Therapies should be highly effective and as free as possible of side effects—a big challenge, particularly in the case of cancer. A Chinese research team has now developed a novel form of photodynamic tumor therapy for the treatment of deep tumors that works without external irradiation. The light source is built into the drug and is “switched on” selectively in the microenvironment of tumors, as they report in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

Image Credit: Angewandte Chemie

Classic photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive cancer treatment that is relatively gentle because of its specific spatial and temporal selectivity. To start with, a photosensitizer is administered, then the region where the tumor is located is irradiated with light. The photosensitizer is excited by the light and transfers some of the absorbed energy to oxygen molecules, resulting in reactive oxygen species that destroy tumor cells. Because of the limited depth of penetration of the necessary visible or UV light in tissues, this method is only useful for shallow tumors.

A team led by Xiaolian Sun (China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing) and Guoqiang Shao (Nanjing Medical University) has now developed a new photodynamic tumor therapy that works for deep tumors. It does not need external irradiation because the photosensitizer brings its own “lamp” along and “switches it on” on its own once it reaches the tumor.

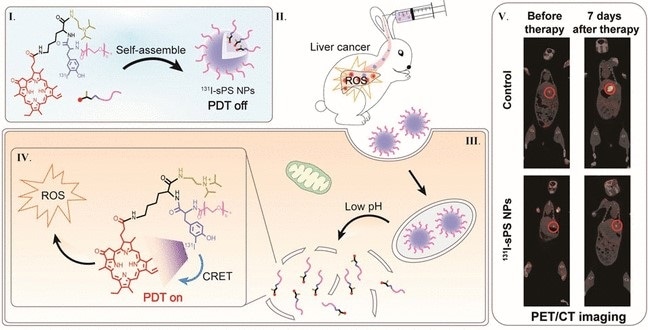

This “intelligent” drug consists of four components linked into a single molecule: a photosensitizer (pyropheophorbide-a), a pH sensor (diisopropylamino group), a polymer (polyethylene glycol), and the “lamp” (the amino acid tyrosine carrying a radioactive iodine-131 isotope). At the pH values found in healthy tissues, the molecules are tightly aggregated into nanoparticles. In this compact form, the “irradiation” is switched off (quenched) and the drug has no effect. However, tumorous tissue has a somewhat more acidic pH value. This environment causes the pH sensor to change structure, and the nanoparticles fall apart—the irradiation is switched on, and reactive oxygen species are formed that kill the tumor cells.

How does this “built-in light” work? As it decays, the radioactive iodine isotope I-131 releases β-radiation (electrons) and γ-radiation. As the electrons move, their charges polarize atoms, thereby causing dipole oscillations that send out electromagnetic waves, which means light. Usually, these waves cancel one another immediately. Yet, in the dense aqueous environment of the cells (other than in vacuo), the electrons sent out by I-131 are faster than light. In this case, the quenching of the waves is incomplete, resulting in a bluish light known as Cherenkov radiation. This excites the photosensitizers enough to destroy tumor cells. In cell cultures and animal models, the new drug demonstrated powerful tumor inhibition with low toxicity and minimal side effects on healthy tissue.

Source:

Journal reference:

Guo, J., et al. (2021) Smart 131I-Labeled Self-Illuminating Photosensitizers for Deep Tumor Therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. doi.org/10.1002/anie.202107231.