A fascinating new study discusses the 40 mutations that are seen on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein and their potential effects on viral biology.

The virus itself, which is responsible for the ongoing pandemic of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is in the same subgenus as the Sarbecoviruses SARS-CoV and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV. These are known to have originated in civets and camels, respectively, and have undergone few mutations before leaping the species barrier into humans.

In SARS-CoV, K479N and S487T were the mutations that enabled the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the viral spike to bind to the human host receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

On the other hand, they caused short though deadly outbreaks, in contrast to the SARS-CoV-2, which has already been circulating in humans for over a year. During this period, many mutations have emerged that appear to impact viral fitness, such as the D614G that rapidly became the dominant strain worldwide.

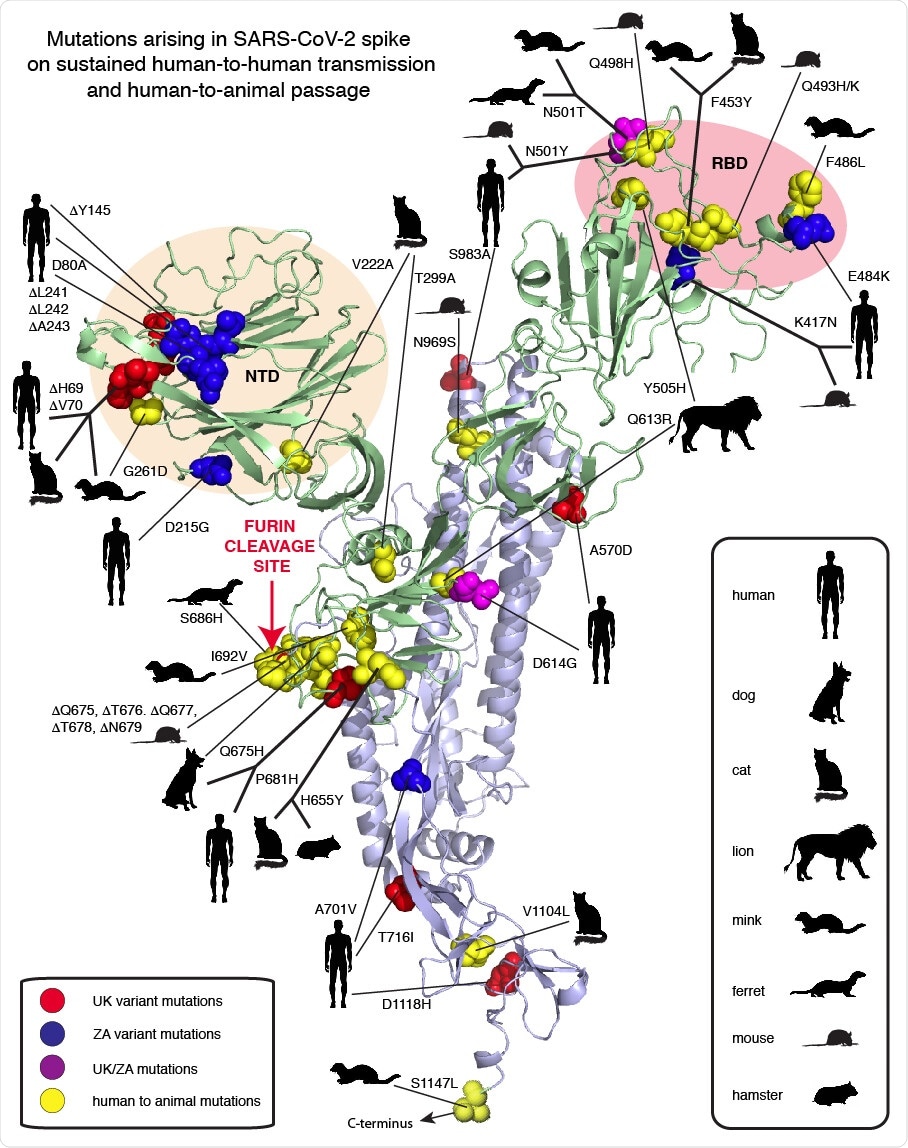

Compilation of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations occurring in humas and animals. Red spheres: United Kingdom (UK) variant, Blue spheres: South African (ZA) variant, Magenta: both UK/ZA variants, Yellow spheres: animals as indicated in the inset. NTD: Amino-terminal domain. RBD: Receptor binding domain.

This is attributed to its ability to increase the viral load in the upper airway by means of doing away with a hydrogen bond that linked this site with another on an adjacent spike protomer. By so doing, it reduced the stability of the trimeric spike, allowing greater interaction of the spike RBD with the ACE2 receptor.

