Researchers in the UK have conducted a study that may explain why children who become infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) do not generally develop severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The team – from Public Health England, the University of Birmingham, and various NHS Foundation Trusts across England – says a key finding of the study was that the magnitude of the adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 was significantly increased among children (aged 3 to 11 years), compared with among adults (aged 20 to 71 years).

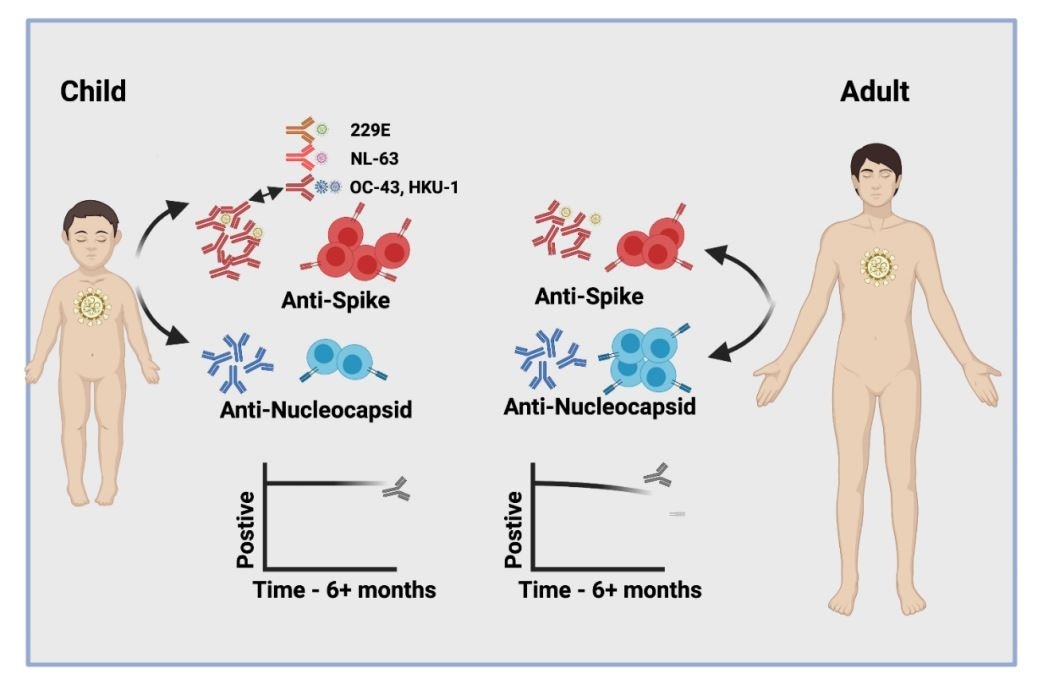

Another striking feature was that SARS-CoV-2 infection among children doubled antibody titers against four other types of human coronaviruses that frequently cause the common cold – a pattern that was not observed in adults.

The cellular immune response to the viral spike protein was also more than twice as strong among children compared with among adults. The spike protein is the surface structure the virus uses to bind to and infect host cells.

Importantly, all children retained high antibody titers and cellular responses for more than 6 months following infection, while a relative waning of antibody titers was observed for adults.

“We demonstrate a markedly different profile of immune response after SARS-CoV-2 infection in children compared to adults,” writes Shamez Ladhani and colleagues.

The researchers say the findings have potential implications for understanding immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children.

“Such information on the profile of natural infection will help to guide the introduction of vaccination regimens into the pediatric population,” they add.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

Children generally develop mild or asymptomatic disease

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

In children, SARS-CoV-2 infection generally only causes mild or asymptomatic disease rather than the severe disease that is more commonly observed among adults.

However, the biological basis for this is unclear and researchers are keen to better understand the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 among children.

One potential determinant of this difference between children and adults may be the timing of exposure to other endemic human coronaviruses (HCoVs) that exist aside from SARS-CoV-2.

