A team of scientists from the Washington University, in St. Louis, USA, has recently conducted a survey to analyze factors responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination hesitancy among US citizens. The study findings reveal that public willingness to vaccination can likely be improved by allowing them to select vaccine brands and locations. In contrast, vaccine mandates can further increase public aversion toward vaccination. The study is currently available on the medRxiv* preprint server.

The recent outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative pathogen of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has put a significant burden on the global healthcare system because of high viral infectivity and disease severity. Even though there have been numerous advancements in vaccine science, the mass vaccination programs in many countries face a serious challenge due to public skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Since COVID-19 vaccines have been developed rapidly, there is an increasing public hesitancy toward vaccine safety and efficacy. A significant proportion of the general population is even unconvinced about the actual severity of COVID-19.

In the current study, the scientists have explored strategies to increase vaccination rates among the general population in the US. They have specifically aimed to identify factors associated with public hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination.

Study participants

The study was conducted on 2,895 US citizens (age range: 33 – 62 years) between March 15 and March 22, 2021. Of all participants, 38% were already vaccinated, 41% reported strong willingness for vaccination, 28% reported relatively less willingness for vaccination, 18% reported unwillingness for vaccination, and 10% reported strong unwillingness for vaccination.

As reported by the participants with strong willingness for vaccines, the main reasons for not getting vaccinated include difficulty securing vaccine appointments, lack of information on vaccine location, and distance of vaccination centers.

Regarding vaccine hesitancy or strong unwillingness, participant-reported reasons were vaccine safety and efficacy related concerns, mistrust in government policies, and disbelieve that COVD-19 is a serious disease.

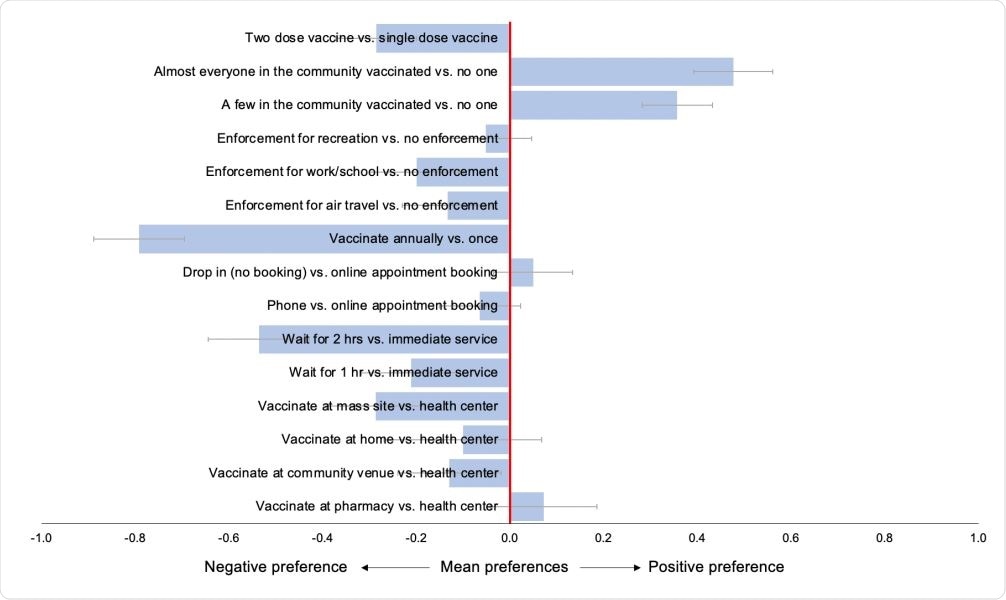

Weighted mean preferences (relative utilities) for vaccination campaign features, in total population (N=2,985)

Public preferences for vaccination

Regarding preference for COVID-19 vaccination centers, the study participants showed equal willingness for pharmacies and home compared to health facilities. A slightly negative preference was reported for community venues, and a strong negative preference was reported for mass vaccination sites supported by the national guard.

Compared to the long waiting time (1 or 2 hours), an immediate service was preferred by the participants. Compared to scheduling appointments online, an equal preference was reported for telephonic and drop-in appointments.

Among participants, a constant negative preference was observed for vaccine enforcement measures taken for air travel, workplace/school attendance, and group recreational activities. Moreover, an inverse correlation was observed between vaccine hesitancy and willingness to vaccinate under enforcement.

Regarding vaccination regimen, the participants reported less preference for two-dose vaccination compared to single-dose vaccination. In this context, the strongest negative preference was reported for annual vaccination programs compared to a single vaccine episode with long-lasting protection.

In participants with strong negative responses for vaccination, no influence of community vaccine coverage was observed on decisions toward vaccination. In contrast, a positive influence of community vaccine coverage on vaccine-related decision-making was observed among participants who showed relatively less hesitancy for getting or not getting vaccinated.

Population subgroups based on vaccine preference

Based on vaccine preferences, six subgroups were identified. About 8% of participants belonging to the “single-dose” group, 15% of participants belonging to the “two-dose” group, and 22% of participants belonging to the “vaccine once” group showed strong negative preferences for two-dose vaccination, single-dose vaccination, and annual vaccination, respectively.

About 9% of participants belonging to the fourth group showed strong preferences for immediate service rather than long waiting time (1 or 2 hours) at vaccination centers. In addition, about 13% of participants belonging to the “social proof” group reported that their willingness for vaccination would increase if at least few persons from their community are vaccinated first.

About 32% of participants belonging to the “control averse” group showed strong and consistent negative preference for vaccine enforcement. Vaccine enforcement was found to be the major determinant of vaccine hesitancy and aversion, especially among young individuals, Black/African Americans, and Republicans.

Study significance

According to the study results, promoting voluntary vaccination and offering a choice of brands and locations could increase public preference for COVID-19 vaccination.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources