Within the United States, health infrastructural challenges combined with the biological characteristics of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have limited the ability of this nation to effectively control the spread of this virus. Another major obstacle that has prevented the proper handling of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the United States has been contradictory messaging from scientists, the government, and the media, whether via print or online journals and newspapers, and social media.

Study: COVID-19 Related Messaging, Beliefs, Information Sources, And Mitigation Behaviors in Virginia: A Cross-Sectional Survey in The Summer Of 2020. Image Credit: Kits Pix / Shutterstock.com

Study: COVID-19 Related Messaging, Beliefs, Information Sources, And Mitigation Behaviors in Virginia: A Cross-Sectional Survey in The Summer Of 2020. Image Credit: Kits Pix / Shutterstock.com

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Background

Along with daily bulletins by highly qualified and responsible public health professionals, conspiracy theories and misinformation, which were largely driven by social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, have spread like wildfire throughout the U.S. The outcome was growing disbelief in the government and its interventions/messaging, as well as those of public health authorities.

The chronic saga of unequal treatment and opportunities for Blacks and other ethnic minorities exacerbated these issues as evidenced by the long-standing shortage of funds for health agencies at state and federal levels. As a result, Blacks, Indigenous, and Hispanic groups, who have had less access to public health plans and medical care for several decades, have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic. These disproportionate effects on these communities have been further intensified due to the higher percentage of poor, less-educated, and elderly people in these populations, all of which are high-risk factors for COVID-19-related disease and death.

Taken together, these disparities demonstrate how essential it is for a public health strategy to be sensitive to these factors. Furthermore, it is also imperative to build trust in these communities to educate and effectively implement preventive and containment measures that can reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Importantly, earlier research indicates that despite all the noise on social media platforms, a major chunk of the population, including the above high-risk groups, continues to trust the government and public health officials, and/or their doctors, on messaging aimed at helping them protect themselves and others from the virus.

“Demonstrating that public health measures and preventative strategies are in the best interests of the community overall is crucial to building and maintaining public trust that is essential to effective public health guidance.”

Virginia has also shown regional variations in caseloads over the period of the pandemic. The northern and central regions of the state have had large increases in cases early on, with the rest of the state, which is largely rural, having a delayed introduction to the virus. College towns also experienced a local surge once students returned for the fall semester, despite their low population densities.

About the study

Using survey methods, the researchers collected information on sociodemographics, political affiliation, beliefs about COVID-19, as well as information sources that the respondents felt were credible.

Between May 19 to July 19, 2020, the researchers obtained approximately 3,500 responses from all over the state of Virginia. The largest number of responses was from Montgomery County, Loudoun and Fairfax Counties, as well as Wise County.

Almost 80% of the respondents were women, and a slightly higher percentage were Whites. The vast majority had some college or higher education. About 67% had an annual household income above $60,000, with 43% having an income of $100,000 or more. About half were Democrats, and 13% were Republican by political affiliation.

