Women in the healthcare workforce seem to be suffering stress and burnout in the current pandemic situation, disproportionately when compared to men, suggests a new preprint research paper published on the medRxiv* server.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed an immense burden on healthcare systems in many regions around the world. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are among the essential workers who come into close and prolonged contact with COVID-19 patients, exposing themselves to the potential risk of infection. In addition, they are faced with harassment, stigma, and both emotional and physical trauma as a result of their occupation, as other people fear that HCWs could ‘bring’ the infection to them.

All this has led to higher rates of stress, burnout, depression, anxiety, and coping mechanisms such as drinking and substance abuse. Suicide rates have also risen. In fact, Amnesty International has reported that over 7,000 HCWs have died since the pandemic began, while in the USA alone, almost 1,000 deaths have been reported among HCWs.

Women in healthcare under greater stress

Women are faced with more significant burdens in such a situation. Not only are they still forced to endure or challenge pre-existing workplace issues such as gender bias, discrimination, sexual harassment, and other inequalities, but they make up 75% of the health workforce. Female doctors are already depression-prone, and suffer more burnout and report more suicidal thoughts relative to their male counterparts. In addition, they carry out much more work unrelated to their professional duties, such as parenting and caregiving, compared to men – on average, this is 2.5 times greater.

Review of studies on HCW burnout reveals risk factors

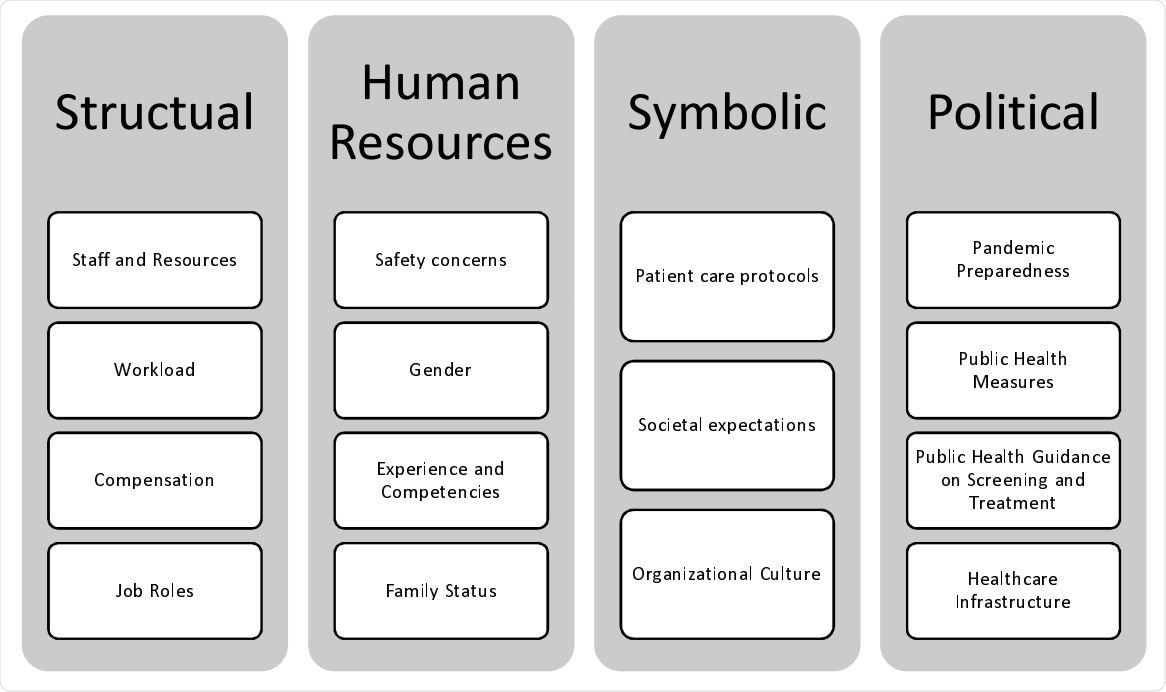

The scientists looked at 47 studies from all over the world. They found that stress and burnout in female HCWs were primarily because of poorly structured organizations, roles at work, and policies. In over 40% of cases, the lack of adequate resources was cited, including not having access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and having too few staff. Also, those directly caring for COVID-19 patients had increased stress and burnout in 43% of the studies. In about 38% of studies, HCWs were found to have a higher burden at work, with more COVID-19 patients to care for, but without enough compensation.

Two-thirds of HCWs said they were concerned about passing on the infection to their family, and they were worried about their own safety as well. Over a third of women were at high risk for stress and burnout. Women who were young, had no family, or had young children to care for were more likely to be emotionally stressed and experienced burnout. Inexperienced HCWs, and those who felt they were not capable of the work demanded of them in caring for COVID-19 patients, were at higher risk.

Over a quarter traced their burnout to their organization's culture, patient care protocols, and their interactions with society at large. Patient care protocols failed to clearly define the steps, especially when related to poor infection care guidelines, which were repeatedly identified as stress triggers. When peers, managers, and organizational leaders were supportive of their work, women HCWs were less likely to suffer burnout.

Triggers of Stress and Burnout during COVID-19

Idolization coupled with persecution

One phenomenon is the universal idolization of HCWs in the mass as heroes who are combating the epidemic on the frontline, with a paradoxical stigmatization and avoidance of them at personal level due to their presumed contagion risk. The first attitude imposed a higher burden of expectations on HCWs, increasing their feeling of moral responsibility and stress as they tried to meet such expectations. On the other hand, their social isolation led to immense emotional turmoil. Such burdens were only increased by social distancing, in keeping with government guidelines.

Public and governmental responsibility

The government and public authorities also contributed to burnout in other ways. Public health failures such as non-preparedness for a pandemic, as well as failures to prepare official guidelines and set up facilities for the screening and treatment of the disease, led to increased stress and burnout in young women.

Supportive measures

Less than 40% of the studies dealt with measures that could make women workginh in healthcare feel more supported. In about a third of the studies, individual well-being and resilience were addressed. These included regular exercise, mental health support, and faith-based activities, as well as hobbies.

In a fifth of studies, the researchers promoted interventions at the organizational level, such as changing the work type or schedule, improving communication about work policies, providing physical resources such as PPE, offering training relating to the proper management of the disease, and financial support. More down-to-earth interventions included providing rest areas, food, and resiliency training. No evidence was offered that any or all of these measures were useful, however, but some studies did show that undesirable coping mechanisms were at work, such as avoidant coping and substance use.

Severe dearth of data

There is a severe shortage of information on how race, culture, profession, and leadership affect the risk of stress during the pandemic. For instance, it is astonishing and tragic that fully a third of female nurses who have died during this period in the USA are Filipino. There is also little data on how burnout affects HCWs at different levels of the organizational hierarchy.

Policies such as the US Families First Coronavirus Response Act allowed employers to exclude HCWs from the 80 hours of paid sick leave that could be availed of citing COVID-19-related benefits. This discriminatory act caused much anxiety and stress among people in these professions. Not much is known about how such stress and burnout affect the quality of care or patient safety, absenteeism, and even long-term decisions about whether to work, especially among female HCWs.

Conclusion

The researchers concluded that much remains to be known about how COVID-19 affected female HCWs. Such data is important in quantifying, describing and eventually preventing female burnout in the health and allied professions. National health organizations should gather more data in this area to enable sound conclusions to be drawn and improve health for women in the healthcare workforce.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources