An international team of researchers has conducted a study demonstrating the effects that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) control measures have had on people’s walking patterns in the United States.

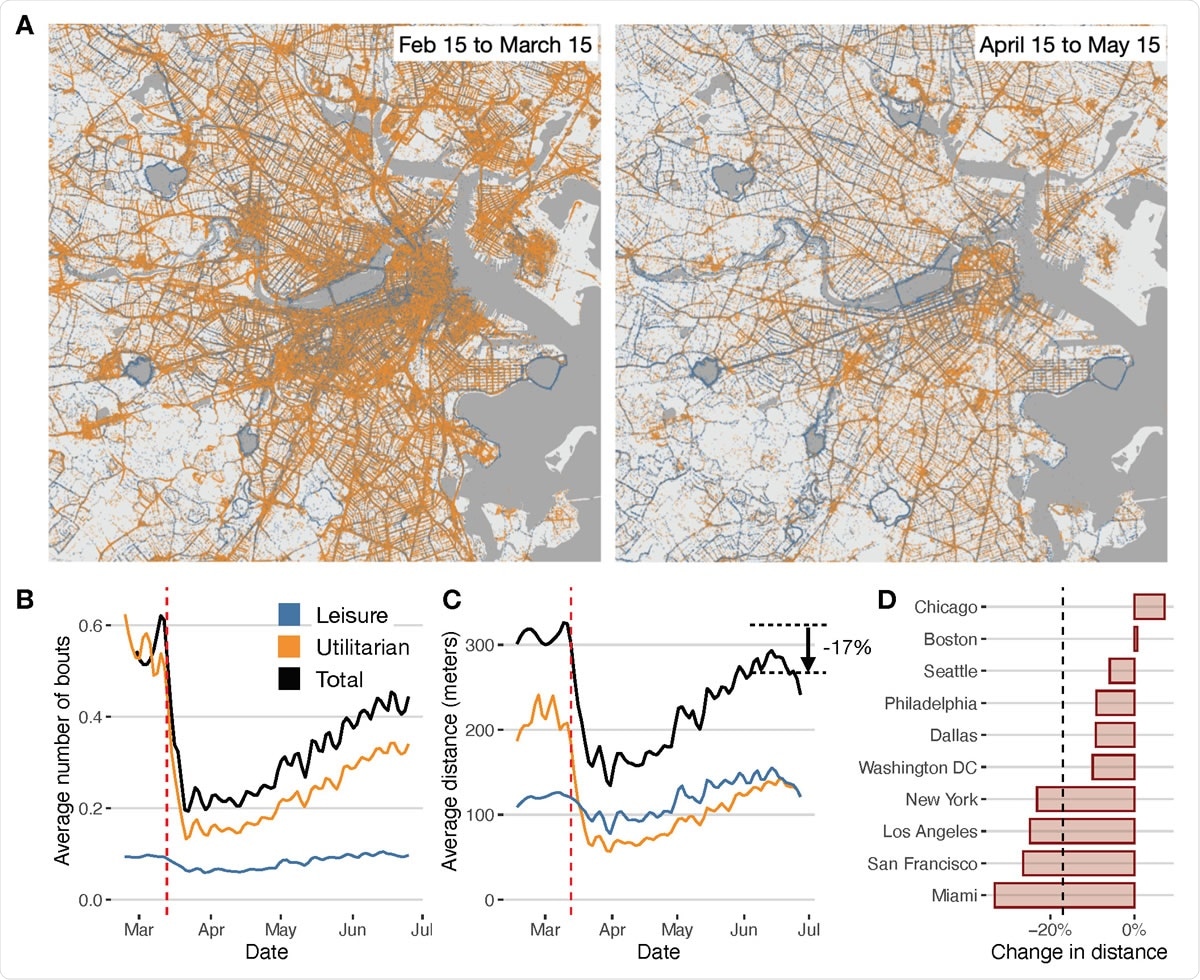

The team found that the average number and distance of walks dramatically declined following the declaration of a national emergency on March 13th, 2020, and the introduction of mitigation measures to control the pandemic.

Once restrictions started to ease after mid-May 2020, the average distance walked for practical purposes such as shopping (utilitarian walking) was still significantly shorter than before the pandemic. Recreational or leisure walking was less affected and recovered, sometimes even surpassing pre-pandemic levels.

However, Esteban Moro from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and colleagues say the study revealed differences in how walking patterns were affected across different sociodemographic groups.

The COVID-19 response measures had a more significant impact on the walking patterns of people living in low-income areas and areas where the use of public transportation is high.

“The experience of COVID-19 is not shared equally across our communities and neighborhoods, nor is its impact,” says the team. “Provision of equal opportunities to support walking could be key to opening up our society and the economy.”

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

Decrease in walking behavior during the pandemic. A) Geolocations of leisure and utilitarian walks in the Boston area before (left) and after (right) the introduction of COVID-19 response measures. B) Total (black) daily average number of bouts of walking by day and user in the 10 metropolitan areas, compared with those for utilitarian and leisure walks. Vertical (red) dashed line indicates March 13th 2020, the declaration of a national emergency. C) Same as in B) but for total distance walked. D) Relative change in distance walked by city between the pre-lockdown (Feb 15 2020 to March 15 2020) and post-lockdown (June 2020).

