Researchers at the University of North Carolina and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Washington have developed a way to evaluate vaccines' long-term efficacy against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) – the agent that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The team conducted a series of simulation studies mimicking the trial of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine BNT162b2 to investigate the duration of protection under various blinded and unblinded crossover designs.

Dan-Yu Lin and colleagues recommend the "rolling crossover" design, where participants that were previously placebo recipients are vaccinated in a timely manner.

Under this design, the team's approach can be used to determine when a booster vaccination would be required. This information is also useful for modeling the impact of COVID-19 vaccines at the population level.

The approach only requires minimal assumptions and can be applied to both blinded and unblinded crossover designs, irrespective of the length of further follow-up.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

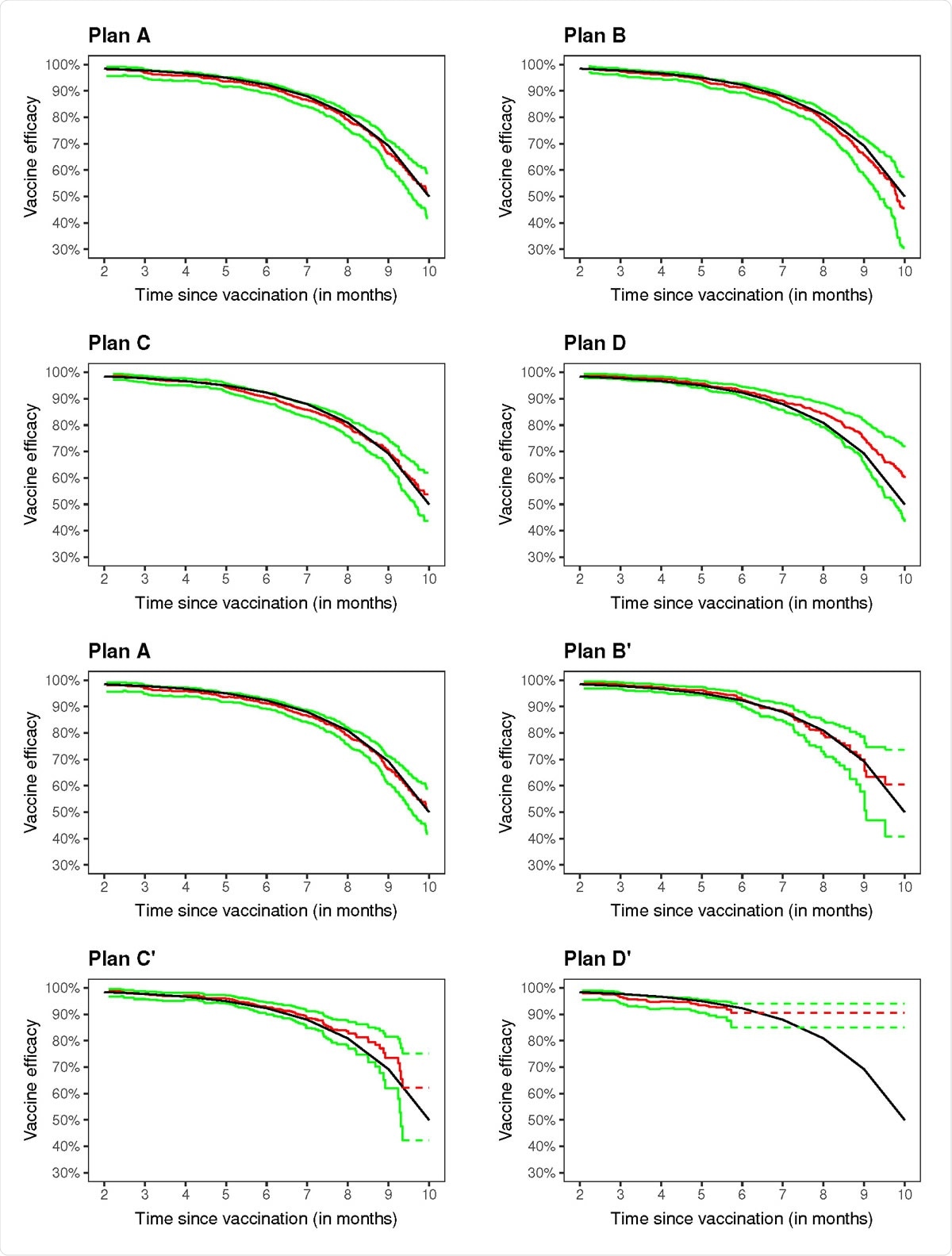

Estimation of vaccine efficacy in a clinical trial with no crossover (A), three blinded crossover (B{D), and three unblinded crossover (B'{D'): the black curve pertains to the true value, the red curve to the proposed estimate, and the green curves to the 95% con�dfience intervals.

Interim trial results only provide data on short-term efficacy

The large-scale administration of vaccines that provide long-term protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection would help bring the COVID-19 pandemic to a halt.

Interim results from a number of phase 3 clinical trials have demonstrated vaccine efficacy that far exceeds the thresholds required by the World Health Organization and US Food and Drug Administration.

"However, those trials have been underway for only several months, and the data they have collected thus far can only speak of short-term vaccine efficacy," says Lin and colleagues.

Given that vaccine efficacy can wane over time as immune memory declines and viral antigens change, it is crucial to establish how long protection lasts and when booster doses may be required, says the team.

How might long-term vaccine efficacy be estimated?

Once a vaccine receives Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), placebo-controlled data is still collected in ongoing trials for as long as possible, but at some point, all placebo recipients should be offered the vaccine.

Under one approach called "rolling crossover," placebo participants are vaccinated at around the same time that general population members of the same priority tier are vaccinated.

"Under this design, placebo participants are vaccinated at different times, with the timing of vaccination depending on enrollment characteristics that define their priority tier," writes Lin and colleagues. "Because of staggered enrollment, existing statistical methods do not produce valid estimates of time-varying vaccine efficacy, even if the placebo group is maintained throughout the study."

