The spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected almost a hundred million people, with over two million deaths being attributed to this illness over the past 12 months or so. The only means to counter this so far has been through non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). The lockdown has been the most stringent and disruptive form, with severe economic, social, educational, and psychological consequences.

Now that the pandemic has resurfaced in a more infectious form in many countries, the efficacy of these measures must be fine-tuned to contain the pandemic without causing undue suffering apart from the viral illness itself. A new preprint on the medRxiv* server describes an epidemiological model, SIR-SD-L, to measure the lockdown's effectiveness and its relaxation.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

The model

The researchers developed the model parameters to include the introduction of new people after removing restrictions on mobility and identifying the parameters that affect viral spread. The model also integrates social distancing parameters implemented according to the progression of the infection.

Reducing the number of social contacts reduces the reproduction number R0 of the virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Since social distancing changes the pattern of contacts, these changes should be implemented in the model, as shown in earlier models.

However, the current model goes further in considering the behavioral changes occurring due to an increase in the number of infections and higher case reporting, along with social distancing guidelines and mandates. These factors cause a change in the viral transmission rate. In fact, the rate of spread depends negatively, in part, on the total number of infections and directly on the size of the susceptible population over time.

Moreover, the model includes the variations in disease spread based on the number of current infections, described concerning the total susceptible population. The model can help predict the rate of increase of the susceptible population based on the rate of infections.

