The global coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a momentous effect on society, with public health notices from the government encouraging adults to work from home and schools shifting to online learning platforms to teach their students. As lockdown has eased in many countries around the world, schools and workplaces have similarly returned to their normal setting.

Many workplaces look different now as compared to before lockdowns were first initiated due to the presence of masks and rigorous testing requirements for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Much of the testing that is conducted in these settings include lateral flow tests that are followed by a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) RT-PCR test, if necessary.

The mass use of rapid lateral flow tests, which has been supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), has enabled some semblance of normality at both work and school. The benefits of using lateral flow devices (LFDs) include their low costs and ease of use.

Throughout the United Kingdom, LFDs have been used by schools since March of 2021. These schools often utilize these devices to test students twice weekly with the aim of preventing the spread of infection in the event that a student(s) tests positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Despite their utility, there has been considerable controversy surrounding the use of LFDs, as some students have reported that the application of soft drinks instead of their own sample can result in a positive test. To that end, a group of collaborating researchers from Liverpool systematically tested a variety of different soft drinks to determine their ability to create false-positive results.

LFDs and SARS-CoV-2

LFDs are designed as cartridges that comprise a nitrocellulose membrane strip and absorbent paper that contains dried test reagents. When these reagents are mixed with the analyte from a test sample, they migrate through the nitrocellulose strip and over the test line where the SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody is fixed.

Two lines can be produced in a lateral flow test. One line is the control line that confirms that the test is functioning properly and its validity, whereas the other line is produced if the sample tests positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The Innova SARS-CoV-2 antigen rapid qualitative test was one of the first devices that completed the multi-stage evaluation process. As a result, this test was used in pilot testing in communities within Liverpool.

LFDs have been used for large-scale community open-access testing due to their ability to accurately distinguish between individuals who are presenting with a higher viral load of SARS-CoV-2. While RT-PCR tests are more sensitive to the virus than lateral flow tests, the widespread availability of LFDs is generally much better than that of RT-PCR tests.

Additionally, LFDs only require about 30 minutes to provide test results, which is comparable to the 48 hours needed to obtain RT-PCR results. This is a significant advantage, as it can allow individuals who test positive to remain in their house to isolate and prevent the spread of the infectious virus while they follow-up with an RT-PCR test.

Rapid testing in schools

With schools reopening on March 8, 2021, LFDs were introduced for rapid asymptomatic testing in secondary schools to allow for students and staff to be tested for SARS-CoV-2 twice weekly. Those who had tested positive through these tests were made to isolate, along with individuals who had been in close contact with them. A subsequent RT-PCR test was to be booked for these individuals within 48 hours of receiving the positive result.

However, after three months of regular testing, a school in Merseyside had reports of students who had found that either drinking fruit-flavored juice or misusing them as an analyte had the potential to provide a false-positive result. To that end, Liverpool-based researchers have undertaken a study to evaluate a variety of soft drinks and determine their ability to be misused as an analyte and provide a false-positive result for SARS-CoV-2.

False-positive tests

The team had investigated 14 brands of common non-alcoholic soft drinks, consisting of:

- Highlands Spring Water

- Robinsons Hydro Fruit Shoot Blackcurrant Spring Water

- Robinsons Fruit Shoot Blackcurrant and Apple

- Robinsons Fruit Shoot Orange

- Robinsons Fruit Shoot Apple

- Coca-Cola

- Diet Coca-Cola

- Sprite

- Fanta

- Appletiser

- Blackcurrant Concentrated Juice

- Pineapple Concentrated Juice

- Orange Concentrated Juice

- Apple Concentrated Juice.

