The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is in its second wave in many countries due to the lifting of lockdown orders, re-opening businesses, and schools' opening.

A team of scientists wanted to know the impact of school contacts on the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. They also aimed to assess the effects of school-based measures, including school closure, on controlling the pandemic.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The coronavirus pandemic

COVID-19, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), first emerged in Wuhan City, China, in December 2019. Since then, it has reached over 191 countries and territories. It has infected more than 68.46 million people and claimed the lives of 1.56 million people.

During the pandemic's peak, many countries resorted to nationwide lockdowns to contain the spread of the virus. Included in lockdown measures were orders to close all businesses deemed non-essential and schools. Students began remote learning to continue with their studies without risking their health.

It is believed that children are less likely to be affected by COVID-19. If they become infected, they usually develop mild symptoms or none at all. However, when they contract it at school, they can still transmit the virus in their households.

The study

The study, published in the pre-print journal medRxiv*, highlights the risk of virus spread in schools in the Netherlands. Since most schools across countries have resumed in-person or face-to-face classes, knowing the virus's risk and transmission dynamics in this context is crucial.

To arrive at the study findings, the team obtained the estimates of epidemiological parameters by fitting a transmission model to age-stratified COVID-19 hospital admission data and cross-sectional age-stratified SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence data.

Compared to those older than 60, the team found that the estimated vulnerability was 23 percent for children and young people between 0 and 23 years old. For people between 20 and 60 years old, the susceptibility was 61 percent.

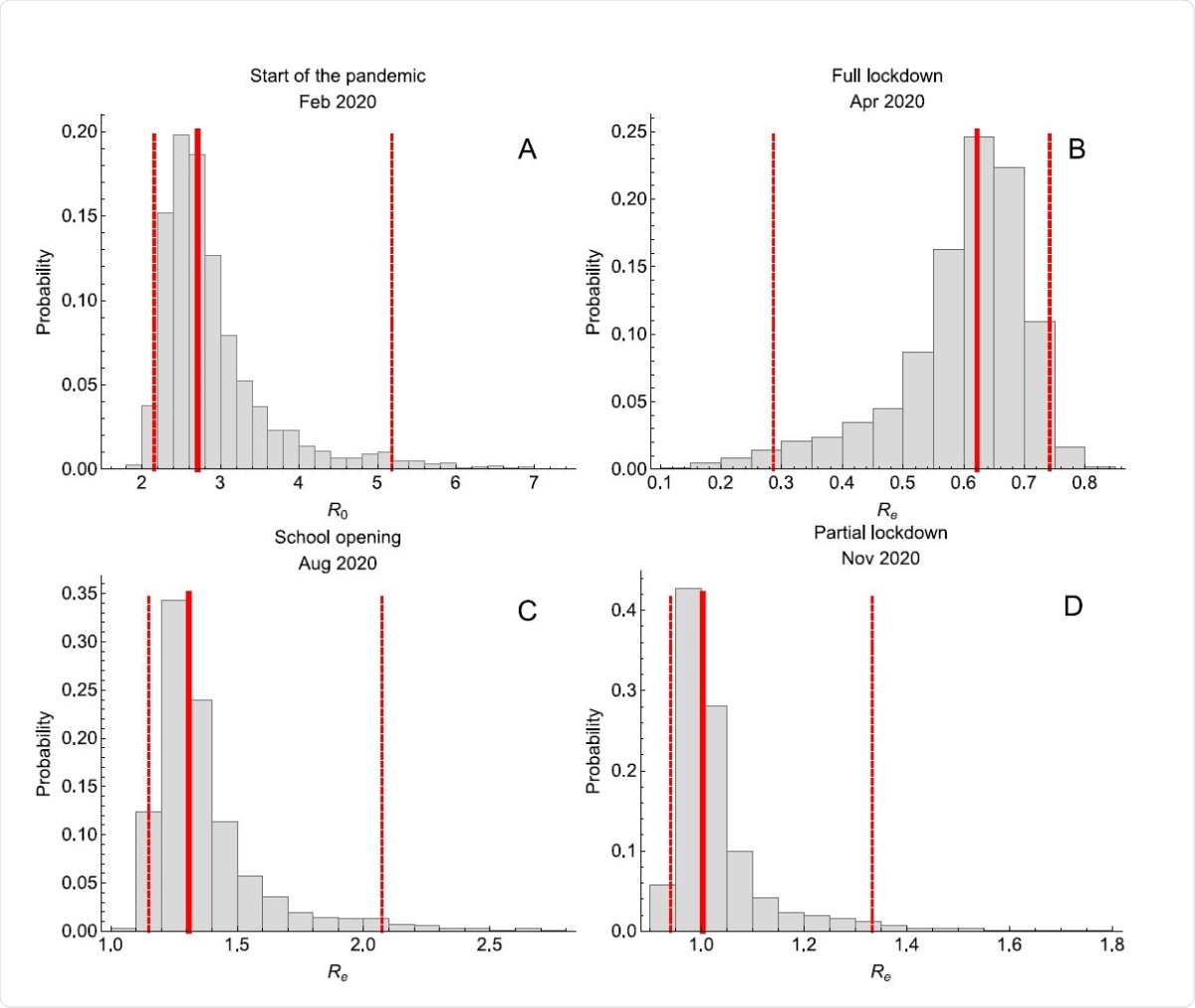

They also revealed that the time points considered in the analyses were first, August 2020, when the reproduction number was about 1.31, schools just opened after the summer holidays, and measures were implemented to reduce transmission.

The second time point was in November 2020, when measures had reduced the reproductive number to 1.00. In this period, the schools remained open in the Netherlands.

The study’s findings

The model predicts that keeping schools closed after the summer holidays would have reduced the reproduction number by 10 percent. This could have prevented the second wave of cases in autumn of 2020.

The team added that decreasing non-school-based contacts in August to the level observed during the first wave would have reduced the reproduction number to 0.83. However, this reduction was not attained in November.

The measures implemented since August had reduced the effective reproduction number to around 1, instead of achieving 0.84. The findings reveal that additional physical distancing measures in schools could further reduce the effective reproduction number, primarily when implemented in secondary schools.

Reproduction numbers. Estimated reproduction numbers (A) at the beginning of the pandemic (February 2020), (B) after the first full lockdown (April 2020), (C) at the time of school opening (August 2020), and (D) after the second partial lockdown (November 2020). Histograms are based on 2000 parameter samples from the posterior distribution. The solid and the dashed lines correspond to the median and 95% credible intervals.

The study findings suggest that physical distancing measures in the youngest children do not affect the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Better adherence to non-school based measures would still help reduce school-based contacts.

Schools can implement ways to reduce the number of contacts between children at school, such as staggered start, end times, breaks, different forms of physical distancing for students, and division of classes.

"The impact of measures reducing school-based contacts, including school closure, depends on the remaining opportunities to reduce non-school-based contacts," the team explained.

"If opportunities to reduce reproduction number with non-school-based measures are exhausted or undesired, and it is still close to 1, the additional benefit of school-based measures may be considerable, particularly among the older school children," they added.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Rozhnova, G., van Dorp, C., Bruijning-Verhagen, P. et al. (2020). Model-based evaluation of school- and non-school-related measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.20245506, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.07.20245506v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Rozhnova, Ganna, Christiaan H. van Dorp, Patricia Bruijning-Verhagen, Martin C. J. Bootsma, Janneke H. H. M. van de Wijgert, Marc J. M. Bonten, and Mirjam E. Kretzschmar. 2021. “Model-Based Evaluation of School- and Non-School-Related Measures to Control the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nature Communications 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21899-6. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21899-6.