The researchers have now shown how to estimate long-term vaccine efficacy in trials that apply this staggered vaccination under both blinded and unblinded crossover strategies.

The method fully adjusts for staggered enrollment, change of background incidence over time, and the prioritization of higher-risk individuals during the crossover process.

How effective is the approach?

The approach provides an unbiased estimation for the entire curve of placebo-controlled vaccine efficacy as a function of time passed since vaccination, up to the point where most placebo recipients have been vaccinated.

In a series of simulation studies of the BNT162b2 vaccine trial, the researchers considered 40,000 participants who had been randomly assigned to vaccine or placebo over the course of 4 months. Following approval of the vaccine during the 5th month based on interim results, participants underwent staggered vaccination over the following 5 months.

The outcome of interest was time to development of symptomatic COVID-19.

The estimated curve of time-varying vaccine efficacy could be used to determine when a booster vaccination would be required to ensure sustained protection. This information is also important for mathematical modeling of the impact COVID-19 vaccines have at the population level.

What does the team advise?

To ensure that follow-up data is of high quality, the crossover should be blinded, with placebo participants receiving vaccines and vaccine participants receiving placebo at the point of crossover, says the team.

While unblinded crossover is less expensive and less complicated, it can result in differential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 between the original vaccinees and the placebo recipients crossing over. This can then bias the efficacy estimates, a problem that could be avoided by only assessing follow-up data from blinded crossover.

However, ignoring the unblinded follow-up data can also reduce the accuracy of the long-term efficacy estimate.

How about using both types of data?

"We suggest estimating vaccine efficacy in two ways, one using all follow-up data and one using only blinded follow-up data, and then comparing the two results," say the researchers. "Another solution is to apply our methods to all follow-up data, but perform a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the results to potential unmeasured confounding caused by unblinding of trial participants."

Lin and colleagues demonstrate how a best-practice general methodology can be applied in epidemiological studies to perform this sensitivity analysis.

Specifically, the methodology can be used to assess how strong unmeasured confounding would need to be to explain away the observed vaccine efficacy. It can also provide a conservative estimate of efficacy that accounts for unmeasured confounding.

Finally, "our approach requires minimal assumptions and is applicable to both blinded and unblinded crossover plans, with any length of additional follow-up," concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources