A recent study has found that extracellular vimentin can bind to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein in vitro, and antibodies against vimentin can decrease virus infectivity by up to 80%. This suggests vimentin could aid the virus’s binding to host cells and help in infection.

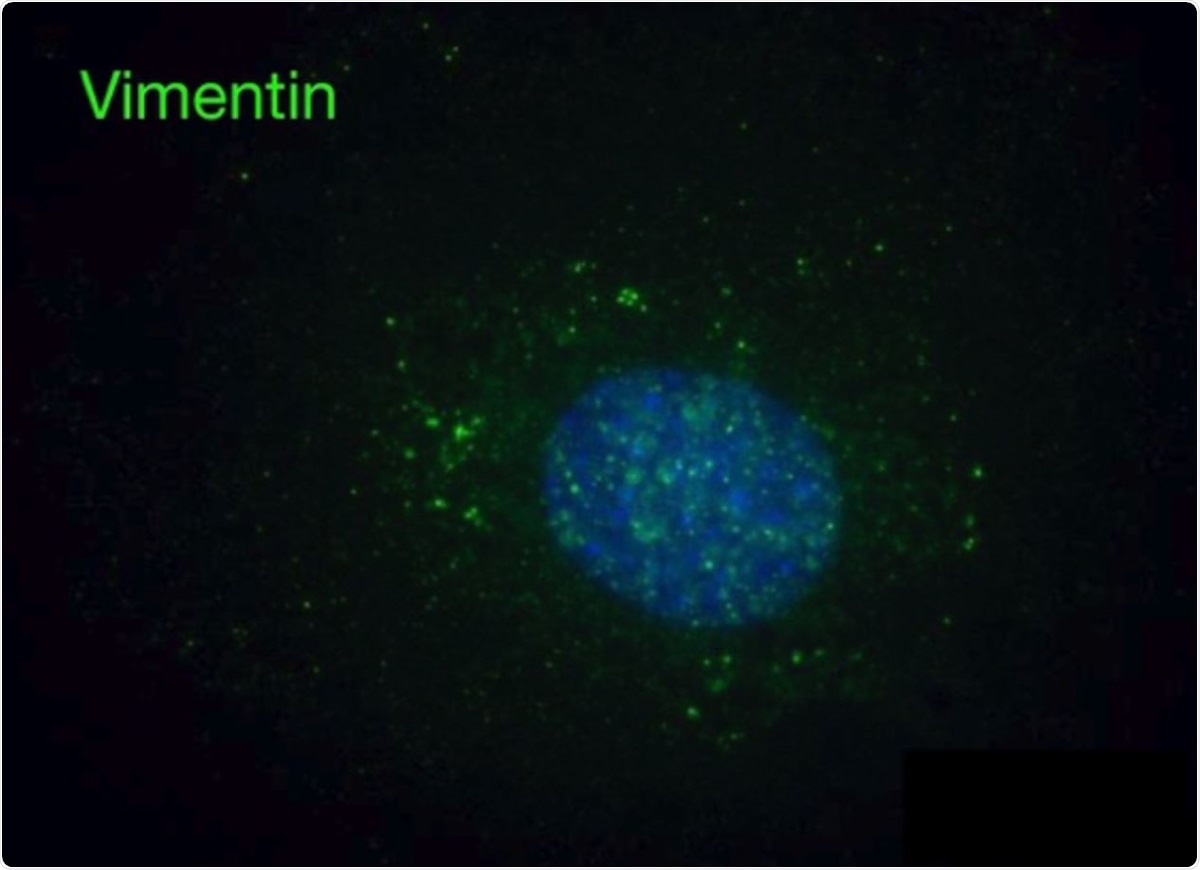

Immunofluorescence images of vimentin-null mEF staining positive for extracellular vimentin after exposure to supernatant of NETosis-activated neutrophils, indicating the acquisition of extracellular vimentin by cells that do not express vimentin.

SARS-CoV-2 infects humans by binding to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). ACE2 is expressed in the lungs, kidneys, and the gastrointestinal tract. However, studies suggest ACE2 alone is not sufficient for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

ACE2 expression is low in the respiratory system compared to other organs. Although the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a strong binding affinity to ACE2, its binding-on rate is slow. In vitro tests show the half time for maximum binding is around 30 s at concentrations much higher than those found in vivo. This suggests there is another important receptor that helps the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to host cells. Some possible co-receptors include neuropilins, heparan sulfate, and sialic acids.

There are several studies supporting the possibility of cell surface vimentin, an intermediate filament protein, aiding the binding and uptake of different viruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Vimentin is secreted into the space outside cells and can be produced by different types of cells.

Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, another enzyme facilitation SARS-CoV-2 binding to host cells, is high is nasal cells, which also have vimentin. Thus, it is likely that cell surface vimentin could be a co-receptor for SARS-CoV-2.

Vimentin binds to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

In a study published in the bioRxiv* preprint server, researchers report that vimentin can act as a co-receptor for SARS-CoV-2 binding to the host cell, and antibodies against vimentin can block up to 80% of cellular uptake of SARS-CoV-2.

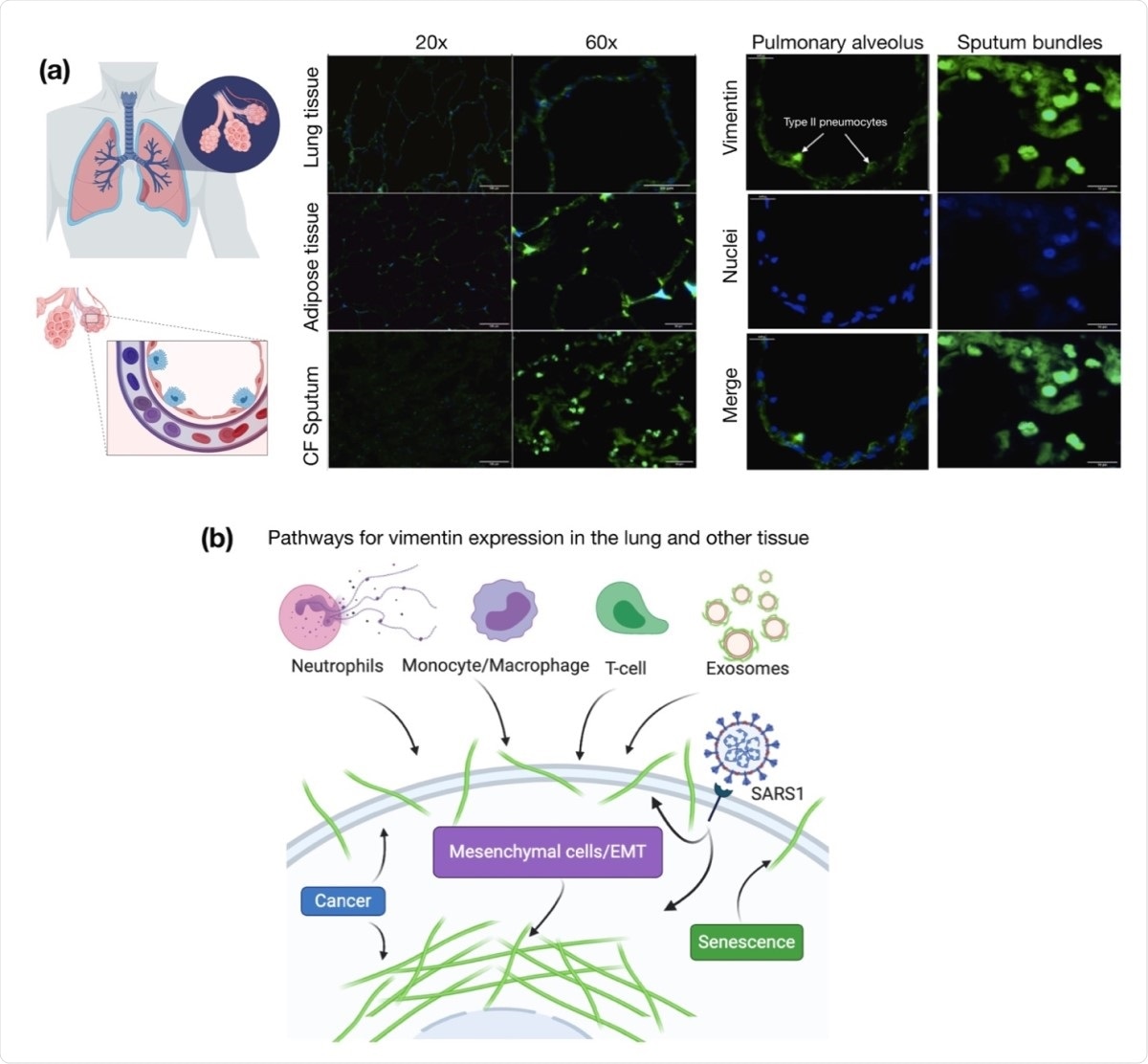

Presence of extracellular vimentin in human lung, airway fluids, and fat tissue. (a) Positive staining for extracellular vimentin (green) in human lung, fat tissue, and sputum obtained from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Vimentin appears on the apical side of type I and type II pneumocytes. DNA stained with DAPI. (b) There are numerous internal and exogenous pathways by which vimentin may be found in lung epithelia and other tissues, in either intracellular or cell surface forms (shown as green filaments). Vimentin is expressed directly by mesenchymal cells, cells having undergone EMT, cancer cells, senescent fibroblasts, and interestingly by cells bound and infected by the SARS virus (see Table 1). Exogenous sources of vimentin are largely related to immune response and tissue injury in the form of vimentin exported by neutrophils, Tlymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and exosomes. Schematics generated with Biorender.com.

