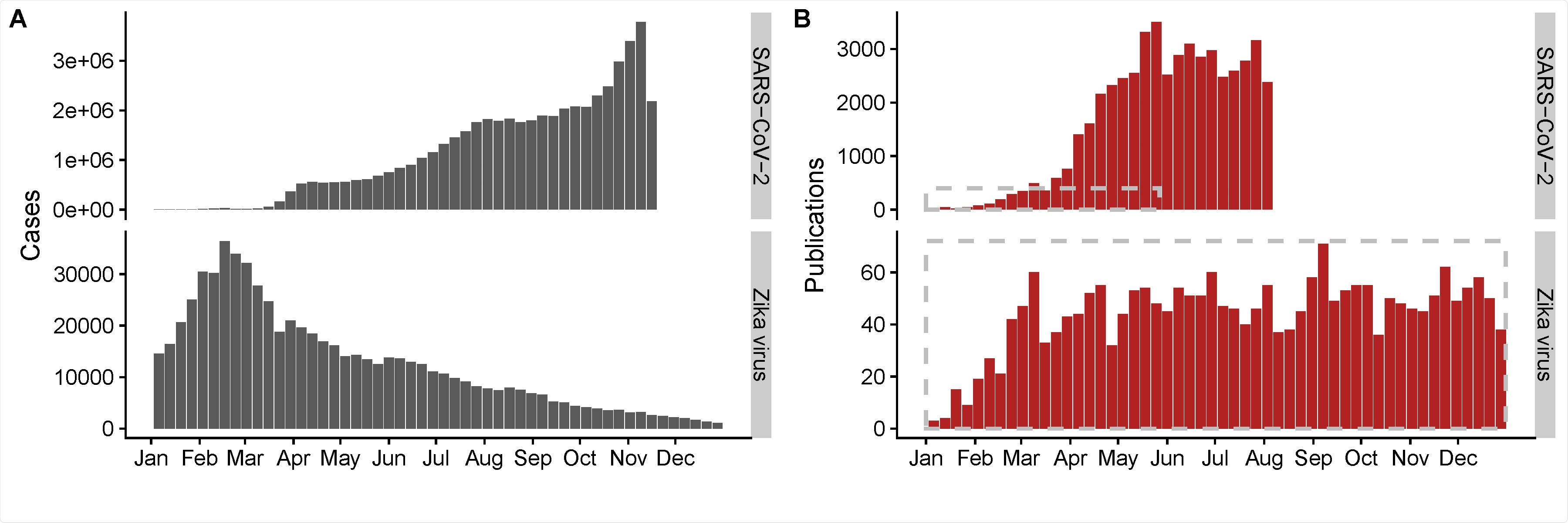

Both triggered “an outbreak of publications” aimed at producing answers to the problem of containing viral transmission, preventing the illness, and large-scale interventions. While the Zika virus led to hundreds of new papers, SARS-CoV-2 has been responsible for about 2,000 papers a week, from April 2020 onwards.

The global number of reported cases (A), and the number publications (B) by week for SARS-CoV-2 infections in 2020 and Zika virus infections (ZIKV) in 2016. In panel B, the dashed grey boxes contain the period and number of publications for which the study design was annotated. The vertical scales differ for each infection. SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The current study explores the emergence of scientific evidence and the quality of the methods used in all classes of studies, whether case reports, epidemiological studies, or randomized controlled studies. Each has its place, say the researchers, in dealing with different objectives.

The investigators postulated the following sequence of appearance of studies: firstly, case reports or series, describing individual observations, then systematic observational studies, accompanied by studies on the virus and the disease itself, which is called basic research. This is also associated with modeling studies that cover areas lacking direct observational evidence. After a lag, interventional controlled studies appear.

The researchers tested this with reference to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. They systematically searched for all publications dealing with these viruses. They then classified and compared the various study designs for both over this period.

They found that from week 1 to 21, up to May 2020, there were about 2,300 and 22,000 publications about Zika and SARS-CoV-2 virus, up to the end of May 2020. Thus, the latter had about 30-50 times fewer publications than SARS-CoV-2. The scientists randomly selected about 5,300 studies on the latter but used all the Zika papers.

In both epidemics, a substantial and reasonably stable proportion of the publications were non-original research. The overall proportion of non-original publications was higher for the Zika virus (55%, than for SARS-CoV-2 (34%). For publications of original research, the proportion of basic research publications increased over time for the Zika virus but decreased for SARS-CoV-2 research.

Mathematical modeling studies were more common near the beginning of the current pandemic, forming a tenth of all papers. This may have been because world health authorities recognized the virus's potential to cause a pandemic and required reliable forecasts of multiple aspects of the agent and disease.

