Reducing the spread of COVID-19 requires vaccinating the entire population — including children. Recently, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was granted emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adolescents between the ages of 12 to 15. There’s also ongoing vaccination research for children as young as five years old. But new research published on the preprint server medRxiv* suggests the problem might not be availability but rather vaccine hesitancy.

A national online survey in March 2021 found only 49.4% of parents living in the United States were planning to vaccinate their child. A parents’ vaccination status and level of vaccine hesitancy were associated with adolescent vaccinations against COVID-19.

“We observed a strong correlation between a parent’s own vaccination status or hesitancy with hesitancy to vaccinate their child when a pediatric vaccine is available. These findings have important implications for pediatric vaccine policies and roll-out planning over the coming months,” wrote the team.

The researchers’ findings suggest that future vaccination strategies should aim to increase awareness about the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in children and its necessity to achieve herd immunity.

How they did it

A national survey in English and Spanish was offered online to parents and caregivers living in the United States with children at or less than 12 years old. Eligibility required that children received more than one medical visit in the past two years. The survey enrollment took place from March 9, 2021, to April 2, 2021.

Pediatric vaccine hesitancy rooted in concerns over safety

A total of 2,074 parents living in the United States took the survey. Of those, 49.4% said they planned to vaccinate their youngest child — the median age was 4.8 years — for COVID-19 once a vaccine was approved. In contrast, 25% said they were unsure of a pediatric vaccine, and 25.6% said they would not vaccinate.

For parents who answered as unsure or against vaccination, 78.2% cited their reason for vaccine safety and effectiveness concerns. About 23% responded that they did not find it necessary for children to be vaccinated. Other reasons to not vaccinate their children included religious (8.5%) or medical reasons (11.2%).

Other factors influencing pediatric COVID-19 vaccination

The researchers found Asian parents were 38% more likely to vaccinate their children than non-Hispanic Whites. Parents were also less likely to get vaccinated if they were female, had a high school education or less, and made less than $25,000 a year.

Getting a vaccine for their children was reported more when the parents themselves were vaccinated.

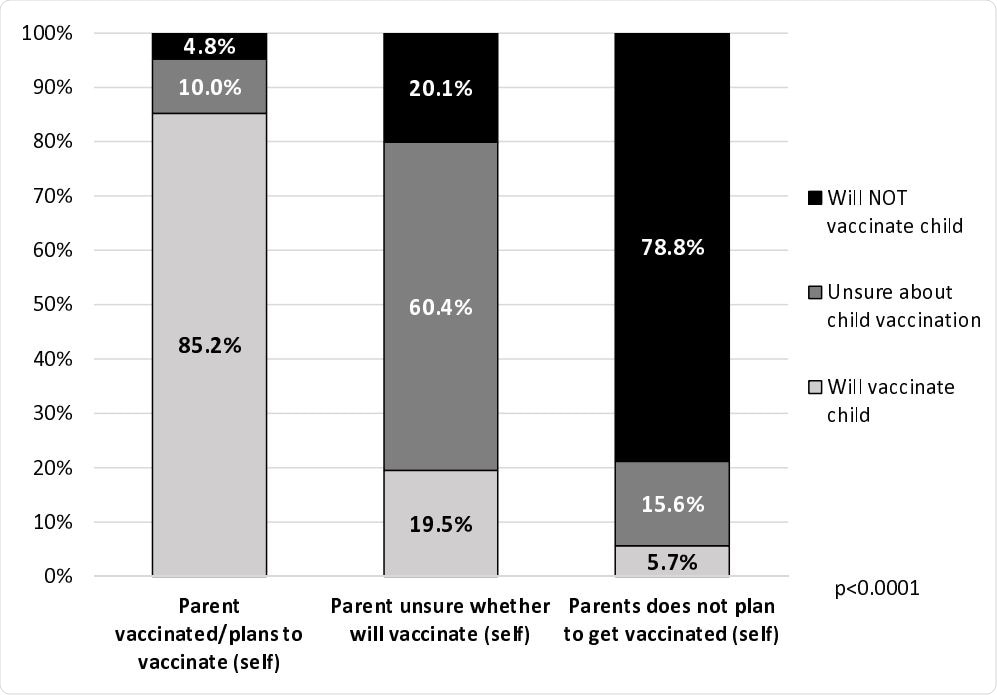

About 16.1% of parents said they were vaccinated against COVID-19, and 34.2% were planning to get the vaccine when offered. Of these, 85.2% responded that they planned to get their child vaccinated. Only 10% reported hesitancy, and 4.8% said they do not intend to get their child vaccinated.

Results showed 24.6% of parents were not sure if they would get the vaccine. Among vaccine-hesitant parents, only 19.5% said they would vaccinate their child. A majority of vaccination hesitant parents at 60.4% were unsure of vaccinated their child, and 20.1% did not plan to vaccinate.

Parental intentions to vaccinate children against COVID-19 according to parents’ own vaccination status – United States, March 9-April 2, 2021

Approximately 22.4% of parents did not plan to get vaccinated, and 2.6% of parents preferred not to answer. Parents against vaccination were less likely to get their child vaccinated.

About 78.8% of parents against vaccination said they would not vaccinate their child, and 15.6% were vaccine-hesitant. Only 5.7% of parents who said they wouldn’t get vaccinated were planning on vaccinating their child.

Given the strong correlations between parental vaccination, the researchers suggest increasing education on vaccine benefits for adults could translate to more vaccinations in children.

Study limitations

The information cannot be interpreted for children of all ages as the study targeted parents with kids 12 years and younger. The survey was also voluntarily provided and heavily relied on self-reporting, which can introduce bias in the data.

Given that reluctance to vaccinate was higher among parents with lower education and income, there is a possibility the survey was not translatable to people of lower socioeconomic status. The survey was online-only, so there is a possibility of excluding parents without internet access.

News such as the pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine could have contributed to vaccine hesitancy, but the survey was performed before the pause. There is a chance the current vaccine hesitancy in America is different from months ago.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Teasdale CA, et al. Plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19: a survey of US parents. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.12.21256874, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.12.21256874v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Teasdale, Chloe A., Luisa N. Borrell, Spencer Kimball, Michael L. Rinke, Madhura Rane, Sasha A. Fleary, and Denis Nash. 2021. “Plans to Vaccinate Children for Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Survey of United States Parents.” The Journal of Pediatrics 237 (October): 292–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.021. https://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(21)00688-0/fulltext.