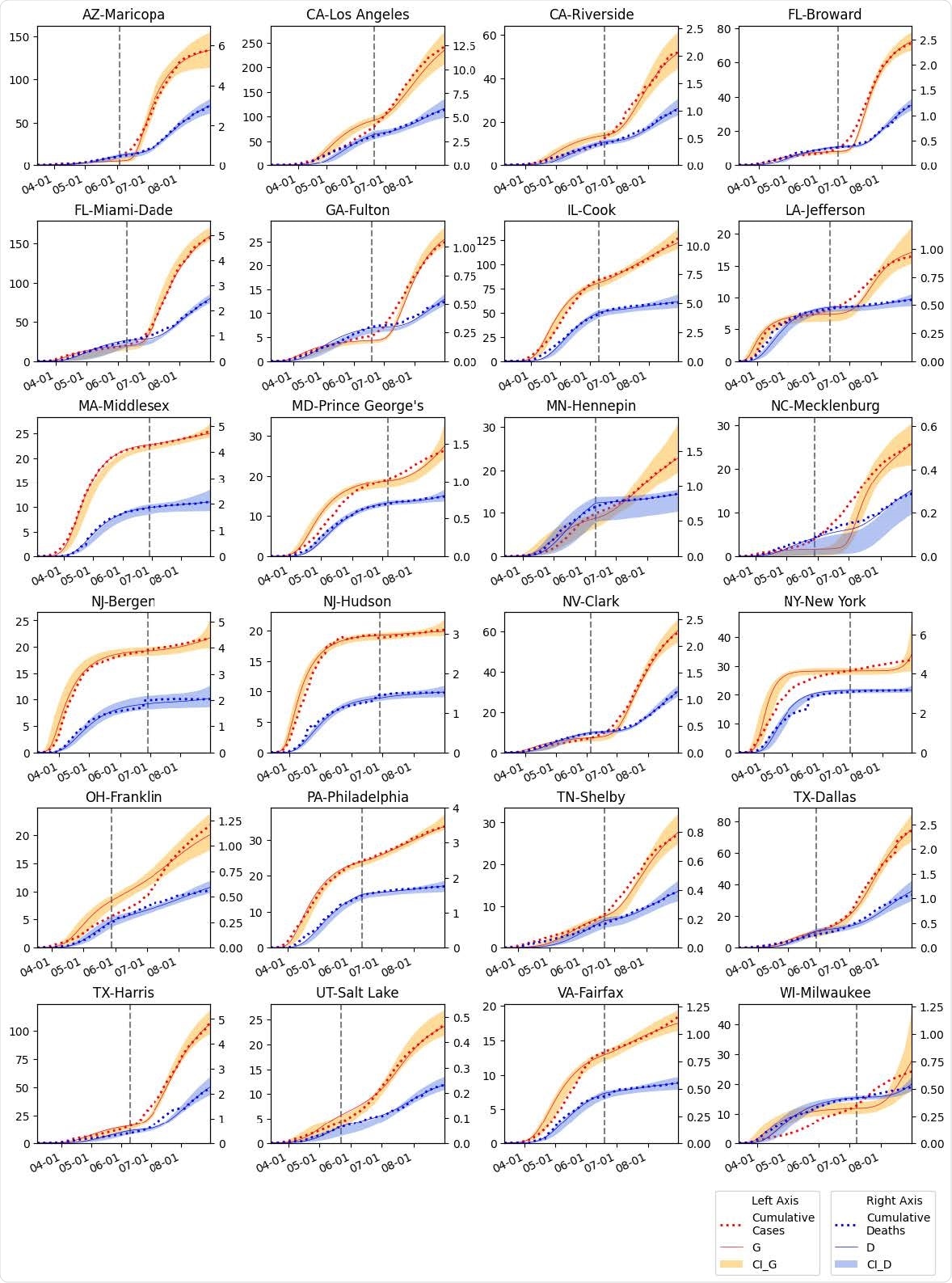

The SIR-SD-L model fitted for 24 US counties. Cumulative infection numbers (G) and deaths (D) are modeled for each of the counties. Range of intervals (95% CI) are illustrated for both G and D. The vertical dotted line represents the reopen date for each county.

Validation in 24 counties

The model was tested for validity using data from 24 counties in several US states on the rate of growth of infection, the number of hospitalizations, and deaths and classification of relaxation of lockdown policies after the first lockdown.

The researchers used a PIR ratio, which is below 1 for any county with mandatory social distancing, and where bars, restaurants, and other social spaces were not reopened immediately. Otherwise, it is above 1. A lower PIR meant fewer active cases or a lower number of susceptible people at the time of reopening.

Thus, the timing is crucial when determining when to reopen a locked-down county. A slower relaxation of the population can help reduce the second peak of infections.

The researchers illustrated their case by showing that a delay of one week in reopening a county could have reduced the total number of infections, and even more significant if it was delayed by a month. They used a term called the delay ratio, the ratio of new infections post-reopening, after a delay of one month, to the new infections after the actual date of reopening. The reduction comes to 42%, though the exact extent of lowering the caseload may probably be less if the assessment period is longer.

Additionally, the growth of infection rates in these counties was evaluated against the guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) and compared with delayed lockdown relaxation strategies.

What did the study show?

The researchers found that the primary factors driving the resurgence of the pandemic include social distancing, active infections, and susceptible populations. They concluded that lockdown relaxation parameters should consider the current level of infectious people and the susceptible population. In contrast, currently, only the rate of new infections is considered when deciding whether to continue or remove the lockdown.

Such a model can provide a reliable estimate for the number of active infections and the number of susceptible people as a basis for safe reopening. The rate of relaxation for each population segment should also be included as it also affects the pandemic's resurgence. The exact effect of the relaxation on the second wave's size and timing can be estimated from this model.

The researchers illustrated their case by showing that a delay of one week in reopening a county could have reduced the total number of infections, and even more significant if it was delayed by a month. They used a term called the delay ratio, the ratio of new infections post-reopening, after a delay of one month, to the new infections after the actual date of reopening. The reduction comes to 42%, though the exact extent of lowering the caseload may probably be less if the assessment period is longer.

In counties with a slow increase in infections in the initial phase, the existing approach may seriously mislead policymakers, causing social distancing to be dismissed. This, in turn, may contribute to the massive resurgence of COVID-19. The study brings out the large difference between counties where social distancing is followed, including strict mask use and limitations on the number of people in a public space and those without such restrictions.

Thus, the timing is crucial when determining when to reopen a locked-down county. A slower relaxation of the population can help reduce the second peak of infections.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.