Vimentin is present in nasal and lung epithelial cells, and it may also be present in the extracellular space of the lungs and other tissues. Using an anti-vimentin antibody and staining, the authors confirmed the presence of vimentin in lung cells and in the extracellular space of the lungs. They also found vimentin in human adipose tissue (body fat); this is a particularly pertinent finding, given the high-risk status of obese individuals to severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The authors found that virus-like particles (VLPs) coated with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein could bind to human vimentin, expressed by bacteria. Combining dynamic light scattering and atomic force microscopy, they found that upon adding vimentin, the size of the VLPs increased, indicating vimentin can bind to SARS-CoV-2. There was no change in size of the VLP upon addition to DNA strands, showing that vimentin binds specifically to SARS-CoV-2.

The team then tested the effect of several antibodies against vimentin on the virus infectivity to human kidney and lung epithelial cell lines expressing ACE2. They used antibodies like Pritumumab, a human-derived IgG antibody, a chicken polyclonal antibody, another human-derived antibody targeting the vimentin C-terminal, and a rabbit monoclonal antibody against the N-terminal.

When they exposed the epithelial cell to Pritumumab prior to SARS-CoV-2 VLP infection, the researchers found a decrease in infectivity, with a maximum reduction of 60%, with increasing concentration of Pritumumab. The polyclonal antibody decreased infection by 80%, while the rabbit antibody was not effective in preventing infection. This suggests antibodies targeted to the vimentin C-terminal were more effective than those targeting the N-terminal.

Vimentin may facilitate SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2

The results suggest extracellular vimentin can bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and help the virus infect host cells. The authors also found that even cells that do not express vimentin can get surface vimentin from the extracellular regions by a process called neutrophil NETosis. This is a defense mechanism in hosts, where neutrophils eject large DNA webs that can trap bacteria.

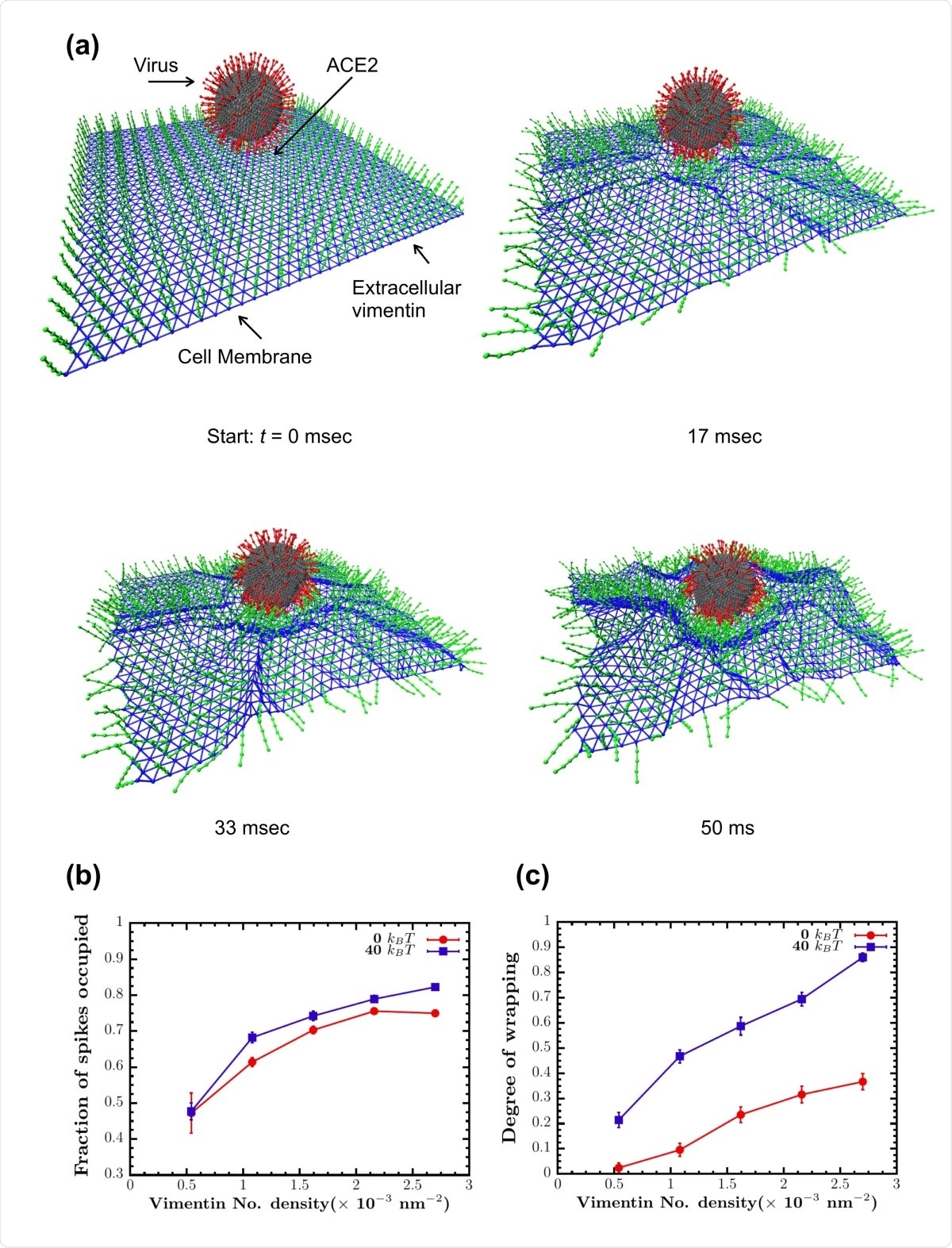

Vimentin’s involvement in spike 2-ACE2 interactions. (a) Cell surface vimentin acts as a co-receptor that enhances binding to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in either direct fusion or endocytic pathways to enhance wrapping and endocytosis of the virus. A molecular dynamics simulation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus at an elastic shell membrane shows that binding of extracellular vimentin with the virus spike protein facilitates wrapping of cell membrane around the virus. Both the fraction of spikes bound to surface vimentin (b) and the degree of membrane wrapping (c) increases as the number density of surface vimentin increases. Finite membrane bending rigidity (40 kBT, blue squares) enhances wrapping compared to the case without bending rigidity (0 kBT, red circles).

They found mouse-embryo fibroblasts that did not have vimentin turned positive for vimentin when exposed to neutrophils with vimentin.

Because of the slow rate of spike protein-ACE2 binding, virus interaction would be greatly increased if the virus was first immobilized by a fast binding event. The binding rate of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to vimentin is likely higher than that of the virus to ACE2, although the rates still need to be measured.

Thus, extracellular vimentin would serve as a critical co-receptor, binding and engaging with the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the surface of the cell membrane, enhancing its delivery to the ACE2 receptor,” write the authors.

Understanding how vimentin is expressed and transported will therefore be important in treating viral infections and could be a novel target for SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Suprewicz, L. et al. (2020). Vimentin binds to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and antibodies targeting extracellular vimentin block in vitro uptake of SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.08.425793, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.08.425793v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Suprewicz, Łukasz, Maxx Swoger, Sarthak Gupta, Ewelina Piktel, Fitzroy J. Byfield, Daniel V. Iwamoto, Danielle Germann, et al. 2021. “Extracellular Vimentin as a Target against SARS‐CoV‐2 Host Cell Invasion.” Small 18 (6): 2105640. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202105640. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smll.202105640.