Trusted information sources

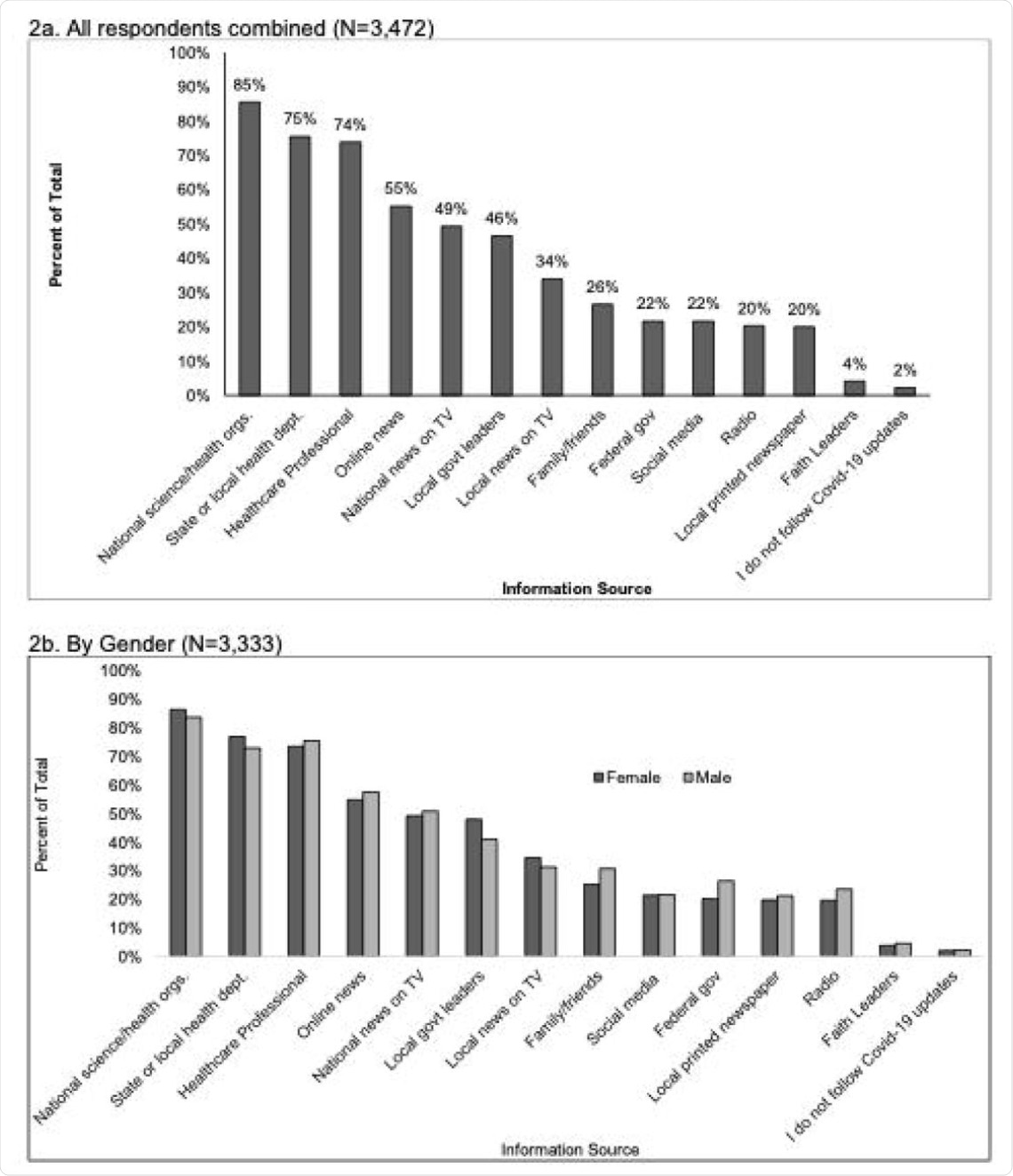

Most of the responses (85%) indicated that science and health organizations were trusted sources of information on the pandemic, with 75% also indicating that they relied on their local and state health departments, as well as their doctors. Just over half used online sources.

Approximately a quarter of respondents said they trusted their family and friends for pandemic-related information. Comparatively, 34% of respondents depended on local television news, whereas 49% relied on national television news. 46% of respondents indicated that they listened to their local government leaders, while 22% trusted national government, social media, or newspapers.

While more women tended to believe local officials and health departments, more men received their trusted information from family, friends, or national leaders.

Family and friends were more important sources for people between the ages of 18-24 as compared to all other age groups overall, at 39% and 25%, respectively. 31% of respondents between the ages of 18 and 24 believed in social media, whereas 21% of all other age groups relied on social media for their information on the pandemic. Additionally, 18-24-year-olds were less likely to rely on printed news, radio, and local leaders as compared to older age groups.

Survey responses to the question: “Where do you get information that you trust about coronavirus/COVID-19? (Check all that apply)” for all respondents (2a), and by gender (2b), age-group (2c), race/ethnicity (2d), political identity (2e), education level (2f), income level (2g), and Virginia region (2h).

Survey responses to the question: “Where do you get information that you trust about coronavirus/COVID-19? (Check all that apply)” for all respondents (2a), and by gender (2b), age-group (2c), race/ethnicity (2d), political identity (2e), education level (2f), income level (2g), and Virginia region (2h).

Over 80%, both Whites and others, trusted national science organizations and public health institutions. Whites and non-Whites differed in trusting printed newspapers, local television and social media, by 6% to 12% only.

Democrats and Republicans differed by 10% to 20% in their trust in state or local health departments, science and health organizations, newspapers, radio, and local leaders. Taken together, Democrats generally showing more trust in all of these information sources. An exception was with federal leaders, where Republicans were more likely to trust them, at 46% versus 13%, respectively.

Education-wise, individuals with lower education tended to promote reliance on faith leaders, local television, and federal leaders, as did those of a lower income bracket.