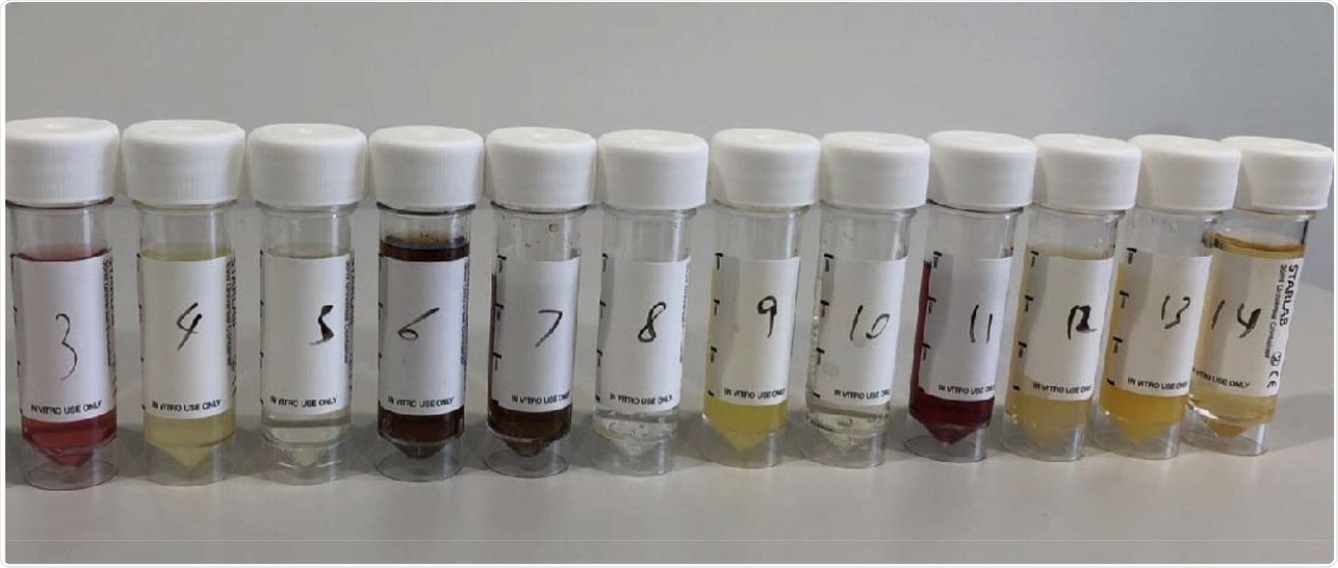

The 14 soft drinks that were included in this study in the original packaging (a) and sterile universal containers (b).

The 14 soft drinks that were included in this study in the original packaging (a) and sterile universal containers (b).

Each of the drink samples was allowed to stand for two hours before analysis to allow for them to reach room temperature. One milliliter (ml) of each sample was then drawn into the extractor tube of the Innova kit. The sugar quantity and ingredients of each sample were also noted. The acidity was also tested using a urinalysis strip which included pH quantification.

In addition to these drinks, four sweeteners were also tested, which included Splenda, Canderel, Sweetex, and Hubbard’s Foodstore. To prepare the sweeteners, the researchers dissolved one tablet of the sweetener into 20 ml of spring water, of which 1 ml was used for actual testing.

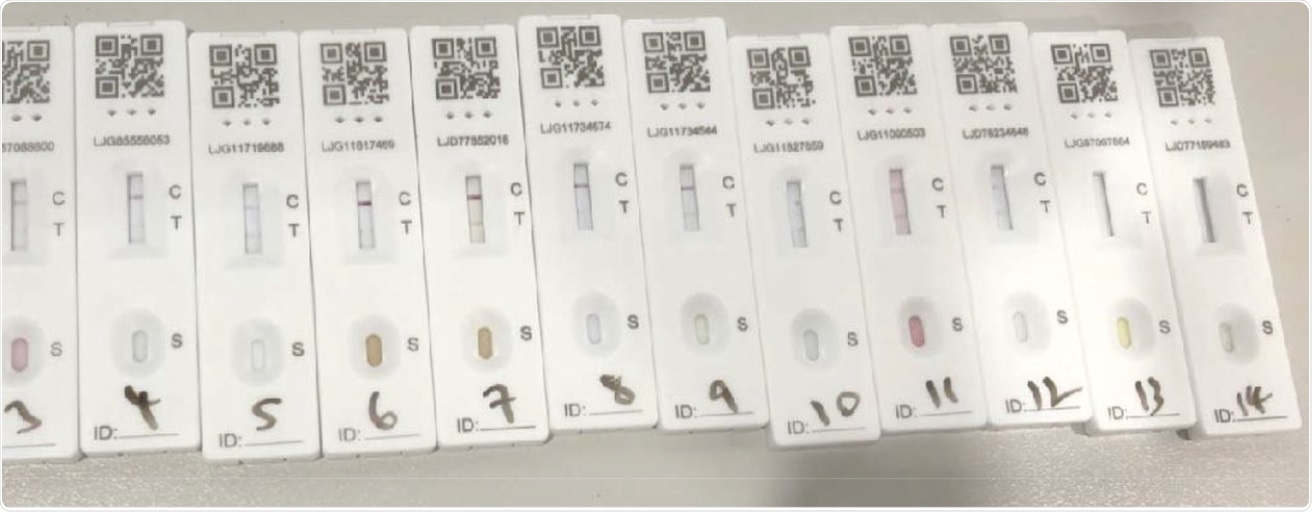

The SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow device results following administration of the 14 soft-drink specimens.

The SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow device results following administration of the 14 soft-drink specimens.

Study results

Mixed findings were reported in this study, with spring water having a definite negative result, 3 out of 14 drink samples producing void LFD results which mainly included drinks from fruit concentrate, and 10 out of 14 drinks producing a positive test result. The researchers found that the drink samples that produced false-positive test results were all similar in their sugar and pH levels. Additionally, all four sweeteners that were included in this study resulted in negative LFD tests.

The researchers concluded that, in line with the user guide provided, food and drinks should not be consumed 30 minutes prior to taking the test. They recommended that the test be performed in the morning and with possible supervision.

The actual mechanism of the false positives that were identified in this study remains unclear and will therefore require further research and analysis, as the acidity and sugar content of the drinks did not appear to have any effect on the results. The researchers suggest that future studies evaluate the preservatives present in these drinks in order to determine their role in contributing to the occurrence of these false positives.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.