The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has claimed well over 2.4 million lives, but its long-term sequelae are still being identified. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) produces an infection that may be associated with a wide spectrum of disease, from asymptomatic to critical or terminal respiratory failure or multi-organ dysfunction.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Neurological symptoms in SARS-CoV-2 infection

SARS-CoV-2 primarily affects the respiratory organs, but in about a third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, neurological manifestations are present. These include anosmia or dysgeusia, delirium, impaired consciousness, seizures, or psychosis. Some patients also develop Parkinsonism.

Neurological symptoms may be due to brain infection by the virus or because of virus-induced immune cell activation. More evidence is required to arrive at a conclusion on this matter in human SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The long-term effects on the central nervous system (CNS) following this infection, even with mild or moderate COVID-19, are poorly understood, though they are probably present in most patients.

Study aims

In order to explore this, the current study was performed in a controlled design on two macaque species, the rhesus macaques and cynomolgus macaques.

After inoculation with SARS-CoV-2 into the monkeys by a combination of intratracheal and intranasal routes, the researchers found that viral RNA was found in both tracheal and nasal swabs for up to ten days. All the monkeys had mild to moderate disease.

Increased brain metabolism

The researchers also followed up the animals with weekly tracer PET-CT scans of the brains after the virus was no longer found in the respiratory samples. They found that two of four monkeys showed increased tracer uptake in the pituitary gland at many points.

Tracer uptake is a proxy for metabolic activity. The metabolic activity of the pituitary is typically similar to brain background metabolism.

In one animal, tracer uptake increased from day 8 to the last scan at day 35. This indication of higher metabolic activity could have been due to direct infection of the pituitary gland, or an indirect effect of pituitary inflammation, or the result of hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. Interestingly, no COVID-19 patient with active infection has been found to have low cortisol levels indicative of low pituitary function.

Viral RNA in brain tissue

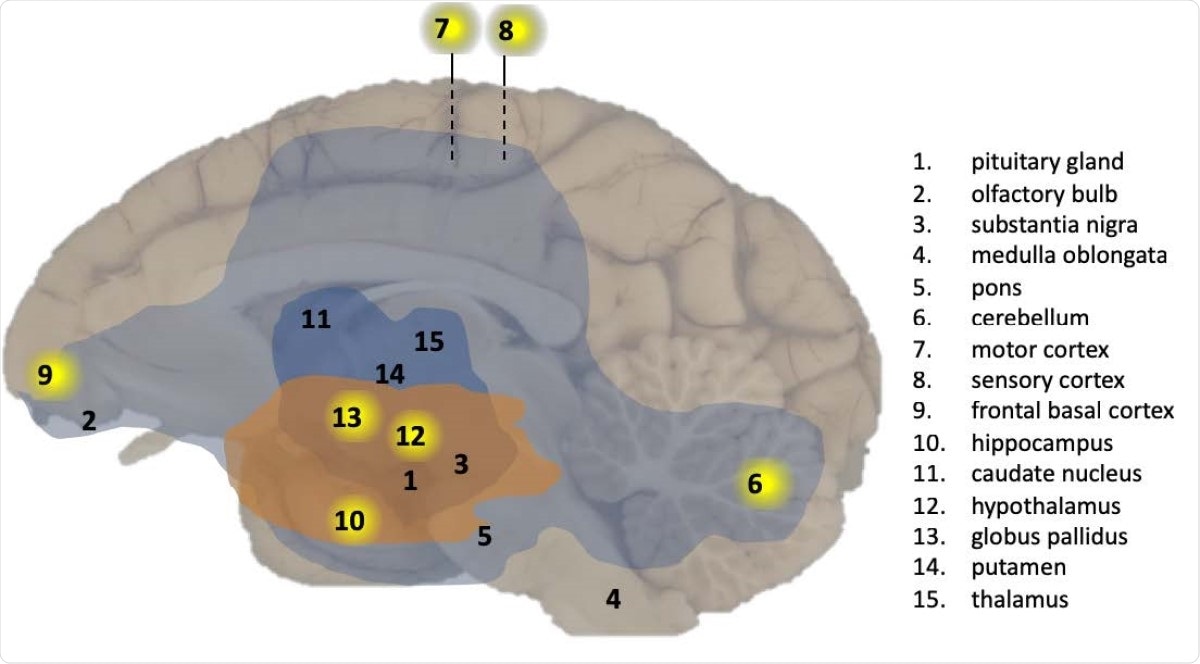

After euthanizing the animals at 5-6 weeks post-infection, the researchers found that viral RNA was detectable (using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction, RT-qPCR) in many parts of the right brain in the cynomolgus macaques.

These included the cerebellum, the medial motor cortex, sensory cortex, and the basal ganglia. The pituitary, olfactory bulb, substantia nigra, medulla oblongata, pons, nucleus caudatus, and putamen did not show immunological markers for the viral RNA.

No evidence of viral replication

Subgenomic RNA was not present, indicating that viral replication was not occurring in the brain at that point. Viral antigens were also not detected in any animal.

Inflammation of brain tissue

Inflammation was observed in the brains of all infected macaques. T cell infiltration was also present in the brain parenchyma, which may indicate that T cells crossed the blood-brain barrier following infection.

Microglial activation was also present in different brain areas, notably the pituitary and the olfactory bulb, but at a low level. B lymphocytes were not found, neither was there any evidence of brain ischemia or necrosis.

Lewy bodies

The macaque brain tissue also contained Lewy bodies, or a-synuclein deposits, which, in humans, is linked to Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia. These were found in the midbrain of all rhesus macaques and one aged cynomolgus macaque, but none of the controls.

Overview of CNS effects by SARS-CoV-2 exposure in a macaque brain. Presence of viral RNA was investigated in multiple regions of the brain as indicated by the numbers. Viral RNA-positive regions in cynomolgus macaque C3 are indicated by a yellow background. The analysed brain regions are indicated with a number. Brain areas with T-cells (CD3+) and activated microglia (Mamu-DR+) are shown in light blue (mild expression) and dark blue (moderate expression), respectively. Brain areas with Lewy bodies (a-synuclein+) are shown in orange.

What are the implications?

This shows that SARS-CoV-2 drives inflammation in the macaque brain. The presence of viral RNA also indicates that the virus is neuroinvasive.

Critically ill COVID-19 patients have shown some signs of neuropathology. In contrast, the macaques in this study had only mild or moderate infection symptoms, but brain involvement was present.

The route of entry of the virus to the brain could be the olfactory bulb or other neuronal pathways, such as infected sensory or motor neurons, thus reaching the pituitary, which has the entry receptor for the virus, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

In fact, in all the infected macaques, there was evidence of immune activation in the olfactory bulb, as shown by the presence of activated microglia or T cells.

If the virus is transported within neurons, it could also explain the development of Parkinson-like symptoms. The virus could also reach the substantia nigra, connected to Parkinson’s disease, by retrograde transport.

This region is in the ventral midbrain, where Lewy bodies were found in the macaques. These accumulations of misfolded protein within inclusion bodies are associated with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia in humans.

Based on their findings, the researchers ask whether they have predictive value for the long-term development of these disorders in COVID-19 patients, even if the infection was mild or even asymptomatic.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.