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

COVID-19 control measures have caused large-scale disruption to active living

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries introduced measures to restrict mobility and encourage citizens to stay at home as part of the effort to reduce transmission and prevent health services from becoming overwhelmed.

“Although key to containing the spread of the virus, such restrictions have caused large-scale disruption to our normal lives and active living,” says Moro and colleagues.

In the United States, walking is the most common form of physical activity and is consistently the most frequently reported physical activity among adults who meet public health physical activity recommendations.

“There is no doubt that mobility restrictions implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19 have impacted walking behavior, but the magnitude and spatio-temporal aspects of these changes have not been thoroughly demonstrated yet,” say the researchers.

Furthermore, little is known about the differential effects of COVID-19 control measures on population subgroups, which are likely to have distinct lockdown experiences depending on their degree of access to green spaces and urbanity, the team adds.

“Understanding how COVID-19 response measures have affected walking behaviors of populations and its distinct subgroups is important information to help devise strategies to prevent the potential health and societal impacts of declining walking levels,” write the researchers.

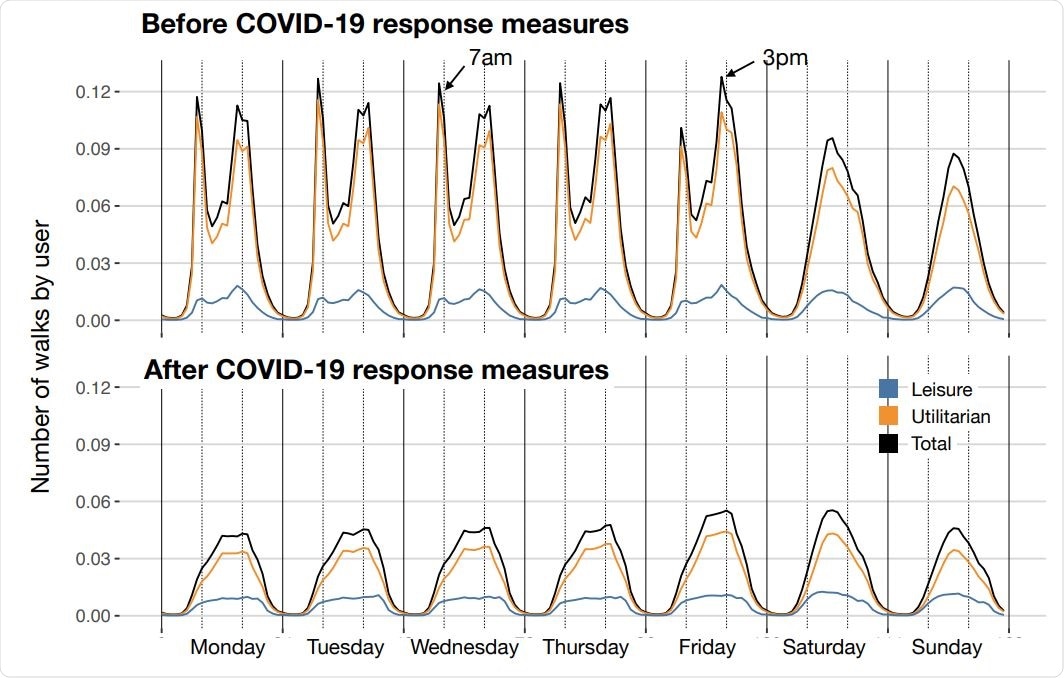

Temporal patterns of walking behavior. Panels show the average number of walks by user for each hour and day of the week, and those for leisure and utilitarian purposes. Upper panel corresponds to the temporal pattern before COVID-19 response measures and the lower panel after COVID-19 response measures.

What did the study involve?

The team integrated mobility data from mobile devices and area-level data to analyze the walking patterns of 1.62 million anonymous people across ten metropolitan areas in the United States between mid-February 2020 (pre-lockdown) and late June 2020, after lockdown restrictions had been eased.

“Mobile phones are a powerful tool with which to study large-scale population dynamics, revealing patterns of human movement at greater temporal and spatial granularity, while ensuring anonymity and user privacy,” say the researchers.

The areas covered included New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Miami, Dallas, San Francisco, Seattle, Philadelphia, and Washington DC.