The UK variant of concern, B.1.1.1.7, has 17 new mutations, with eight being located in the spike. The South African (SA) variant B.1.351 also has many spike mutations. Similarly, many mutations have been reported during the human-animal transmission of the virus, during experimental passage and during human interactions with pet or farmed, or even zoo, animals.

The Q493 and N501 residues in SARS-CoV-2 correspond to the ACE2 contact residues K479N and S487T in SARS-CoV. The UK variant shows the mutation N501Y in the second of these, as well as delH69, delV70, delY145, A570D, P681H, T716I, S982A and D1118H.

The N501Y probably allows the spike to interact with the 41Y residue on the receptor via a pi-pi bond.

The SA variant, also called 501Y.V2, has the above mutation N501Y, in addition to D80A, D215G, K417N, E484K and A701V. Another variant has been identified in Africa that has the P681H mutation, like the UK variant. This is related to the presence of the furin cleavage site in the spike protein in SARS-CoV-2.

The N501Y mutation has shown positive selection in aged mice during successive viral passages, and is associated with improved replication. When passaged still further, two mutations, namely, Q493H and K417N, with higher pathogenicity, were selected. Interestingly, the Q493K is also associated with higher replication and pathogenesis in mice, while the second mutation, K471N, is present in the SA variant.

Yet another mouse variant that emerged after six passages has been found, which contains Q493K as well as a deletion between Q675 and N679.

The transmission to mink led to the emergence of the mutations Y453F, F486L and N501T, all in the RBD, the last of which probably improves RBD-ACE2 binding. It has been observed in the virus following its passage in ferrets, which, along with mink, have given rise to two mutations at the furin cleavage site.

Transmission to pet cats and to big cats in zoos has also been reported, and dogs also can be infected. However, no mutations have been reported as essential to such species transfers.

The scientists classify the mutations into four groups:

- The RBD mutations which may allow immune evasion from existing antibodies and specific cells, or to cross a species barrier like N501Y or N501T.

- The N-terminal domain (NTD) contains the region with maximum exposure on the surface of the viral particle. This is also rife with mutations, such as delH69/delV70 in the UK variant, which, it is suggested, could improve fitness.

- Mutations in the furin cleavage site are plentiful in phylogenetic studies, and also allow the transmission to different species. The P681H in this region may affect the infectious nature of the virus.

- Multiple spike mutations such as D614G occur in the metastable spike region, and may affect infectivity. Another metastable region is at the fusion region at the base of the spike, which not only influences the transition to the fusion form, while also playing a key role as epitopes for neutralizing antibodies in other class I fusion proteins.

What are the implications?

Of the many mutations so far observed, most are relatively unimportant. Those that it is vital to keep under surveillance are N501Y, D614G and P681H, as they drive the rapid and extensive spread of the virus through the population.

Further attention should be paid, suggests an independent reviewer, to the fact that almost one in four mutations listed in this study involves a histidine residue, which has unique chemical properties making it a specific functional group at any location.

The base of the spike is less studied than its head, but has shown startlingly low changes, only one in over 125 residues so far, and none in humans. It is highly conserved, with only a 2.3% disparity from the SARS-CoV spike of the original Wuhan Hu1 virus.

The S2 base is composed of nine distinct regions which have changed little over the course of the pandemic, or even over the last century. It has several Cholesterol-Recognition Amino acid Consensus (CRAC) sequences along with a Juxtamembrane Aromatic Rich region (JAR) that partners the fusion peptide in mediating membrane fusion.

The combination of a CRAC motif followed by an especially potent JAR motif is a powerful region for cholesterol-targeted membrane perturbation. It is among the most powerful among any of the Class I Fusion Proteins, including HIV-1 and Ebola. The efficiency of the 1179-1220 region of SARS-CoV-2 as a fusion machine cannot be overestimated.”

The S2 also has a cysteine cluster at the transmembrane region that helps to anchor the large spike to the cell membrane more avidly. It provides free SH groups for intermolecular bonding.

The scientists point out that the ongoing widespread of the virus is bound to lead to the emergence of multiple non-silent mutations that affect viral spread and neutralizing capacity. Monitoring of the pandemic must therefore employ genomic sequencing all over the world.

In its absence, situations like the present are bound to perpetuate themselves, with new variants being detected long after they have left the region where they were first detected.

Moreover, to be effective against such mutants and, even more importantly, to prevent the emergence of new ones, available and newly developed monoclonal antibodies should be used in combinations, to prevent positive selection of one or more mutations by immune escape.

Finally, the number of mutations that are of biological significance is surprisingly low, and vaccination induces a robust polyclonal antibody response that cannot easily be evaded by one or other of these mutations.