These include the viruses OC-43 and HKU-1, which share 38% and 35% amino acid sequence identity with SARS-CoV-2, as well as the more distantly related coronaviruses NL-63 and 229E, that each share around 31% identity.

These coronaviruses frequently cause the common cold in children and antibody seroconversion typically occurs before the age of five.

“Recent HCoV infection might pre-sensitize children against SARS-CoV-2 infection,” says Ladhani and colleagues.

Furthermore, mass vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is now being rolled out in many countries and vaccine trials in children are currently underway.

“It is, therefore, imperative to understand the baseline profile of SARS-CoV-2 specific immune responses in children to inform vaccination strategy,” writes the team.

What did the researchers do?

The team comprehensively assessed the convalescent humoral and cellular immune response among 92 children (aged 3-11 years; median age 7 years) and 155 adults (aged 20-71; median age 41 years) who participated in the SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in the schools (sKIDs) study.

The researchers determined the participants’ serological responses against the viral spike protein, the spike receptor-binding domain (RBD), the spike N-terminal domain (NTD), and the nucleocapsid (N) protein that is essential for packaging the viral genome into new virions.

What did they find?

In total, 47% of children and 59% of adults were found to be seropositive, with each age group exhibiting broadly similar antibody responses against the viral proteins.

However, mean antibody titers against all four proteins were higher among the children, particularly those produced against the NTD and RBD. The antibody titers were 2.3-fold and 1.7-fold higher for these domains, although the results did not reach statistical significance.

Next, the team compared the antibody titers generated against the HCoVs OC-43, HKU-1, NL-63 and 229E in SARS-CoV-2 seronegative and seropositive children and adults.

This revealed a 1.2- to 1.4-fold increase in antibody titers against HCoVs among the seropositive versus seronegative adults, compared with a 1.5 to 2.3-fold increase among seropositive versus seronegative children.

These increases among the children reached statistical significance for OC-43 and HKU-1 – the coronaviruses most closely related to SARS-CoV-2.

Using protein domain pre-absorption, the researchers discovered that the children’s increased antibody response to these seasonal coronaviruses was partly due to cross-recognition of subunit 2 of the spike protein, pointing to a broad humoral response that was not observed in adults.

What about the cellular response?

The magnitude of the T cell responses against the spike protein was also 2.1-fold greater among children than among adults.

Cellular responses to the spike were also observed in more than half of the seronegative children, suggesting pre-existing cross-reactive responses or sensitization to SARS-CoV-2.

Children retain humoral and cellular immunity for at least 6 months

Importantly, all children retained high humoral (antibody) immunity for at least 6 months after infection, while 7% of adults who were previously seropositive failed to show significant humoral responses after 6 months.

Cellular immune responses were also detectable in 84% of children and 79% of adults at least 6 months post-infection. The magnitude of the spike-specific response remained higher among children than among adults.

“Children thus distinctly generate robust, cross-reactive and sustained immune responses after SARS-CoV-2 infection with focused specificity against the spike protein,” writes Ladhani and the team.

The findings may help to explain the excellent clinical outcomes in children

The researchers say this profile of cross-reactive antibody and cellular responses in children may help to explain the excellent clinical outcomes in this group.

“These data provide encouragement that immunity generated in childhood may provide longer-term protection in the light of increasing concerns that SARS-CoV-2 will become an endemic infection,” they write.

“Furthermore, they will help to guide the introduction and interpretation of vaccine deployment in the pediatric population and may indicate a need for less frequent booster vaccination in children,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Ladhani S, et al. Children develop strong and sustained cross-reactive immune responses against spike protein following SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.12.21255275, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.12.21255275v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Dowell, Alexander C., Megan S. Butler, Elizabeth Jinks, Gokhan Tut, Tara Lancaster, Panagiota Sylla, Jusnara Begum, et al. 2021. “Children Develop Robust and Sustained Cross-Reactive Spike-Specific Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” Nature Immunology 23 (1): 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-01089-8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41590-021-01089-8.