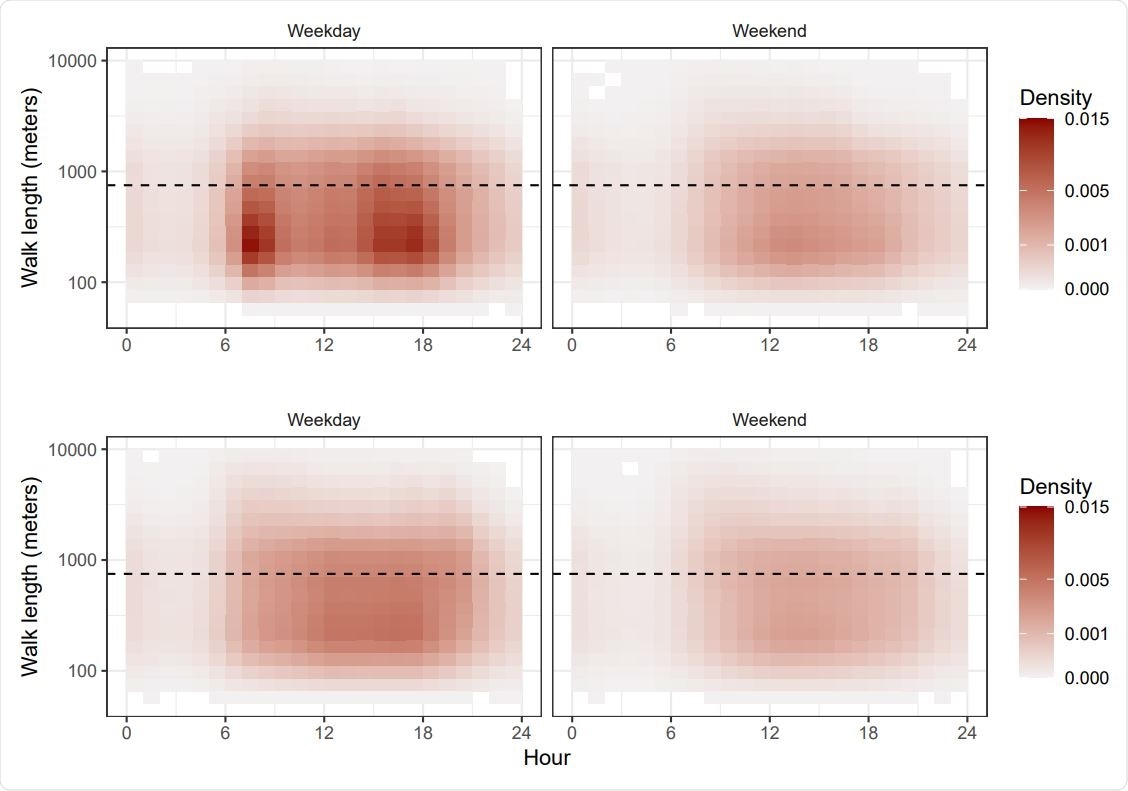

Panels A) to D) show the distribution of walks by hour of the day and length (in meters) for the walks before (upper panels) and after (lower panels) COVID-19 measures and for weekdays and weekends. Dashed line correspond to 750 meters.

Walking activity fell dramatically across all areas

Following the declaration of a national emergency on March 13th and the introduction of COVID-19 control measures, the average number of walks people took decreased by around 75%, and the average distance they covered fell by around 55% across all of the metropolitan areas studied.

The average distance traveled during utilitarian walking fell by around 72%, and there was a sharp reduction in the number of walks taken at around 7 am and 3 pm.

The results suggested that this impact on walking was primarily due to changes in working, shopping, and dining activities.

Even after restrictions were eased in mid-May, the average distance covered during utilitarian walking was still about 39% less than before the pandemic. The decrease in leisure walking was less pronounced and across some demographic groups, it recovered to levels that surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

Inequalities across sociodemographic groups were observed

People living in high-income areas increased their leisure walking by a significant 48%, an effect that may be due to high-income individuals having more free time and opportunities to engage in recreational walking, suggests Moro and colleagues.

“The substitution of utilitarian by leisure walking was not present in low-income groups and, as a result, the COVID-19 response measures have had a strong impact on their walking behavior,” they write.

The researchers also found that walking sharply decreased in areas where the use of public transport is usually high, compared to areas where use is usually low. This is likely due to a decrease in walking to access transport, says the team.

“In the US, public transport use is typically higher in low-income communities, which, according to our findings, suffered the largest decrease in walking behavior.”

Low-cost interventions could tackle inequalities

The researchers outlined a range of low-cost interventions that could potentially increase utilitarian and recreational walking behavior and tackle some of the inequalities observed during the study.

Examples include the creation of “pop-up” footpaths and the widening of pavements to provide more opportunities to walk. The team also suggests reducing speed limits in urban areas and adjusting the timing of traffic lights to favor pedestrians.

The researchers point out that if such interventions were implemented in the long term, they could help to improve population health and well-being by reducing air and noise pollution, reducing the risk of road accidents, and reducing the demand on health services, for example.

“We, therefore, have a unique opportunity to improve our urban environments to support and enable walking and physical activity, particularly for our most vulnerable communities,” they write.

“The novel methods applied in this work and our findings can help us to understand the prevalence, spread, and effects of walking within and across cities, countries and subgroups and to design communities, policies, and actions that promote greater walking in a COVID-19 secure world,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Moro E, et al. Effect of COVID-19 response policies on walking behavior in US cities. medRxiv, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.20245282, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.07.20245282v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Hunter, Ruth F., Leandro Garcia, Thiago Herick de Sa, Belen Zapata-Diomedi, Christopher Millett, James Woodcock, Alex ’Sandy’ Pentland, and Esteban Moro. 2021. “Effect of COVID-19 Response Policies on Walking Behavior in US Cities.” Nature Communications 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23937-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-23937-9.