Coronaviruses can infect both animals and humans. Coronavirus infections are common, and some strains are zoonotic, which means they can be transmitted between animals and humans.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), emerged in Wuhan City, China, in late December 2019. Though the exact animal reservoir of the virus is yet to be identified, scientists believe the virus came from a horseshoe bat and jumped to an intermediate host before making its way to the human population.

Researchers at the Beijing Computational Science Research Center and Peking University analyzed sequences of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) proteins from 16 mammals and predicted the structures of ACE2- receptor-binding domain (RBD) complexes.

The team has found that the ACE2 proteins of bovine, cat, and panda form a robust binding with the RBD. Meanwhile, the ACE2 proteins of rats, horseshoe bat, pig, horse, mouse, and civet interact weakly with RBD.

The study suggests that those animals with strong binding ACE2 to RBD are more likely to be infected or become hosts of the virus.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Zoonotic infections

Over the past years, several zoonotic events have occurred across the globe. These include zoonotic influenza, such as the H1N1 flu or swine flu, salmonellosis, West Nile virus, plague, rabies, Lyme disease, and emerging coronaviruses, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and SARS-CoV-2, among others.

Some coronaviruses cause cold-like illnesses in people, while others cause illness in some animals, such as cattle, bats, and camels. Meanwhile, some coronaviruses, such as feline and canine coronaviruses, infect only animals. However, zoonotic spillovers can happen, just like in the current coronavirus pandemic, which has now spread to 192 countries and territories. To date, there are more than 104 million COVID-19 cases globally. Over 2.25 people have died from the infection.

The study

The current study, published on the pre-print server bioRxiv*, wanted to determine which animals could be potential hosts for SARS-CoV-2 so as to help prevent future outbreaks.

ACE2 is a protein on the surface of many cell types. It is an enzyme that generates small proteins by cutting up the larger protein angiotensinogen, which then regulates functions in the cell.

Using the spike-like protein on its surface, the SARS-CoV-2 virus binds to ACE2. Once the spike protein, particularly the RBD, binds with the ACE2, the virus can enter the human cell and cause infection.

Since ACE2 is widely seen in mammals, it is crucial to investigate RBD interactions and the ACE2 of other mammals.

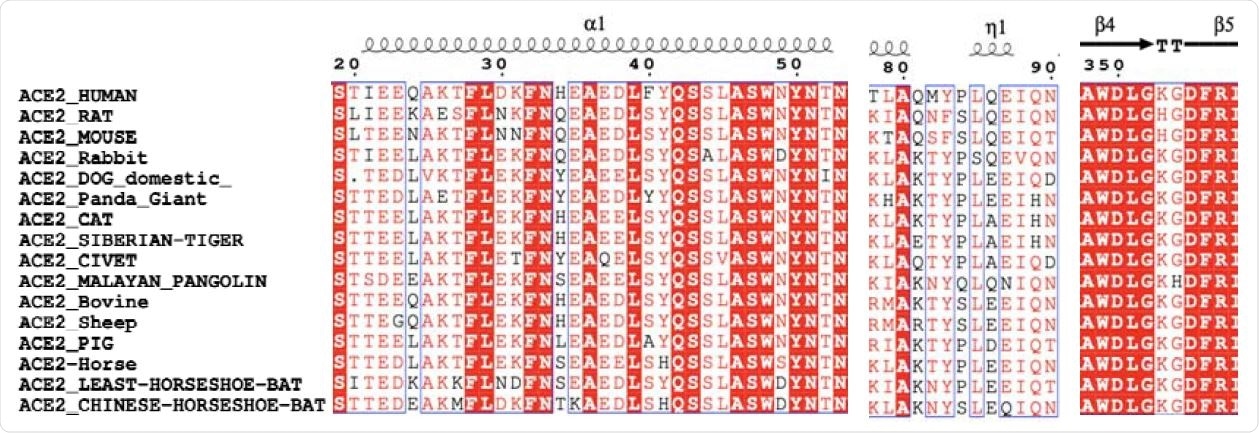

To arrive at the study findings, the researchers analyzed the sequences of ACE2 proteins from 16 mammals and predicted the structures of ACE2-RBD complexes. The team studied the sequence, structure, and dynamics of these complexes, providing valuable insights into the interactions between ACE2 and RBD.

The comparison for the key residues at the binding interfaces after multiple sequence alignment analysis.

The ACE2 sources selected in the study included humans, bovine or cow, cat, Chinese Horseshoe bat, dog, giant panda, horse, Least Horseshoe bat, Malayan pangolin, mouse, Palm civet, pig, rabbit, rat, sheep, and the Siberian tiger.

The team obtained the ACE2 sequences from the NCBI and uniport databases. They modeled structures for 15 mammalian ACE2 proteins. Then, the SARS-CoV-2 RBD and ACE2 complexes were assembled.

The team computed and visualized the electrostatic potential maps at the ACE2-RBD complex interfaces. Meanwhile, they also carried out molecular dynamics simulations of ACE2-RBD complexes.

The study findings showed that cats, pandas, bovine or cows, and humans form strong interactions with the RBD, while the ACE2-RBD are weaker in dogs, Siberian tigers, Malayan pangolins, sheep, and rabbits. In mice, civets, horses, rats, pigs, and least Horseshoe bats, the interactions were much weaker. Further, the ACE2 of bovine and sheep manifest high sequence identities to human ACE2.

"This study provides a molecular basis for differential interactions between ACE2 and RBD in 16 mammals and will be useful in predicting the host range of the SARS-CoV-2," the study authors concluded. Knowing the host range of the novel coronavirus can help predict and prevent future outbreaks.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Lupala, C., Kumar, V., Su, X., and Liu, H. (2021). Computational insights into differential interaction of mamalian ACE2 with the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429327,

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Lupala, Cecylia Severin, Vikash Kumar, Xiao-dong Su, Chun Wu, and Haiguang Liu. 2021. “Computational Insights into Differential Interaction of Mammalian Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 with the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domain.” Computers in Biology and Medicine, November, 105017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105017. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010482521008118?via%3Dihub.