Beliefs about COVID-19

While up to a third expressed worry about getting sick, especially with severe disease, approximately 80% thought it was a serious problem. Significantly, 85% of women and college-educated people, as compared to 77% of men and those with lower education, shared this perception.

About 95% of Democrats and 60% of Republicans felt COVID-19 was a serious threat, as did 90% of those over the age of 60 and 80% of those younger than 60. Finally, 91% of Asians and 84% of multiracial and Whites perceived COVID-19 as serious, with Blacks and Hispanics coming in between.

Up to a third, more women than men said this perception came from hearing news of the pandemic from other countries or states, or mandatory restrictions and closures. Less than half traced this feeling to knowing someone who became sick, being themselves, or living with someone at risk for severe COVID-19.

Whites and non-Whites cited these reasons in similar measure, with differences of 10% or less – except for knowing someone who fell sick. This reason was cited by almost half the non-White participants as compared to less than 30% of Whites.

Again, Democrats and Republicans differed by 10% on most reasons, except for a governor’s declaration of a state of emergency (80% vs. 45%), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) face mask recommendation at 76% vs. 53%, COVID-19 news from other countries (86% vs. 56%), or states (80% vs. 60%).

People with a higher education/higher income tended to think of the situation as serious because of a declared state of emergency, work-from-home, face mask recommendations, or hearing about COVID-19 from another country or state. Less-educated/lower-income people were more often impacted by personal COVID-19 or a high-risk state, limited purchases at stores, and the online nature of religious services.

Messaging

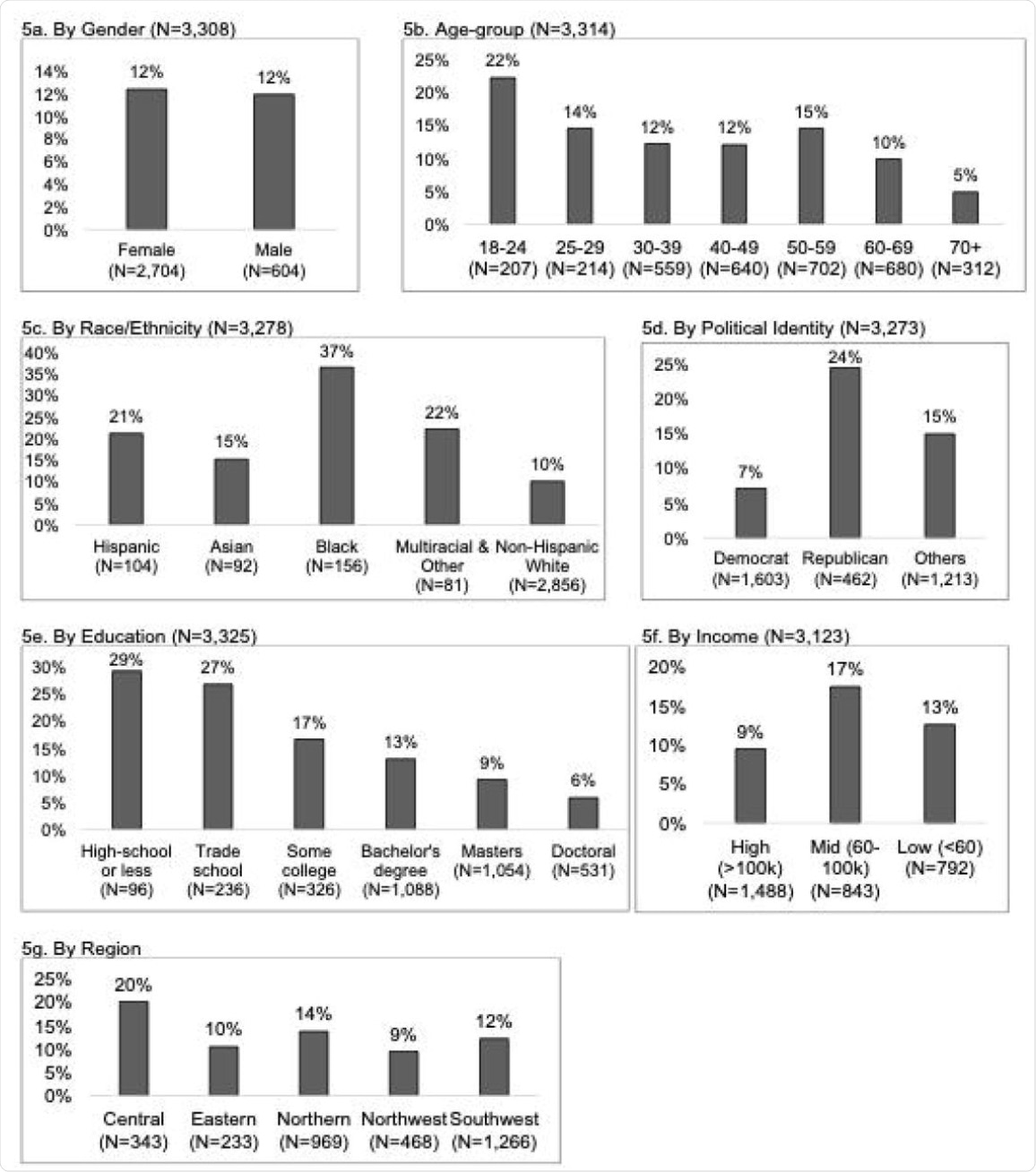

While 80% believed the evidence-based messaging about COVID-19, just over a tenth believed various other hoax or conspiracy-based messages. Lower education, younger age, non-White origin (except Asians), and Republican affiliation predicted a tendency to believe these alternative messages, as did a higher income level and residence in central Virginia.

People who believed an alternative message were also more likely to trust information from family and friends, national officials, social media, and local television. Comparatively, those who did not believe these conspiracy theories had a 10% higher chance of believing health officials or newspapers, online news or radio, as well as science and health organizations.

Percent of respondents who selected they believed in one or more alternative message when answering the question: “The following messages are related to the coronavirus/COVID-19 (not all are true). Please check all that apply if you have heard, believe, and/or changed your behavior based on each message” by gender (5a), age-group (5b), race/ethnicity (5c), political identity (5d), education level (5e), income level (5f), and Virginia region (5g). Alternative messages response options include: COVID-19 “was developed as a bioweapon,” “was developed to lower social security payments to seniors,” “is a sign of the apocalypse/end times,” “is a hoax,” “can be treated with natural remedies,” “was developed for population control,” and “was developed to increase sales of cleaning supplies.”

Percent of respondents who selected they believed in one or more alternative message when answering the question: “The following messages are related to the coronavirus/COVID-19 (not all are true). Please check all that apply if you have heard, believe, and/or changed your behavior based on each message” by gender (5a), age-group (5b), race/ethnicity (5c), political identity (5d), education level (5e), income level (5f), and Virginia region (5g). Alternative messages response options include: COVID-19 “was developed as a bioweapon,” “was developed to lower social security payments to seniors,” “is a sign of the apocalypse/end times,” “is a hoax,” “can be treated with natural remedies,” “was developed for population control,” and “was developed to increase sales of cleaning supplies.”

Behaviors

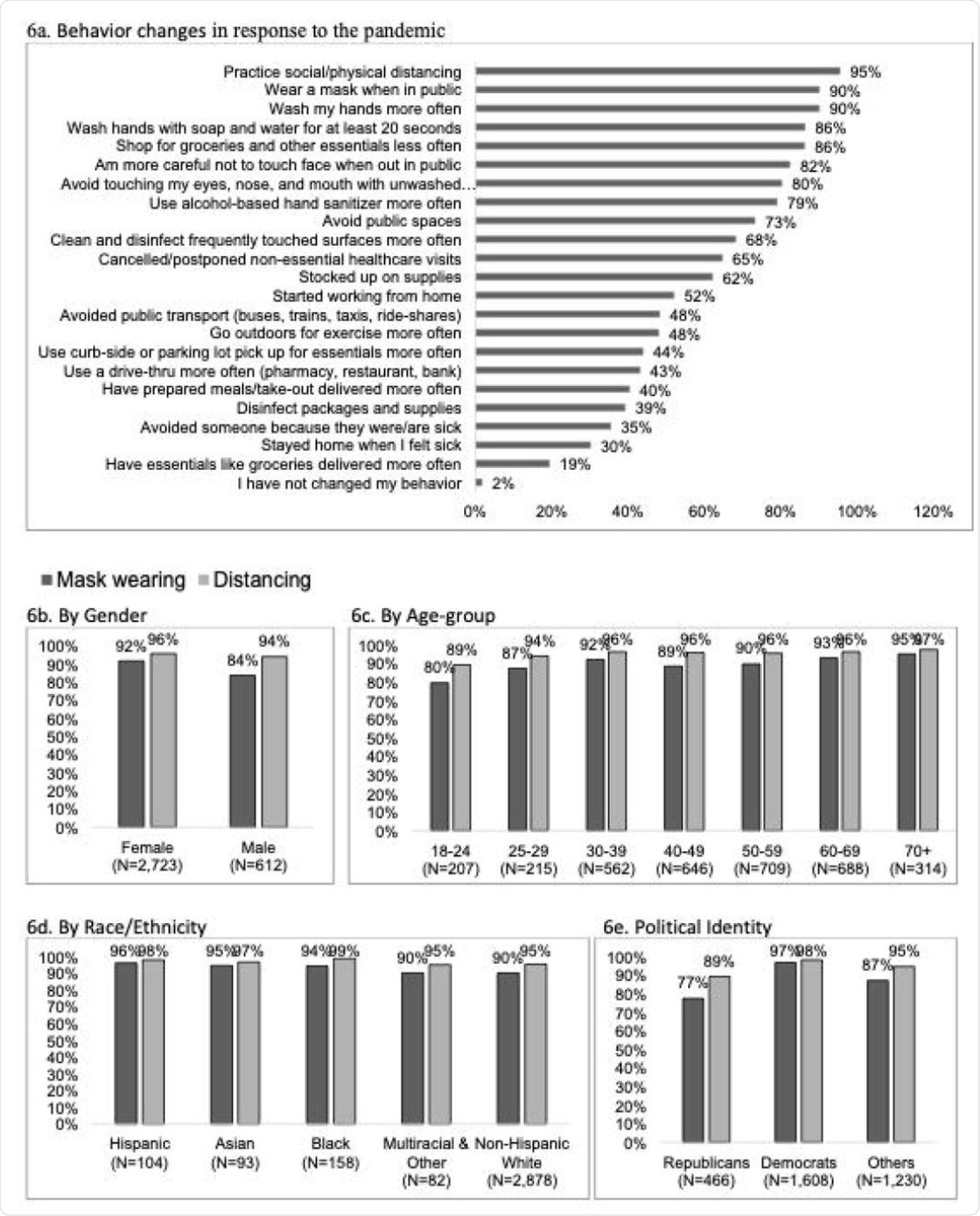

Almost all respondents said they had changed their behaviors in one or more ways, such as physical distancing, masking in public, masking, and handwashing. A significant majority also said they were restricting shopping trips and avoiding public spaces, while half said they were working from home.

When assessed by group, these measures were adopted by more women than men, and by older people, almost all Democrats and highly educated people, as well as those with higher incomes.

The trends with mask-wearing also followed earlier patterns of trusting evidence-based messaging. Republicans had five-fold higher chances of not wearing a mask in public, while Southwest Virginians, young adults, and those of lower education levels were all associated with twice the odds. Those who believed alternative messages and did not trust science or health organizations had three and two times the risk of not wearing a mask, respectively.

Survey responses to the question: “How (if at all) have you changed your behavior in response to the coronavirus/COVID-19? (Check all that apply)” for all respondents (6a). Percent of respondents reporting mask wearing and distancing by gender (6b), age-group (6c), race/ethnicity (6d), political identity (6e), education level (6f), income level (6g), and Virginia region (6h). Percent of respondents reporting an information source as trustworthy by if they reported wearing or not wearing a mask in public (6i) and by distancing or not distancing in public (6j).

Survey responses to the question: “How (if at all) have you changed your behavior in response to the coronavirus/COVID-19? (Check all that apply)” for all respondents (6a). Percent of respondents reporting mask wearing and distancing by gender (6b), age-group (6c), race/ethnicity (6d), political identity (6e), education level (6f), income level (6g), and Virginia region (6h). Percent of respondents reporting an information source as trustworthy by if they reported wearing or not wearing a mask in public (6i) and by distancing or not distancing in public (6j).

Implications

The study shows close correlations between what sources of information people trust, what they believe, and how they changed their behaviors after the onset of the pandemic. Social and demographic factors, ethnicity, political affiliation, and even geographical location, all contributed to how these survey responses were filled out.

“Respondents who identified as non-Hispanic White, men, Republican, other political identity, younger age, income <$100,000, did not report national science and health organizations as a trusted source, reported believing an alternative message, and/or living in Southwest Virginia had greater odds of not wearing a mask.”

Other research corroborates these trends, with older people being more anxious about the pandemic but less so about the economic and social issues caused by the virus and containment measures. Misinformation was higher among younger people, minority groups, those with lower education levels and socioeconomic status, and politically conservative people.

“This study can assist decision makers and the public in developing more effective public health messaging for both the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and for future public health challenges in Virginia and similar settings in the United States.”

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.