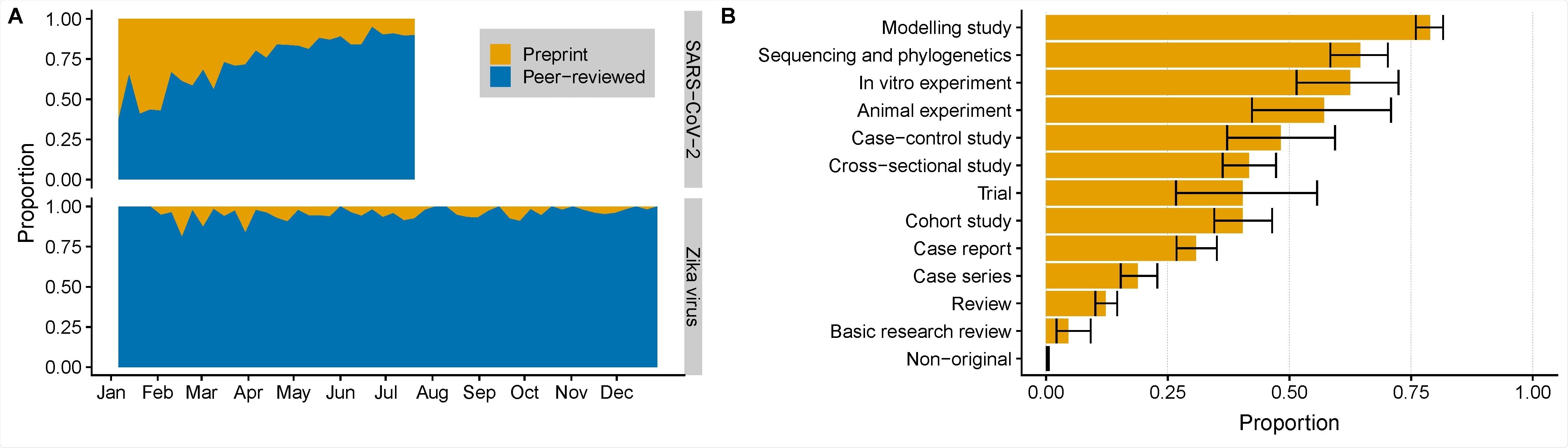

Many COVID-19 papers were preprints, and in fact, these made up the largest share in the first two months of the year. However, most basic research reviews appeared in the published form first. Conversely, over three-quarters of mathematical modeling studies were first preprinted, and these, along with phylogenetic studies, continued to form a high proportion up to May 2020. Overall, the percentage of preprints went down with time.

The proportion of preprint publications and peer-reviewed publications for SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Zika virus (Zika virus) research over time (A) and by study design for SARS-CoV-2 (B). SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Preprint volume may be correlated with the surge in open access journals as well as the urgency of the requirement that more be known about this virus.

If only published papers are included, both the research streams follow the same course. About a tenth of all papers consisted of case reports or series, and these were also the first to appear. Early on, there were also many laboratory studies, both in vitro and in vivo, especially in the current pandemic, along with mathematical modeling and studies on phylogeny.

Analytical epidemiological studies then began to be published, including cohort and case-control studies. These made up 4% and less than 1% for SARS-CoV-2 and Zika, respectively, probably because the former caused 50 times as many cases as well as spreading all over the world. These took longer to appear with the Zika virus.

Randomized trials were the latest to emerge, forming a small percentage, at 1 of 2,300 Zika studies and 27 of 5,300 studies on SARS-CoV-19.

Why is this important?

The researchers explain that the difference between the two illnesses determined the differences in the study designs. Zika virus commanded more basic research firstly because of the nature of the disease – congenital anomalies following an arthropod-borne virus infection. This was being seen for the first time, and the mode of transmission during pregnancy, as well as how it produced fetal damage, was unknown, promoting intensive research on the virus and its biology and disease mechanisms.

A second reason is that mouse models were far easier to produce for Zika than for SARS-CoV-2. Again, analytical observational studies may have come later in Zika because of the inevitable delay from infection to the appearance of the outcome, microcephaly.

Other researchers have pointed out that most papers dealing with the pandemic covered the clinical aspects, leaving many other vital areas incompletely covered. These include mental health, newer technological advances, including artificial intelligence, and the mechanism by which the infection causes severe and critical disease or death.

The authors indicate the need to use different sources of information, including living systematic reviews where the criteria can be modified as required to match advancements, in order to gain specific information about etiological factors and disease characteristics. Further, they point to the need to use sophisticated technology such as machine learning for the sorting of publications and crowd-sourcing among subject experts to enhance efficiency and the optimal use of all research findings.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources